Beyond the White Clouds

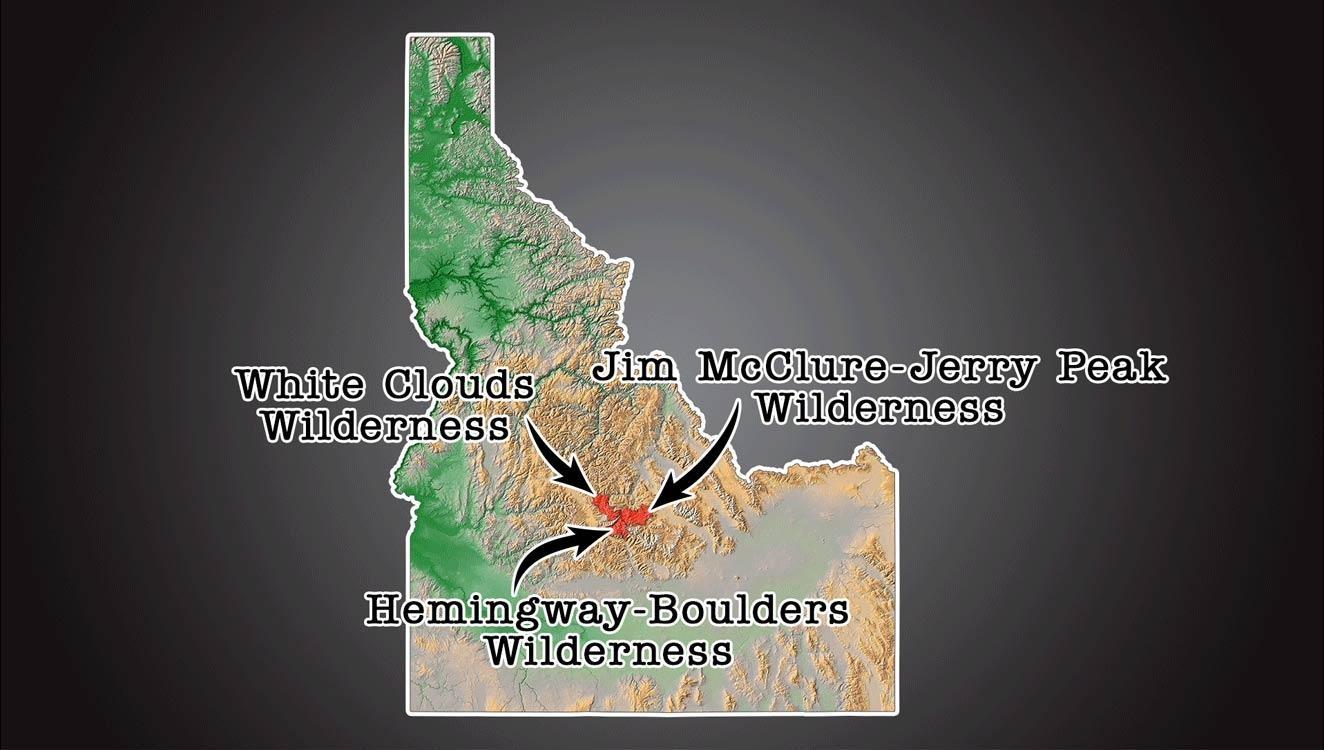

It’s some of the most dazzlingly diverse country in the West, deserving of the gold standard of protection. In this hour-long special, the Outdoor Idaho crew visits the three new wilderness areas in the center of Idaho—the White Clouds, the Hemingway-Boulders and the Jim McClure-Jerry Peak Wilderness—to tell the fascinating fifty-year story of how the threat of an open-pit molybdenum mine eventually led to a unanimous vote for wilderness in Congress. This program also examines some of the major battles yet to be decided.

Personal Essays

Summer was going by way too fast. Our week long backpacking trip to Chamberlain Basin in the White Clouds wasn't going to happen this summer, but we did have time for a day-hike.

Years ago, I had ridden horse back to Champion Lakes. It was only an overnight trip, but I remembered how beautiful it was and how good those lake trout tasted. Fast forward to just six years ago, I accompanied a group of ladies on day hikes to 4th of July Lake and Washington Lakes and was reminded of what I'd been missing those years in between my last visit. Since then, I've been back with friends for more exploring and enjoying this amazing area that doesn't get as many visitors as its more famous neighbor, the Sawtooth Mountains.

A brother of mine and I hadn't spent much time together since we graduated from high school over forty years ago. His career took him to places far away from where we grew up. So, what better way to visit and get reacquainted than to go spend some time in the newly declared Boulder-White Cloud Wilderness Area? He'd heard my stories hiking to 4th of July Lake, Washington Lake and over into Antz Basin, so we chose that hike in lieu of our extended backpacking trip to Chamberlain Basin. His oldest son, who has his doctorate in geology, accompanied us on our trip.

All my stories of how magnificent the White Clouds were, did not prepare either one of them for the stunning views and vista that we saw. My nephew was totally intrigued with rock formations and when asked, gave us a little insight to geological processes that might have happened during the past several million years.

Upon reaching the saddle of Antz Basin on our return trip, we paused at the sign that told of the newly established wilderness area and were grateful that the area is protected and will remain much as it is today for generations to come. Next year, Chamberlain Basin.

How I envy Lewis and Clark and the many great explorers of “The West” -- John Colter, Jim Bridger, Kit Carson, to name a few. How I so wish I could have seen what they saw over two hundred years ago. Land that was virtually untouched and well preserved, thanks to the native tribes who were great stewards of the land. With great visionaries such as Teddy Roosevelt and important naturalists such as John Muir, we have continued on a path to preserve our precious resources. If it wasn’t for William Henry Jackson’s photographs and Thomas Moran’s paintings of Yellowstone, Ulysses S Grant may not have set aside Yellowstone as a national park. In more modern times it was Ansel Adams who brought National Parks into our homes with his stunning photographs. His persistence in environmental preservation and the creation of the Sierra Club set off a wave to preserve some of the best known landscapes in the West.

Today we continue to set aside lands that will be preserved for the enjoyment of many who will follow us. Just as there was considerable opposition to the creation of national parks, there is an opposition against the creation of “Wilderness” areas. Personally, I am grateful for those who felt so strongly about preservation that they dedicated their entire lives to the cause. I derive some of my greatest pleasures by visiting these special places time and time again. With the creation of the Boulder White Clouds Wilderness we have preserved some of Idaho’s most beautiful country for years to come.

Just this past summer I was fortunate to join the crew of Outdoor Idaho in Hemingway-Boulders Wilderness as they were filming their upcoming episode of “Beyond the White Clouds.” One of our main objectives was to summit Ryan Peak in the heart of the Wilderness. As we stood at the saddle, well below the summit, all nine of us came up with the consensus that there was no consensus on how to get to the top. A few chose to chase after a solitary mountain goat for a photo opportunity, and the others, well let’s just say they headed off on their own path, like the explorers of the past. Eventually we all made it to the summit with a tale to tell. As I stood on the summit of Ryan Peak, the second highest peak in the Boulder White Clouds Wilderness, only one hundred feet lower than the majestic Castle Peak, I gazed out over the vast Wilderness for several minutes. It was only then that I realized that I no longer needed to be envious of the early explorers, for the view I was seeing was exactly the same view they witnessed two hundred years ago.

The designation of the Boulder-White Clouds as Wilderness cuts deeply. It means loss because it has been taken away for what could be forever. The area, newly off limits to many user groups, was already mostly protected from development. Looking back at my own photos from 2015, listening to “old-timers” stories and seeing vintage video reminds me how lucky I was to have had the opportunity to criss-cross the area, from Bowery Guard station over Castle Divide and back under my own power in one day, on my bicycle. The ride from 4th of July through Antz Basin across the breathtaking meadows of Martin Creek to end at the bottom of Big Casino to soak for a few minutes in the Salmon.

