Idaho Headwaters

We are a state rich in rivers. And the waters that feed those rivers—Idaho's headwaters—are truly some of the West's sacred places.

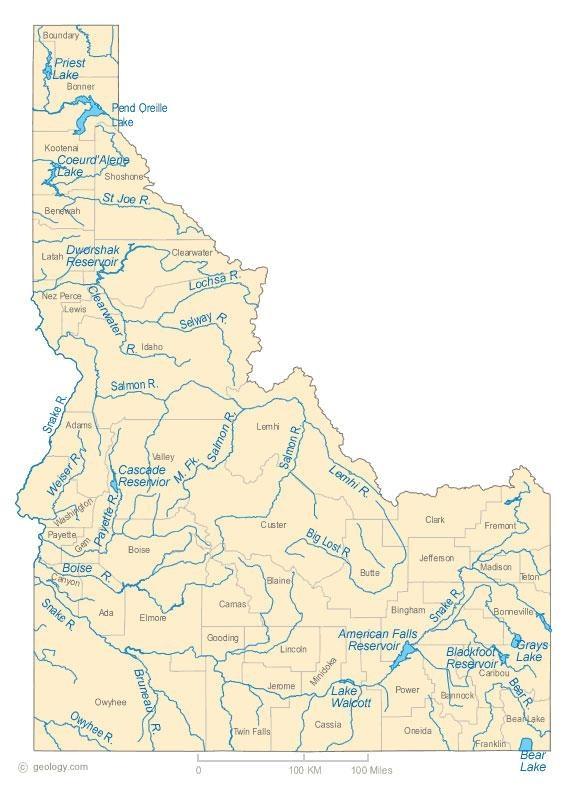

In this hour-long program, we pay tribute to the hundreds of miles of small streams that transport water from the upper reaches of the watershed to the main part of a river. Headwaters help determine the character of major rivers, like the Snake, the Salmon, the Selway, the Boise, the Owyhee, the St. Joe; and in turn those rivers help define Idaho and the West.

Located in some of the state's most beautiful, hard-to-reach places, "Idaho Headwaters" reminds us what it is that's worth protecting in this world of ours.

Idaho's headwaters are truly some of the West's sacred places.

What Rivers Mean to Me

In Hermann Hesse’s book Siddhartha, the river becomes a metaphor. "But today he only saw one of the river’s secrets, one that gripped his soul. He saw that the water continually flowed and flowed and yet it was always there; it was always the same and yet every moment it was new."

When I visit Celebration Park, I am reminded of the Snake River’s history and its newness. The river was here when the petroglyphs were being created, when the first people settled and hunted in the river valley. The Snake River has seen thousands of years, and yet it is still here today, for me to me enjoy. I love the reflections of the setting sun, the golden hues and tones signalling the end of another beautiful day in Idaho. I love the surrounding farmland and the Owyhee Mountains overlooking the river. I love the “modern” bridge that has only been around for over a hundred years. And I love that this park, along this river, is just one of many places in which we young humans get to enjoy the nature that has been around for so long.

For the river, there is no past, or future. There is only the present, only now. And when I visit the river I am reminded that I, too, only have this present moment.

I can’t remember a time when I haven’t been drawn to water. The earliest time I recall was when I was around four years old and we were living in Ketchum at the time. My sister took me to the river to fish. Apparently I caught a good sized trout, because I remember my sister proudly taking me and my fish around to show all the neighbors.

I love to go hiking and wandering with my two hounds. If there is water to be found, we find it and plan our hikes accordingly. Hence a lot of our wanders are in the canyon along the Snake River, near Twin Falls. This stretch of the Snake River is second to none as it is cradled in the magnificent canyon of basalt and rhyolite, formed partially by the great Bonneville Flood approximately 14,500 years ago.

There is a place that I frequently wander to that gives me my ‘water fix’. I can get there in a matter of minutes and often am the only one there. It is the stretch of the Snake River that is known as “Auger Falls”. The name derived from the corkscrew action of the water as it drops several feet in elevation. You hear the rush of water before you see it.

Not everyone would see the same beauty that I see, nor feel the energy and mood enhancer that I feel, but there is a place that I go, that without fail, puts a smile on my face and where time stands still.

The Jim McClure-Jerry Peak Wilderness is as wild as the depths of the Frank Church but lacks the thick forests. My favorite river is the East Fork of the Salmon because its tributaries lead to beautiful and exciting places in the White Clouds. The photos are of beaver dams on one of these tributaries, Herd Creek, and a pond at the lower end of Lake Basin.

To me wilderness is where people can see the land as it was before European settlers came. People can enjoy the scenic beauty – the cliffs, waterfalls, wildflowers and the alpenglow. They can meet deer, bear, moose, antelope and even rattlesnakes. There are no motors or speeding vehicles. Wilderness is just you, your companions if any, and the land. It is a place where you can confront and overcome the biggest danger in your life – yourself.