The backcountry trail systems are in constant need of maintenance, the wind-blown snags are so many in number they are hard to keep up with using modern tools and motorcycles. The hikers now have what they wanted, it is only open to them. I do hope they can keep up with the system, but I fear they will not. As with other Wilderness areas I’ve spent time in around Idaho, Montana and Oregon I suspect the trails become more and more overgrown. Detours around the multitude of snags will cause damage to native vegetation, erosion will win out where it can and the Earth will reclaim the land. The weekend prior to signing I was lucky enough to cover terrain that only the most determined riders can navigate, sometimes carrying my bicycle. I hope that one day I can ride some of this great backcountry area with my kids and that other user groups will regain access to portions of this lost gem.

Idaho is full of amazing wilderness terrain, so why are the White Clouds so special? Rugged peaks, alpine lakes, and wildflower filled meadows can be found in several Idaho mountain ranges. But there’s just something about the White Clouds that takes that combination to a totally different level. To me there is no better place to go hiking, backpacking, or mountain climbing.

The White Clouds are home to the densest population of alpine lakes in Idaho. No other range in the state has even close to as many lakes above 9,000’ in elevation. If you take these above-treeline lakes, surround them with rugged peaks composed of highly reflective rock, you are left with a combination that creates almost indescribable sunrises and sunsets. To me a combination like this is no accident. It is a setting that gives perspective and appreciation for the intricate design that we are just a small part of.

I’m an Idaho native, born and raised. And somehow, even with the Idaho backcountry as a constant presence in my life, I didn’t venture into the White Clouds for the first time until I was almost 30 years old. But ever since that first trip, I’ve been a total White Cloud addict. There’s just something about being in amongst those big pale peaks that is incredibly therapeutic for a desk jockey like me. Over the past 14 years I’ve been blessed to cover over 400 miles on foot and summit over 60 mountains in this amazingly addictive mountain range. And now thanks to the wilderness designation, I rest easy knowing the area will be preserved for future generations to discover their own White Cloud addiction.

My family and I enjoy backpacking trips into this country where we escape the everyday stresses of the city to enjoy spectacular breathtaking beauty and serenity only found in such places. When I come back to my work and family I'm rejuvenated, more appreciative and grounded in what is really important to me. Keeping up with the Joneses loses its space in my mind while I'm within these incredible places. Knowing that there are places protected from commercial development and natural resource extraction brings happiness to me. Knowing there is an additional 275,000 acres of habitat and intact ecosystem protected for future generations is important to me. To me, the Boulder-White Clouds is a sacred place and even if I was not to utilize it just knowing it exists and is a protected, wild place is important to me.

I had only been in Idaho for about 2 ½ years. I was pretty sure I had made the right decision to take a job with IDFG and live the rest of my life in Idaho.

Late October found a group of us making an elk and deer hunting trip back in to the East fork of the Salmon River. We were going to spend two or three days "back in" looking for some meat for the freezer and maybe some good antlers.

Even before we got to the camp we saw whitetails --not Iowa, corn fed whitetails, but whitetails nonetheless. A few more miles up the East fork brought Mule deer into view out in the sagebrush hills. Near the Baker place, a small herd of antelope tried to play chicken with the truck. Later that morning a small bull and cow moose walked across the creek above camp. Nearer to lunch a large black bear decided to watch us from across the East fork near Baker creek while we unpacked our food. So, what is that, five species of big game before 1:00 pm?

"There are some sheep!" Phil said.

"There's a good billy on that steep face below the summit on Sheep Mountain!" Todd said.

"Is that a herd of elk on the edge of that finger of timber?!" I asked.

"Yep." said Todd. "And that bigger bull will go about 380; he is huge!"

As we pulled into camp next to the East fork of the Salmon River, a rarely seen resident padded across the lane and into our headlights. My second such sighting. A very unhurried and very large cat was lit up by the hi-beams and was gone.

The night we returned home, I called my Dad back in Iowa. I had only been away from the Cyclone State for less than three years.

"How was your trip?" my Dad asked."Dad, I saw NINE species of big game in one day!”

"Is that a lot?" he asked.

“Dad, I am never coming back.”

The summer of 2016 my friend Keith and I went for an expedition right in the heart of the White Cloud Peaks. We left the car on the highest road in Idaho, a dead-end fork at the top that heads south atop a ridge as high as 10,432 ft.

There were no trails, no sign on how to get to these beautiful, amazing White Cloud Peaks, but with one of the greatest Sun Valley Mountain Guides, Keith Anspach, I was in good hands.

We hiked and climbed like mountain goats to get to the camp; after two hours hiking and carrying our heavy backpacks, around evening we found a great spot we could call home for three days. We were surrounded by three amazing alpine lakes, Tin Cup Lake, Dike Lake, and Gunsight Lake.

Our first night at camp, as soon as Keith and I got at camp 9,335 feet, Keith asked me, “hey Flav do you snore?” “Yes, have you ever heard a chainsaw that scratched a chalk board? That’s me.”

Then Keith decided to set his tent up 25 feet from mine so he wouldn't have to hear my snoring. After we were done setting up our tents, Keith cooked us some elk steaks. It was one of the best elk steaks that I have ever had! Soon after dinner we went straight to sleep so we could get up at 4am and start hiking one of the White Cloud Peaks, just to get the best shot of sunrise!

Around Midnight I woke up and went out from my tent; I was amazed at the spectacular view of the Milky Way. I photographed the sky, which was very dark and covered with beautiful stars.

Next day we woke up and we left our camp at 4:00 am to begin climbing one of the White Cloud Peaks at 11,255 ft. It was not easy, but it was worth it. We reached the peak around 5:45am! Keith told me that I would witness the most amazing view and sunrise I ever photographed so far. Here is how it looks: an amazing view and a sunrise from 11,255ft above sea level.

The one on the right side is Tin Cup Lake where our base camp was; on the left side, close to the Chinese Wall, is Dike Lake; further on the left side is Gunsight Lake, close to Gunsight Peak.

The White Clouds Wilderness… what an amazing place on earth!

After a short hike along a stream, past the crowds and along the well-used trail, the landscape abruptly opened into one of the most incredible scenes I had experienced: The Boulder-White Clouds. As a more remote area of Idaho, it supplied us with the less visited mountains, lakes, and streams we had been searching for. Although somewhat controversial throughout its establishment, I immediately felt an intense sense of gratitude overtake me - I was privileged to experience a fraction of what was protected for future generations.

The creation of the Boulder-White cloud wilderness has little impact on how I have experienced the area in the last 25 years, however, it will have a profound impact on how my children and my children’s children will interact with nature.

Preserving portions of Idaho’s great landscape is a lasting investment in the way future generations can appreciate our earth and what true nature has to offer our peace of mind as humans.

We are one of few countries in the world with the resources and interest to preserve land and find ways to use the land without degrading it.

From the first time I unintentionally cliff climbed down into Tin-cup lake from Livingston mill in the early 1990’s to week long backpacking trips into the big boulder lakes and boulder lakes, to a recent visit to Swimm lake, the area holds not only memories, but a desire to continue to return to experience what this small, mostly untouched, area of our world has to offer.

The natural wild areas we preserve, teaches future generations the visible importance of conservation - but only if we take them there to experience it.

On Sunday August 9, 2015 a group of ten of us entered the White Clouds Wilderness Area just above Chamberlin Basin with Castle Peak in the background. It had been a Wilderness Area for only two days. On Friday August 7th, President Obama signed into law the bill creating the three new wilderness areas in central Idaho. This was my second extended trip into the heart of the White Clouds. However, this trip took on a very distinctive and emotional importance for me knowing how this special place is now forever protected for generations to come.

I spent the next seven days photographing a great group of Idaho Conservation League volunteers as we covered nearly 65 miles on foot in the area removing downed trees from the trails with a crosscut saw, fixing water bars, improving the tread, cleaning fire rings and enjoying a true wilderness experience. These efforts to keep public trails open and in excellent shape are organized by the Idaho Trails Association. The trip was capped one evening at the base of Castle Peak when we were joined for dinner and a bottle of celebratory champagne by one of the real heroes who worked tirelessly for nearly 30 years to make the Boulders and White Clouds Wilderness Bill happen, ICL’s Executive Director, Rick Johnson. Rick flew back from Washington D.C. after witnessing the signing ceremony in the Oval Office with President Obama and then hiked all the way in just to be with us just four days later! I still get a tear in my eye when I think about how great it is that everything has come full circle.

You have to work for it! That pretty much sums up the White Clouds, Boulders wilderness areas. Be ready for elevation gains, but the rewards are outstanding.

My first back country experience was backpacking into the White Clouds in 1981. In three days we saw three other people. The White Clouds get more use now, but few other places provide the solitude along with breathtaking scenery that can be found there. Oh, and the fishing is great, too!

If you really want to leave people behind, the Hemingway/Boulders are for you. I was fortunate enough to spend four days there this summer and we saw only three other people, at the saddle between West Pass Creek and the North Fork of the Big Wood River.

The Boulders really represent “wilderness”. It isn’t easy finding your way around, but there are surprises to be found everywhere. Did you know that lupine is fragrant? I didn’t, and it’s my favorite wildflower. A massive field of lupine helped us on our climb to the summit of Ryan Peak (11,714’). When we started working our way up the scree through the lupine, I sensed a wonderful perfume. It took me a few minutes to realize it couldn’t be anything other than the lupine. Because the flowers were so dense and our faces were right in the lupine because of the steepness of the slope we were climbing, the fragrance filled our noses. A sublimely subtle smell!

Did I mention Ryan Peak? Well, the hike to the summit was serious work, but the reward was one of the most remarkable views to be found anywhere. From that narrow, rocky perch we could see nearly every mountain range in south central Idaho. Wow!

Yes, you have to work for it. But, whether it’s the White Clouds, Big Horn Crags or the Sawtooth Mountains, time spent in the wilderness is always rejuvenating and provides memories that enrich my life and enhance my wellbeing. Get out there and collect some memories of your own!

The Boulder-White Cloud wilderness holds a special place in my achievement archives. Six years ago due to physical and mental obstacles, the thought of a hike into any area was never an option. As the saying "Those at the top of the mountain didn't fall there" goes, I climbed and climbed with my son, husband and dog up Fourth of July Creek trailhead…destination Born Lakes to camp. I got to experience the best cut-throat fishing in my life, saw pikas for the first time, spent hours enjoying my family who never expected to see me alive again after my obstacle and being able to live this outdoor experience I had always loved but had been unable to do for a time. It was a perfect hike on well-maintained trails that were well marked and other hikers were courteous and kind, because, they too, had their own stories of accomplishment! I will continue to climb farther and higher time and time again in this "one-of-a-kind" wilderness area and be able to share it with my grandchildren soon.

Maybe it’s just the way it’s played out in my own life, but the difference for me between the Sawtooths and the Boulder-White Clouds is the difference between my teenage years and adulthood. I was all through the Sawtooth wildness as a kid in the 1960’s. The trails were fairly well developed and even the geology -- a product of snow and ice creating those jagged saw teeth – made some sense. I cut my own teeth on the Sawtooths.

The White Clouds… well, they were much less obvious; they required a certain maturing on my part to begin to care about them. And that geology… my God, what is that all about?!

It’s one of the reasons I so appreciate the men and women who fought to keep Castle Peak inviolate back in the 1960’s. You can’t even see Castle Peak from any major road in the state. How did they even know to protect it from an open pit molybdenum mine at its base? How did they get others to care about something you can’t even see without great difficulty? But I do know just enough Idaho history to appreciate that the battle to “save” Castle Peak resulted in some really nice things ultimately happening to this state I call home.

Over the years I have been fortunate to journey to the White Clouds and the Boulders with a group of friends and colleagues carrying HD video cameras and fancy DSLR cameras, to document what makes this landscape so special. Through their eyes, and through a handful of personal trips, I have come to appreciate even more what central Idaho has to offer.

But I’m still trying to get my head around that geology!

Climbing down from my viewpoint on Castle Divide, I felt a new appreciation for Castle Peak and the White Cloud mountains' importance to Idaho. Magnificent terrain, beautiful lakes, and superb mountain beauty. This place has it all for those willing to challenge themselves against its rugged land.

But, there was one more thing I needed to track down. Moving off the trail, my friend and I hiked across the alpine landscape, to a wildflower-covered meadow at the base of the fabled Castle Peak. Today, this spot stands as a reminder, a testament to what might have been.

A half century ago, this was ground-zero for Idaho’s greatest environmental battle: whether to allow the Arizona-based mining company, ASARCO, to build an open-pit mine on a valid claim at the base of Castle Peak. This epic showdown tested the soul of a state that had been settled by miners one hundred years earlier.

The mine didn’t happen, in part because of the hard work of impassioned volunteers like Ernie Day and Jan Boles, backed by skilled political leaders like Senator Frank Church and Representative Orval Hansen. The controversy also spurred the creation of the Sawtooth National Recreation Area (SNRA), helped galvanize public support for protecting more of our state’s special places, and propelled Cecil Andrus into the governor’s office.

As we walked around the meadow, we found remnants of those turbulent times. Over-grown sections of a mining camp service road bulldozed-up twelve miles from the East Fork of the Salmon River valley floor. A discarded 50 gallon oil drum. A capped drilling hole. Down the hill, an exploratory mine shaft and a nearby stream tinged with what looked like mining waste.

I wondered why these things had not been cleaned-up. Whatever the answer, Castle Peak, this meadow, and its abandoned mining scheme stand as reminders three generations later of what could have happened, and what we would have lost.

Interviews

Congressman Mike Simpson is serving his ninth term in the House of Representatives for Idaho’s Second Congressional District. Simpson began pushing wilderness for the Boulder-White Clouds in about 2000 and was finally successful in 2015. This interview was conducted by Bruce Reichert at Redfish Lake in May of 2016.

I bet it’s nice to have it done.

It's nice to have it done. You know, if anybody would have told me when we started that it was going to take 15 years, I would have thought, nah, you're crazy. Because to me, when I started it was a challenge, and then it became a passion, and it seemed so obvious of something that needed to get done. And it had been worked on by many people for many, many years before I came along. But I was ‑‑ you know, collaborative efforts like this, where you're trying to bring in a lot of people from widely divergent points of view, it takes a long time to bring people around.

Some politicians might have walked away from this hot potato, but you didn’t.

Well, you know, the more time I spent out here, like I said, it became a passion rather than just a challenge to get it done.

And the Boulder‑White Clouds are iconic, particularly for Idaho. And they needed to be preserved, not for us. They're not going to be destroyed by what we do today and tomorrow; that happens over time. We need to protect them for future generations that will be able to enjoy these, as we are today.

I've got a relative who has always been a good supporter of mine, obviously. And he's an outdoor enthusiast, loves to hunt and fish and ride four‑wheelers and snow machines, but he always wondered why we were doing this wilderness stuff, why that needed to get done.

And his kids wanted to go fishing one time, so he decided to take them up into the Boulder‑White Clouds. And they went hiking up in there, and he said he got up in there, and he stopped, and he looked around and listened to the quiet and said, "I understand now."

And a unanimous decision. Pretty impressive.

We put it on suspension. And in the House when it passes on suspension, it's usually by voice vote. And nobody voted against it. Anybody could have come down and asked for a roll call on it, and nobody did, so essentially it passed by unanimous consent in the House.

When we sent it over to the Senate, a bill had been introduced before in the Senate, so they had held hearings in previous years. And we decided to try a procedure, which is you hold the bill at the desk, you never refer it to committee, and then you bring it up by unanimous consent in the Senate, and pass it. But that has to have the consent of every senator, because any senator can raise an objection, and it won't happen.

And, in fact, when my chief of staff, Lindsay Slater, came up with the idea -- it's a very rarely used procedure -- and the staff on the Senate side of the committee said, "Oh, don't do that; it will hurt you. You'll never get it done if you do that," and all that kind of stuff. And we said, "What have we got to lose, let's go for it."

So Senator Risch helped us, and he made sure that on the Republican side none of the objections came from the Republican side. And Martin Heinrich, a senator from New Mexico, who's a Democrat, and he helped us on the Democratic side. And surprise, surprise it worked.

So there's always winners and losers in any decision like this.

Well, in any compromise, in any collaborative effort people have to give up a little bit of what they want in order for the greater good to accomplish the goal.

And if you talk to the recreationists, the snow‑machiners, the mountain bikers, the people that like the outdoor recreation stuff on motorized vehicles, they gave up some. But we maintained most of their access to their areas that are really important to them. The environmentalists gave up some areas that they would have liked seen put in wilderness, so it's a smaller area than some would have liked to have seen.

That's the nature of a compromise. But when you can walk away from it and say, overall, this is a good deal. And I think everybody can say that.

I imagine the threat of a Monument played a role in this.

I can't say that it didn't. The ICL decided to start pushing that, because, I mean, we've been working on this for 15 years. I've been coming here to the Wild Idaho conference for 15 years, saying, next year, we'll get this done next year. And patience wears thin. And I think they thought that, you know, maybe the way to do this is to do it as a national monument; we won't get a wilderness area, which is the highest protection that we could designate this land.

And so they started to pursue that. And I think the threat of that pushed some people into saying, yeah, we need to sit down and see if we can come to a resolution on this, on a wilderness bill. Because with a national monument, you don't know what the management plan is going to be, what the boundaries are going to be. That's all written in Washington, DC. With this wilderness bill, it's written here by Idahoans, with Idahoans' input.

I think a lot of people are looking at this, saying, it didn't seem to hurt Mike Simpson. Maybe there's a place for this kind of collaboration.

Well, hopefully it does. I mean, that's what's needed a lot more. I mean, politics, you know, when you think about how diverse this state is. And whether you are someone who is opposed to any more wilderness or someone who wanted the whole darned state in wilderness, we all love this land and want to enjoy it, and we want our future generations to enjoy it. So that means coming together and talking together with people from different points of view.

And I will tell you, even if had we never completed this, had this bill not been signed into law, this effort would have been successful because we have people talking with each other that would have never talked before, would never sit down at the same table. Now they actually talk to each other. That doesn't mean that they always agree, but 90 percent of it is talking. And that's what people are starting to do.

I think this will lead more politicians to say, yeah, you can go out on a limb and try some things and see if you can bring people together to solve some of the environmental problems we have. And in this state environmental problems are huge because we have so much public lands.

And everybody believes that they can manage them better than the land managers that currently manage them. And so that's a challenge for Idaho. But I tell you what, it's like Ernest Hemingway said, "A lot of land this Idaho."

So was it worth 15 years?

Absolutely. Absolutely. Like I said, if somebody would have told me from the beginning it would take 15 years, I would have gone, "I don't know that I'll be here 15 years."

People talk about term limits and how those that have been here for a while are the problem. The reality is if someone wasn't in Congress trying to do this for the last 15 years, it still wouldn't be done. If every four or six years you turn to a new congressman, eventually a congressman is going to go, Why do I want to do that? Why do I want to take on that challenge?

It takes some time to do big things.

Rick Johnson is the director of the Idaho Conservation League. This interview was conducted by Bruce Reichert at Redfish Lake in May of 2016.

It’s been a long, windy road to get to Wilderness for the Boulder-White Clouds. Do you have any thoughts about when it all started?

The White Clouds story goes back to Cecil Andrus and the mine. But the modern chapter is really about Mike Simpson and moving the bill forward.

And in a lot of ways that started right here at Red Fish Lake, where Idaho Conservation League has an annual conference, we call Wild Idaho! And we invited Mike for the first time during his House career in 1999. And we started talking to him about the White Clouds then. We took him on an overflight of the peaks, and we stood in the airstrip and talked about how you get these things done. And that began the conversation.

Some might say Mike Simpson is not somebody that you would necessarily think would be receptive to wilderness.

In the beginning he said, "You know, Rick, you've got to understand that my idea of wilderness experience is when my golf ball gets caught in the rough. So it didn't come naturally, but politics comes naturally. And he saw a challenge. And Mike Simpson is a doer. He saw something that other people hadn't been able to do. And he said, "Well, by golly, I can do that." And, you know, I don't think he ever thought he was getting on a 15-16-year-long train; but, nevertheless, I think he saw it as a political challenge.

But what happened later is he started going out there. And he went out almost every year for a while, brought his staff, frequently. He never brought reporters. He wasn't doing it for show. He was going out there with his watercolors. He was going out there just to spend some time, and it changed him. He fell in love with the place like everybody else has.

And it became personal. And, you know, it's certainly always been personal for me. But, you know, that's my job; I mean, it's my love. I love the White Clouds. But for Mike... to watch that evolution happen and for the relationship to develop, it's pretty powerful.

And you also had to fall in love with the White Clouds.

The very first summer I lived in Idaho, in 1979, my very first trip was into the Boulders. And from then on into the White Clouds. I did a ski trip for over a week in the early '80s.

Extraordinary stuff. I'll never, ever forget the first time I saw Castle Peak. And, frankly, it changed my life.

The interesting thing about Castle Peak is it's such an important mountain, but you can't see it from anywhere.

I think it's emblematic of a lot of things about Idaho; you have to go a little further to catch it. You have to work a little harder to get to know some of the parts about Idaho. It's not the Tetons, or it's not Yosemite. So many things about Idaho you have to work a little bit.

I think one of the things about the White Clouds, too, is they've always been bigger than just the mountains. They've always been bigger than just the East Fork of the Salmon. They've always been bigger. And it started because it was part of the Sawtooth conversation. But, again, you know, off the main road, a little harder to see.

And then the whole history of the moly mine and ASARCO and the governor's race. I mean, who would have imagined that protecting Castle Peak, arguably, helped make 100 million acres of Alaska protected, because a guy got elected governor, Cecil Andrus, who then, because of the White Clouds, became Secretary of Interior. And then later, you know, the whole story begins again.

So Mike Simpson is the Republican version of Cecil Andrus?

Mike Simpson is, arguably, becoming one of the new voices of conservation in the way that Cecil Andrus was one of the old voices. And Mike Simpson has come so far in figuring out how to make Idaho solutions in DC.

Castle Peak really became emblematic of the whole modern conservation movement here. It captured the imagination of all citizens because, frankly, they had to vote on it. It became the centerpiece of the 1970's governor's race. And that led to countless efforts beyond that, everything from the Middle Fork to Hell's Canyon to the Selway, all these things that stitched together the legacy of Frank Church, the legacy of Bethine Church here in the Sawtooth Valley.

But in the end, the White Clouds became this sort of larger-than-life story, because when this conservative Republican from Idaho introduced a bill, they're like - in Washington, DC - what is this about? And then that he kept flogging it for another 15 years. I mean, he became famous for this in Washington, DC. A lot of Idaho people forgot that it was even going on. But he had established a profile with his colleagues and with other people.

And he had the picture on his wall in his office. You walk into Simpson's office, and it's like, What is up with this place? Why does it matter so much? And, you know, those are the unanswerable things about what it means to live in Idaho, what the word "Idaho" means, what does - why does it matter so much to all of us? Everybody has some special part of Idaho, and Castle Peak is really emblematic, I think, of all those places.

Congressman Simpson’s reputation doesn’t seem to have suffered by being aligned with a wilderness bill, in a state where not too long ago you could get into a fight for advocating wilderness.

Well, I suppose that's still possible. But one of the things that I think people are craving for right now is they want to see our government work. I mean in Idaho you can't find anybody that is more proud of being an American than somebody from Idaho. But our system of government is not working at its best these days. And I think that's part of it. Also, getting a bill passed for a place that Idahoans love, it reminds you that democracy works, and people can actually come together with different interests and get the job done.

So were you surprised that it was a unanimous vote?

This took a long time. But, I think of it as sort of the Sisyphus myth. where you're pushing the giant rock, you know, the giant rock up the mountain, and it kept rolling back down on us, it kept rolling down on Mike Simpson.

And he said, "Rick, you know, if it was going to be easy, it would have been done by now." And he never gave up, we never gave up, and together we reached this point where all of a sudden, you know, this rock's rolling downhill. Part of that was the national monument, but part of it was we crossed a certain tipping point, or whatever phrase you want to use, but that rock started going downhill.

And it had to pass unanimously. If it had a recorded vote, then it's going to be different. It had to happen the way it did. The fact that it did is a miracle, but it had to happen that way.

But for a while, you supported a National Monument instead of Wilderness. That must have been hard to swallow for a lot of your supporters.

We've been working for wilderness in the White Clouds for a long time. I personally have been doing it for over 30 years. Wilderness is the gold standard of protection in America today. It is also a standard of protection that Idaho understands. We live with wilderness, and so - it's always been the goal.

Now, after you fight a campaign for 15 years, and you're failing to get there, and all you can see in Congress is more polarization, more division, the chances of really getting it done were getting, frankly, more bleak.

The decision as to whether it's a monument or whether it's wilderness, I think there's a lot of trust from the conservation community in organizations like the Idaho Conservation League. We'd worked on this for a long time, we cared deeply about it. It's about protecting the values of the place. It's not about politics. It's not about personalities. It's about what can we do to permanently protect the values of the White Cloud ecosystem.

And, frankly, wilderness in Congress wasn't looking like it would work. And so we had to shift the strategy.

President Obama has now designated 22 national monuments. This was a very viable strategy. It came to us through Cecil Andrus. He came to our Wild Idaho! Conference right here and challenged us to put Congress aside and start focusing on a national monument. And we embraced that challenge, hard as it was, to create a national campaign. Because that's different than getting your home state delegation. This is actually going above the home state delegation and trying to get the president of the United States to do something in a state that would never vote for him.

So the monument, we reached a point where one of two things were going to happen. It was either going to become a national monument - and we had conversations at the highest level of this administration - or it was going to be a catalyst for the delegation to get back to work. Both those things happened.

It became clear that a monument was going to happen, at many levels; you could just feel it. And then Jim Risch, Mike Simpson, sat down, made some hard choices, other interest groups came to the table, and in a matter of just a couple of weeks they got that done.

Let’s talk about each of the three wilderness areas. How would you describe them?

Well, and to be honest, the Boulder-White Clouds, you know, in the earlier history it was always "the White Clouds," and we attached "Boulder" because more people knew where the Boulder Mountains were. And, frankly, it was a marketing thing, Boulder, hyphen, White Clouds. We wanted the identity to be for those two mountain ranges and for people to understand the interconnectedness of that ecosystem.

I wish the borders were a little bigger, but to make the compromises, we had to - that's just how it had to go. But the Boulder-Hemingway chunk of country really focuses on the front range of the Boulder Mountains, the incredible wild country that's immediately in back of it. Then you have the classic White Cloud peaks with Castle Peak and the stunning lakes. And, you know, that will be probably the part that is most visited and most well-known.

But the real gem is on the other side of the East Fork of the Salmon, and that's the watershed of Herd Creek in the Jerry Peak Wilderness. And that is watershed-based; it's the biggest piece; it is some of the best wildlife habitat, the best opportunities for scenery, the best solitude that you're going to find. The real gem is over there. But it is an extraordinary diversity of mountain, river, sagebrush habitats, all found, it's all in those three places.

Any last words?

It is the only wilderness bill that passed the US Congress in 2015. And I think it's important for people to realize in this presidential administration they've signed four wilderness bills, half of those have included Idaho. That's about people working together, creating the art of the possible, bridging divides between left and right and actually putting Idaho's interests first.

And I think Mike Simpson, Mike Crapo before that, Cecil Andrus, Frank Church - there's a legacy - Jim McClure - there's a legacy of people that put their shoulder to the wheel. And Jim Risch deserves a lot of credit for getting it through the Senate. But Mike Simpson had the vision, and, frankly, he never gave up. And he'll be remembered for that.

Senator Jim Risch was elected to the U.S. Senate in 2008 and is currently serving his second term as Idaho’s 28th Senator. He sits on five committees, including the Energy and Natural Resources Committee. Risch also served as Idaho’s 31st governor. This interview was conducted by Aaron Kunz in 2016.

Senator, why was it important for you to be involved in this issue?

Well, first of all, I certainly don’t want to exaggerate my part in this. This was Mike Simpson’s bill. He’s been dedicated to this and working hard on it for decades. And he’s the person who really should get all of the credit. Unfortunately, after he drew the bill in the first place many years ago, it got back to Washington, D.C. and back there things were a little out of kilter and it got tilted badly away from what Idahoans really wanted in the bill. So it bogged down, and that lasted for quite some time.

But Mike didn’t give up; he kept after it and kept after it and finally went back and resurrected it, starting essentially over again with the skeletal outlines of the bill that he had, brought the people to the table and we got a bill that was an Idaho bill again; and he was able to get it through the House, and I was able to move it through the Senate.

So, it was done on what we call a collaborative fashion. That’s the only way these things get done is if you get all of the stakeholders around the table. When I was Governor we were dealing with 9.2 million acres of roadless lands and I used that model, the collaborative model, to bring everybody together; and we actually got a rule that now applies to all of what were roadless rules in Idaho; and we’re the only State essentially in the country that has that, and it was done because of the collaborative method.

When you’re talking about collaboration, you had to convince Senators who would be very against this type of bill. How did you convince them?

The way I did this was very simple; I said, “Look, this is Idaho’s bill. This isn’t a bill that was put together nationally. It was put together by Idahoans for Idahoans.” And it was done in such a fashion that we had motorized users, we had all of the people that were stakeholders, the preservationists, everybody was at the table, and it was done in a give and take fashion. And if you do sit down and do it in a give and take fashion, and you do that where people have some level of trust, it can be done. And that’s how I was able to convince other Senators that this was the way to do that.

I think a lot of people were shocked at how quickly it came about, but I imagine there were a lot of moving parts that the public did not see.

And you’re right on that; it appeared quickly, but this had been in the works for decades. So it didn’t come together instantaneously by any stretch. I’ve been working on the Scotchman’s Peak area for some time, for a number of years. We hope to have an important announcement on that a little later in the year, but again it will seem, “Well gees, this just happened.” Well, no it didn’t just happen; it’s been in the works for a long time.

You’ve been Governor here in the State of Idaho. You’ve been a public servant of Idaho; why was it important for you to support a bill like this?

Well we’ve got some really magnificent lands in Idaho. And it’s really important that the choicest of those lands be protected for future generations. And to do that, you do need to have the collaborative system so that everybody has a voice in this and it’s not bigger than what it needs to be, but it is sufficiently large enough that it does protect the more spectacular parts of the land that we all love and recreate on here in Idaho.

First of all, Mike Simpson deserves all the credit on this. But the way this happened was he used the collaborative system where you bring all the stakeholders to the table. I had done the same thing when I was Governor when we were trying to do an Idaho Management Plan for the nine million plus acres of roadless lands that we had here in Idaho. And the only way that can be done is to bring all the stakeholders to the table. Not only the recreational users, the motorized users, the people who are total preservationists who want to stop everything; they need to come together, it needs to be a give and take. Everybody’s got to give a little and everybody gets a little, and if you get some trust going in that fashion, these things can be done. Mike did it there, I did it on roadless. Mike Crapo did it in the Owyhee properties; so this can be done. The only way it gets done is with a collaborative approach.

But compromise and collaboration seem almost not the Washington, D.C. way to a lot of people.

Well, it’s the only way to get things done. And there’s a lot of it that goes on back there, but it’s not newsworthy. The media doesn’t cover everybody getting along and getting the job done. If there’s a fight, that’s got some appeal for people who are watching the news, so they really concentrate on that. But look, if you didn’t have some give and take, the government wouldn’t operate, it couldn’t operate. So there’s a lot of give and take that does go on to get to that point, but it certainly doesn’t make the headlines like a fight does.

Cecil Andrus served 14 years as Idaho’s governor, longer than anyone else. He was also Interior Secretary during the Carter administration, from 1977 to 1981. This interview was conducted by Bruce Reichert in 2016.

Three new wilderness areas. What’s your reaction? Are you happy?

Well, that's always a question that people will ask. But the winners are the public. I don't care whether it's all or part of a pristine area to be protected. When we protect it legislatively, it's a win for the public.

Let's take the Boulder‑White Clouds, for example. There was the group of Sandra Mitchell, who had more influence than she should have on Senator Risch, and all of the motorized recreational people. They got an extra bite out of that. I preferred Mike Simpson's original bill. And I was an early-on supporter of that. And then when Risch went south on us and tied it up, we had to come up with a vehicle. We used a monument of utilization in the Alaska Lands Bill to bring the people back to the table. So some of us decided that maybe we could do the same thing here.

There were hundreds of people that worked on that wilderness. But the two that really deserve all the credit is the congressman, Mike Simpson; he worked for years, and he never quit. And then, of course, Rick Johnson of the Idaho Conservation League. Rick lived on airplanes back and forth to Washington. Those two were the mainstay.

My role was a long-time supporter of wilderness -- but my role was to keep the monument activity alive and active. And I would say to you if it hadn't been for the threat of a monument, they never would have agreed to come back to the table. But once the White House let it be known, privately behind the scenes, if you don't have a wilderness bill, then the president will take executive action. That moved them back to the table.

But they would prefer a wilderness designation legislatively than a monument, and so would I. That would be my preference because that is accomplished by legislative action. And with a monument there are management plans that can be manipulated by any number of individuals: bureaucrats, or special interest folks. But the threat of the monument brought them back to the table.

So we didn't get all the acreage that we thought we wanted, but we got the protection on the main core of everything, and it was a win situation. So am I satisfied? Yes.

You and President Carter used the Antiquities Act of 1906 and Monument status when you were Interior Secretary in Alaska. Could you recount what you did, for those who weren’t born yet?

A lot of people don't understand what we had to do in Alaska. But Alaska is that part of the world where we had the opportunity to do it right the first time. And President Carter was a very, very strong supporter of the necessity for finalizing that during his presidency. And as his Secretary of the Department of Interior, he kind of took me off the leash, so to speak, and said, "All right, you lead on this." But, again, it wasn't me; it was a whole bunch of people that were working.

But we had the nonbelievers in Alaska that knew that there was a time frame when the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act would expire, and they could go in and gobble up all of the special places. Well, we extended that a year. They still refused to come to the table. And I had staff do the research on the Monument. And I arranged a meeting with the president in the White House. And Stuart Eizenstat, who was his domestic advisor, brilliant man, was there with us. And I said, "If we do this, we will protect that land so that they can't step in. But also I think it will cause them to come back to the negotiating table, and we'll finish it."

And I remember the president looked at Stuart and said, "Can we do that?" And Stuart said, "Yes, Mr. President, we can." And he said, "Consider it done."

And he withdrew hundreds of thousands of acres under the Antiquities Act as a Monument. And under the secretarial provision of FLPMA, I had the opportunity to withdraw another sizable amount. And I remember Alaska Senator Ted Stevens called me up immediately on the phone and jerked me up to the hill; you know, they loved to pull bureaucrats around; and I dutifully had to go up and sit down.

And he said, "Mr. Secretary, you have misused the Antiquities Act." And I said, "Senator, maybe you think so, but it's absolutely legal, and it's done, and all I'm asking is that you, in good faith, bring the people back to the table and that we get this resolved." And he's a man of his word. He said, "Okay, we'll do it."

And he and I met a lot of times, privately. And in the political world you do some little different things. And he would go to Anchorage and to the Anchorage Times newspaper and just -- he'd tell me he was going up -- and he just was going to take my hide off. And he would say that blankety‑blank so‑and‑so Secretary Andrus, you know, and then he'd come back, and we'd sit down and work out some deals. He had a tremendous amount of knowledge of Alaska. And he could tell me where some of the mineralized areas were. And he was very helpful in that regard.

Now, he wanted a little more than we gave him, but it worked out. And in 1980, between the elections, the president signed the bill. And again, a tremendous win for the world.

So, anyway, the Alaska Lands Bill more than doubled all of the national park acreage in America. We protected 103,000,000 acres with the stroke of the president's pen. And it was a victory. But the utilization of the Antiquities Act was the key to bringing some of those hard‑nosed right‑wingers back to the table.

Your comments about you and Alaska Senator Stevens reminds me how you as governor, and Mike Simpson as Idaho Speaker of the House, managed to get along.

When the Congressman was the Speaker in the Idaho legislature, yeah, we had differences of opinion, but he'd come down to the office -- I couldn't go to the third floor -- but he'd come down to the office, and we'd sit down and resolve the problems. And we always were able to communicate with one another.

And when he started the work on the Boulder‑White Clouds area, I was one of the early supporters. And, again, Rick Johnson kind of engineered that get‑together. And I have tremendous respect for Mike. He's worked hard.

But, anyway, politically, that's the good days. But he, Phil Batt, myself, people on both sides of the aisle, we weren't rancorous and spiteful and hateful. We had differences of opinion, but we'd sit down and work out a deal. And I don't know who said it, but politics is the art of compromise. And that's what's taken place in every wilderness debate.

Several folks have wondered, so what does Castle Peak in the White Clouds have to do with the Sawtooth Mountains?

Oh, a lot. In 1970 the issue of Castle Peak and the molybdenum mine, ASARCO's legitimate mining claim in that area, was the first time that the public saw a long period of time of debate; and the educational aspect of the importance of the environment is something that they got a taste of. And they knew that it was a situation where we could explain the destruction for just simple economic gains. It was a mineral that was low‑priced and, at that time, it wasn't needed.

So then that election took place. A funny thing happened in 1970: a Democratic lumberjack from North Idaho stumbled into the governor's office. But two years later Senator Church, myself, and others, worked to create Sawtooth National Recreation Area. And that was the controversy of Castle Peak, and the moly mine there and everything was still fresh in the minds of the people.

And Ernie Day and his photography of Railroad Ridge, Bruce Bowler, Ted Trueblood, all those people were there to remind the folks that, hey, this is a very unique, pristine area. It didn't qualify for wilderness because of the inholdings throughout it. But it did qualify for a national recreational area, which we have today. And the beauty and the majesty of the Sawtooths is there for us to enjoy, and for future generations to enjoy.

So I think young people today might say, sure, every politician is going to get behind this notion of stopping ASARCO at the base of Castle Peak. But those were different times. I mean, there were some political liabilities to taking that position.

The governor of the state of Idaho, at that point in time, and his director of the Department of Commerce were very vocal. Industry was not exactly enamored with that lumberjack that became governor and some of the proposals. But, again, we worked our way through it, and now that area is protected.

Keep in mind, though, it really wasn't protected until the Boulder‑White Clouds passed in wilderness status. It's a situation where they had a legitimate mining claim, and we blocked off access and created a protection for the East Fork of the Salmon and some other things. But that was the beginning of a lot of wins.

And, today, people don't understand it, but Idaho is second only to California in the Lower 48 in total acreage of wilderness. And there's still more we have to look at: the Pioneers, the Upper St. Joe, the Upper Clearwater, some others. There will be plenty for you young people to do out there when guys like me are long gone.

For you, Castle Peak really was one of the touchstone subjects that really kicked off your statewide political career.

I have a beautiful photo of Castle Peak, framed, in my home, and the caption that I have for it when people point to it, I say, "Yes, that's the mountain that created a governor." I mean, it is. You know, it gave me that edge in 1970.

And then there was a lot of publicity nationwide, that this is the first gubernatorial election where an environmentalist was elected as governor of a state. And so, yeah, that was a situation where the people got involved.

And it really led to a whole series of conservation victories that wouldn't have happened.

You just click them off. And people have forgotten that what we now call "The Frank," but the River of No Return Wilderness Area, that wasn't finalized until I was Secretary of the Interior, and we got it passed. And, again, it was signed during the lame‑duck session of 1980. And then after we lost Frank, and then it was named the Frank Church‑River of No Return Wilderness Area. But Bruce Bowler, Ernie Day, and Ted Trueblood, some of those old-timers, they had a lot to say about the importance of those unique, pristine areas.

Now, I mentioned almost 6 million acres of wilderness. But there's 54, almost 55 million acres of land in Idaho. So that's, roughly or approximately, 9 percent of the area. So there's plenty of other areas for the utilization of commerce, of motorized vehicular activities. There's room for all of us if we just use our heads and sit down and work these things out.

Now, again, Scotchman Peak, good example, everybody is for it. It's hard to find anybody that will argue the other side. But maybe we're through puberty and into adulthood.

Any thoughts on mountain bikers wanting a part of Wilderness?

What do we call it, a new generation of users of the topography of Idaho. Some people want to present a dry fly to a rising fish. Some people want to ride their bikes, like the gentleman that rode through here a moment ago. Those people who hunt upland game birds. All of the various -- elk season, deer season -- all of those activities are out there with people that like to enjoy. That's part of Idaho. That's why we live here. That's why it's so important that we don't ignore anyone.

But I would submit to you that 9 to 10 percent of the land being held in wilderness status is not a very large amount. It sounds like a large block of land, but it's those pristine, unique areas where we were trying to salvage a remnant of some special something, unlike Alaska, like I said, where we had the opportunity to do it right the first time.

So we've got a piecemeal, a mosaic, if you will. Or if any of the ladies that might be watching make quilts, you know how they save little pieces of cloth to put into the patterns of their quilts? That's really what we're doing with the real estate.

Ed Cannady has been traveling the backcountry of the Boulder/White Clouds for over 40 years and has worked for the Sawtooth National Recreation Area for more than 25 years as a wilderness ranger and backcountry manager. This interview was conducted by Bruce Reichert in 2016.

You know the Boulder-White Clouds as well as anyone alive. What’s your take on the Wilderness designation? Who were the winners?

The thing that benefits the most from the passage of the wilderness bill is the place itself. The place will be as it is today in perpetuity now; that's guaranteed. The place commands respect from people as soon as they experience it. For a lot of people that's just through photographs. But once you visit the place, it just sets its hooks in you, and it will not turn loose. And so that loyalty that people are going to have to that place for the rest of their lives, will benefit it for the rest of time, certainly for several lifetimes.

So the place, itself, was the primary winner. The wildlife and the plant species and the fish species that inhabit the Boulder-White Clouds, they're the winners. They're the primary winners. And the people who like to go visit amazingly, astoundingly beautiful places.

The pace of our lives have increased so dramatically over the past 120, 150 years, light-years, compared to how slowly the pace of life changed over the previous several thousand years. We've just made this amazing leap forward, and our lives are so much busier and so much more frenzied and harried now. So to be able to go to a place that is going to be peaceful and quiet, where you slow your pace, people who enjoy that and who realize the benefits of that -- and science is increasingly documenting how important that is to people for mental and physical health -- the people who want those benefits are the secondary winners from the wilderness bill.

There are three wilderness areas. And each one is different. Give us a brief explanation of each.

The White Clouds have the most trails. It's the most heavily used of the three wilderness areas; it has the most trails, it has the most lakes, between 120 and 150 alpine lakes, depending on how you define a lake, a lot of them with trails to them. And in the White Clouds the terrain's pretty kind, even given how vertical it is, so it's pretty easy to go off-trail. So the White Clouds get the most use. It's also, probably, the most scenic, even though that's a tough call because they're all three exquisitely beautiful. So the White Clouds have more use. You can always camp by a lake, if you like. And it's easier to access.

The Boulders are tough to travel, very few trails in the Boulders, and most of the trails we do have just go up into a basin and end, dead-ends at a headwall. I'd call traveling in the Boulders graduate-level travel. Challenging, steep, loose, they're all just big, huge rubble piles, but astounding terrain, wildlife rich. You earn your rewards in the Boulders, but the rewards are great.

Solitude is easy to find in the Boulders because most people want to camp by lakes, and they want trails, so a lot tougher to access, but if solitude and silence is truly what you're looking for -- I don't like to be selfish, but people can do their homework and figure it out for themselves. And most people if that's what they're looking for, they're willing to do that to find it.

The Jerry Peak Wilderness is very remote, not very many well-maintained trails. And that's not a knock on the trail maintenance; it just doesn't get the level of use that makes the efforts to maintain the trails worthwhile. But extremely important wildlife winter range. Lower elevation, but steep and remote. You have to be good at orienting yourself with maps to do much travel there, but solitude, again, is really easy to find.

So you have these three wilderness areas, all of them different from each other. That must put a bit of a burden on the agencies administering them. And as we all know, Congress is not always quick to throw money at something that they've designated. What do you do if you're an agency?

Well, we seem to always manage to find a way to do what needs to be done, not to the level we would like, maybe. But what is going to be required will come out of the wilderness management plan that's being developed. So we won't really know exactly what we have to do until the wilderness management plans are completed. And the public will have a lot of opportunity to be involved in the development of those plans.

Our hope in the White Clouds and the Hemingway-Boulders is to have a draft management plan out in the spring or summer of 2017. And then the BLM and the Salmon-Challis National Forest are doing the wilderness management plan for the Jerry Peak. And their plan is to have it sometime in 2018.

We definitely have experience managing wilderness. But the BLM has experience with wilderness. They have the Owyhee Wilderness areas now. And the BLM is a real dynamic agency. I'm not concerned about their ability to take hold of it and deal with it.

You’re known for your photography. Photographers surely will love these new wilderness areas.

It is an amazing place for photography. And it's not that well known, in comparison to places like Oxbow Bend and Grand Teton or Schwabacher's Landing and places like that. But I like to get different perspectives than you see from Sawtooth photographs. I have a lot of photos of Little Redfish Lake, you bet. Everybody does, how could you not?

But I like to climb the ridges and think about where the sun's going to come up, where it's going to set. What time of the year am I going to shoot if I want a spring shot. Or fall, fall is one of my favorite times to shoot, of course. So I'm willing to burn the calories to get that different viewpoint, to climb a ridge and sleep out. I got driven off a ridge by a storm last fall, where I had to hike out in the dark because I didn't think I was going to make it if I didn't. So I'm willing to take those chances to get the unique shots of both the Boulders and the White Clouds.

And as far as people seeing that photograph and saying, "Oh, yes, I've seen that," that doesn't happen nearly as often. But as far as people seeing the photo and saying, "Wow, that's an amazing place," that happens a lot more often.

Sounds like you’re not afraid of snow and rough conditions!

I suffer well. And that's a prerequisite for doing a lot of the trips that I do. And, yeah, I'm willing to carry a heavy pack. I've said before that I'm fortunate in that the only addiction I've ever dealt with in my life is carrying a heavy pack in steep country.

Well, the storm last fall, I knew it was going to storm, so I took my little one-person tent. And the storm was so severe that my tent was about to leave me. It was about to be shredded. I was afraid a tent pole was going to break and stab me in the face. And I thought, I can't do it without a tent, so the best thing for me to do is get up and pack up and hike out by headlamp. And so I did and just slept the rest of the night -- or spent the rest of my night, I didn't really sleep -- in the back of my truck.

A couple of summers ago I slept on top of a peak in the White Clouds where there was barely room for me to lie down. And I had a sleeping pad on the ground. It went flat at 1:37 a.m. -- I still remember the time -- it went flat. And sleeping on the ground there was not a possibility, so I just sat up the rest of the night with my feet hanging over the edge. The good thing was I didn't have to set my alarm to shoot the sunrise.

I travel by myself a lot, easily 90 percent of the time. And I know by going by myself I'm taking additional risk, so I take additional precautions. It can be a pretty cerebral activity to figure out how to do this safely. I'm not afraid to turn back. I realize that a lot of things I'm going to try are not going to work. And if it gets too sketched out, I'm not at all afraid or too proud to turn around and come back and try something else.

I like to look for metaphors in nature. I've learned that what often seems like a huge obstacle in your life will be an obstacle, but there's almost always a way through. There's almost always a way to get over that obstacle. It helped me tremendously when I'd had cancer. When I dealt with my cancer, I viewed that as another obstacle; I was going to find a way through.

It’s been a year since the creation of the wilderness designation; I’m curious what kinds of comments you’re hearing from people.

Gratitude. I've heard a lot of gratitude, a lot of thanks, and a lot of recognition of how special the place is and how richly it deserved the wilderness designation. As I said earlier, the place commands respect as soon as you experience it.

Mike Simpson has told the story that he appreciated the place and wanted to make an effort to protect it, but when he finally stood on top of Chamberlain Divide and saw that view of Castle Peak, that's when he knew he had to do what it took, whatever was necessary to make it happen. And the place has that effect on people. And so people truly do appreciate -- not everyone, of course, but that's never going to be the case -- but people truly do appreciate that finally this place has the protection it deserves.

It's important to remember that the Boulder-White Clouds have always been special. They've always been an amazing place. On August 7th of 2015 the US Congress and the American people finally acknowledged how special the place is by designating it as wilderness. But the place didn't change. It did not change anything on the ground. The place was still just as special as it was 20 years ago; it just has that official title now.

On one side of the wilderness is Sun Valley/Ketchum; on the other side, Challis. Talk about ying and yang. How do you deal with that?

Well, you deal with it by talking to everyone and listening to everyone. Everyone recognizes how special the place is. Everyone has different issues that they have to deal with. Custer County has the problem of being 96 percent public land, pretty small tax base. So they have real issues that they have to deal with that Blaine County -- it's different for Blaine County. So we talk to them and try to find solutions working with them, and same thing with Blaine County.

But it is pretty interesting how dramatic the difference between the two counties; that dividing line, they abut right in the middle of the SNRA. But we treat both with respect and have good dialogue with them and try to come to solutions that work for everyone.

Were you surprised that it was a unanimous decision by both Senate and House?

Yes and no. Yes, in that it's hard for Congress to agree on anything. But, no, because of how hard Congressman Simpson worked and how much work had gone into it over the last many years. And, again, the fact that the place sells itself. The photos that were shared with people in Washington, DC, the people who actually came and visited the White Clouds, in particular, the place sells itself. So I was surprised because it's Congress, but I wasn't surprised because it's the Boulder-White Clouds.

You had an opportunity to recently spend time with Congressman Simpson near Castle Peak. That must have been interesting.

Oh, it was amazing. You know, we had celebrated a couple of times already. But to actually be in the wilderness with the congressman and the chief of the Forest Service and Rick Johnson and Rocky Barker, and others who were a part of this story for a very long time, to actually be there and drink a toast to Castle Peak, at the foot of Castle Peak, was amazing. It was just one of the best trips I've ever done. The feeling was just euphoria the whole time.

Craig Gehrke is the state director for the Wilderness Society. He is an Idaho native who grew up on a cattle and wheat ranch. This interview was conducted by Bruce Reichert in 2016.

Three new wilderness areas, the newest in the nation. What did the nation gain?

The Boulder-White Clouds is unique even for Idaho, because you have three very diverse landscapes and a very diverse wildlife and fish population. It's almost 900 miles to the Pacific Ocean for those fish that are going up the East Fork and up Herd Creek. You have bighorn sheep, you have pronghorn, you have mountain goat, you have wolverine, you have all the game species. And even for Idaho to have that kind of diversity, in a relatively compact area, is just special.

And that's kind of why the White Clouds have stood out for so long, is that folks have realized, first, they're a spectacular mountain range. I mean, you see them from a ridge, say, in the Jerry Peak Wilderness; looking back across the White Clouds, it's a stunning landscape. You see them from Horton Peak on the Sawtooth side. And it's like, wow, this is one of Idaho's unique places.

So I think what we've gained is the commitment that Idahoans started a long time ago, that this place deserves the best we can do for it.

They’re 20 miles from the Sawtooths, and they look quite different from that mountain range.

You're on this very characteristic granite for Central Idaho. And then you're in the White Clouds, and you look around, and there's bits of agate on the trail. And you have the basalt formations here. So just in that little space is completely different, and it is noticeable.

And then the color of the White Clouds, I mean, that is just spectacular. And you see some of Mark Lisk's work and the photography he's done, it's like, man, I mean, talk about a range of light. And even as beautiful as the Sawtooths is, you don't have those stark-White ridges that cap the White Clouds.

And what about the Jerry Peak area?

Jerry Peak is largely managed by the Bureau of Land Management. And clear back in the '80s they had recommended that to be a wilderness area. And about the same time the Forest Service had recommended the core of the White Clouds to be wilderness. The country in between, nobody looked at that. The agencies certainly didn't consider a landscape look at this.

So one thing that Congressman Simpson did in his bill was he put those two individual wilderness areas together in one and the connection between. And it's incredibly diverse wildlife habitat because it's aspen, it's willow, it's sagebrush, it's grass, it's forest, it's up into the high country around Jerry and Herd Peak itself. Those transitions are important for wildlife because it gives them summer/winter range there in one spot.

The conservationists, back in the early 1980s, had proposed a half million acre Boulder-White Cloud wilderness, which included all that country, and, of course, we had supplied the maps to the different Congressional delegations considering wilderness, and it caught Simpson's eye. And he thought, yeah, this is something we could do that makes some sense on the land, to have the diversity of land types, habitat types, protected in wilderness, and connect these two places that the agencies and folks had supported for wilderness.

I think Jerry Peak surprised a lot of folks. They had heard of the White Clouds and the Boulders, but Jerry Peak, not so much.

It gets back to our biases, to some degree, because a lot of times you don't think of that more sublime country as being wilderness. We think of the White Clouds proper, and you think of the Sawtooths, and you think the Crags, oh, yeah, that's wilderness. But a lot of times the most important wildlife habitat is the relatively more gentle country.

And I can guarantee you that if you're looking for solitude in the White Clouds, you're going to go to Jerry Peak. Because you go up the trail, you go up Bowery Creek, you go up West Pass Creek, you go up Herd Creek, chances are you're not going to see anybody. So if you visit that country and you want to get away from others and have a real wilderness experience, after folks get familiar with it, they're going to head to the Jerry Peak Wilderness.

How long had wilderness advocates had their eye on the Jerry Peak area?

I've not ever seen the original map that the Greater Sawtooth Preservation Council put together for the park proposal; but I know the White Clouds, the Boulders, the Pioneers, were all part of that, but I don't know if it went that far east or not.

But the first I was aware of it was when the conservationists were doing what was called "Alternative W," for "wilderness," when the Forest Service and BLM back in the late '70s, early '80s were doing their land management plans. And then it was always included in our proposal for wilderness.

At what point was it decided to include these lands in this legislation?

Simpson’s first CIEDRA versions had that in it. And the first CIEDRA versions were pretty tough to swallow, because he had huge conveyances of public land to private interests, and he had a lot of micromanagement trail language; but, then, he also had some very good land allocations. And, you know, folks like myself kind of sucked it up and kept working on it because we wanted that prize of what Jerry Peak was going to be. Because the idea of having that broad swath of country between Jerry Peak, Herd Peak, and the White Clouds as wilderness was a big motivator for us.

One thing you've gotten in Jerry Peak is that you've got this transition, this country from willow, aspen, sagebrush, grass, to forest to above timberline. And that's the kind of habitat you want to protect in Idaho. It's diverse. It supports a lot of different wildlife. It supports clean water. And it's a diversity that the wilderness system in general strives to get now.

About 24,000 acres of the new Jerry Peak Wilderness is BLM land. And it was formerly one of four wilderness study areas in the region. The acreage, at least from the BLM's WSAs totaled over 155,000 acres. So was this a good tradeoff? And how do you personally feel?

I personally don't look back and regret it at all. I feel it was a good tradeoff. Part of the thing is because of the connection to the White Clouds. I think the diversity in the areas that did get wilderness is higher than the areas that weren't wilderness. We cut across the wilderness release threshold with the Owyhees. You know there was 250‑some‑thousand acres released down there.

It's always been a give and take with wilderness. I mean, anybody who thinks you're going to go into wilderness and get everything you want, has never seen a wilderness bill happen. So we've kind of got our antibodies built back up now. We know that's the way it's going be.

And it's always been a tradeoff, whether, you know, pieces were left out of from the last version of CIEDRA to what went through the final part. That was probably harder for us than the release of these WSAs that had been released and kind of been on the chopping block, if you will, since the early versions of Simpson's efforts.

The decision as needs to be made when we find places in Idaho that we want to be left wild. I mean, the decision as to protect the wild nature of the place, the primitive nature of it is a conscious one. It just doesn't happen. If you don't make that decision, if Idahoans don't make that decision, then we lose it.

We've seen through the decades, if you're interested in wild character, you've seen the dramatic increase of motorized vehicles, of mountain bikes, whatever, the places that we don't make that decision of wildness is important will be lost.

And this is what we gained, we found another place in Idaho - and, you know, despite the critics, there aren't that many of them - where folks who come together and say this place is as good as it gets, and we want to keep it this way, we want to share this with people coming after us; that there's nothing we can do here to make this place better other than try to protect this character that is right now, as we've enjoyed it.

So what was lost?

What did we lose? Well, you know, we lost the whole release question of some places that won't be considered for wilderness anymore. Again, every bill for Idaho has had those tradeoffs, whether it involves jet boats or airstrips, or whatever, mining claims, that's just the process of doing business with wilderness legislation; you make those tradeoffs. At the end of the day, you hope you've made good ones.