Just like in a good movie or a good song, the lead-in is critical to the rest of the story. Headwaters are that lead-in. They begin the story, they feed the plot line, and give life to the entire production. The beginnings… and then come the falls, the lakes, the rapids, the meanders and the life that all of earth's creatures require for mere survival. It’s the source of travel for the Steelhead and the Salmon and home to my friends, the Trout.

For me they have been mystical places amongst the crags that call me like the Siren’s song. The insatiable desire to find them and behold the end of the quest has haunted me throughout my life. When I find them, I have a curious sense of togetherness. To drink of the cool clear liquids of a headwaters spring is divine.

And then to float along in a boat miles below, knowing where it all came from, is gratifying. Headwaters give me my places to love, and they provide for me. Without them I would not have the life I do.

What do you see when you look at the water? Your reflection? Looking on the outside…. or inside… or beyond, to the whole of what and where you might be. I don't think it matters where you might be or what might spark your reflecting. If you're getting away from it all just to enjoy the day, or if you're actually in search for something.

It's a feeling of freedom. In this place you can't feel anywhere else. Once you stop and look around and see where you are, how far away from it all, it's hard to explain unless you're out there. You don't need to understand, but I think you should probably try it if you haven't.

Whatever you see, whatever you feel is yours. It is up to you to discover. Find it, live it, share it. Things can happen in the blink of an eye, and what you know, could be different forever. Try to see those reflections everywhere, in your surroundings, yourself, and others.

First there are creeks and then there are rivers. Idaho has an abundance of both, but my heart belongs to a creek called Deep Creek in the Owyhee Canyonlands.

In the rolling southwestern Idaho sagebrush steppe, it is a surprise to come upon the deep canyon complex edging the many forks of the Owyhee River drainage. Sheer canyons, as deep as 1000 feet, run for miles across the desert floor. In late April, they are a rush of water and beckon kayakers and rafters to ride the spring runoff.

My relationship to this complex began while hiking and camping in its many drainages. Many of those trips were memorable. I photographed Idaho Department of Fish and Game biologists when they reintroduced California bighorn into the complex by helicopter in the winter of 1985. By then my husband, Ed Robertson, and friend Brian McColl had heard of a creek in the system a few kayakers were calling "beautiful"…Deep Creek. Ed and Brian wanted to canoe it. In 1989, I ran the shuttle and photographed the canyon rim while Ed and Brian were probably the first to run the creek in a canoe. Shortly after, I accompanied Ed down this stunning creek. Its red rhyolite cliffs are home to bighorn, cougar and bobcat. Its water is home to trout and waterfowl. Its solitude, rich wildlife, other-worldly geology and spring water flows drew us back again and again. Very few people have ventured down the 30 plus miles of this creek. Its pristine wildness and rugged beauty makes Deep Creek my favorite creek in Idaho.

Rock Creek is the headwaters of my youth, middle age and hopefully old age! Starting in the South Hills south of Hansen, Idaho. Rock Creek is gracefully fed by snow run off and springs. This creek has provided endless hours of enjoyment for many generations of my family and other countless families. It has provided food and shelter for pioneers, Indians, animals, insects, birds, fish and reptiles. All seasons are my favorite … impossible to choose just one. This creek meanders through the Oregon Trail, farmland, and now a growing city until it releases its flow into the mighty Snake River. The pictures are of Rock Creek in the fall and my 18 month old grandson who is learning the fine art of catch and release fly fishing in the exact spot where his Daddy learned. The native brown trout he caught that day with the help of his Grandpa was reluctantly released to catch another day in these headwaters of Rock Creek to continue to flow into generations to come.

John Muir wrote that "Rivers flow not past, but through us; tingling, vibrating, exciting every cell and fiber in our bodies, making them sing and glide."

That may be true, but for most of my life, I've been a lake guy. Who ever heard of hiking 10 miles to get to a river? But a nice mountain lake, well, that's another story!

And yet, and yet… over the years I've come to better appreciate the sparkling kinetic energy of the streams that flow into and out of those mountain lakes. And being able to follow a good sized river like the Middle Fork of the Boise back to its headwaters, and to see the transformation as one climbs higher into the Sawtooth mountains - that's a pretty sweet experience, made even sweeter by having Spangle Lake as the headwaters of the Boise River.

I suppose it was when I took up rafting that I really came to appreciate Idaho's amazing rivers. Being able to travel for 100 miles for an entire week on the Middle Fork of the Salmon River, through country that is constantly changing, and all the while being forced to pay attention to Class IV rapids that are quite capable of seriously hurting you - well, few states offer such an exhilarating experience.

I am grateful for Idaho's powerful rivers, grateful that so many headwaters reside in protected lands, and I am always grateful when a mountain lake is at the end of a 10 mile hike.

Dry Creek's headwaters originate near the slopes of Bogus Basin. Driving to the ski area, you unknowingly cross over a bridge spanning an unmarked section. Most years, the water does not reach down to the Treasure Valley. It is absorbed into the granitic soil of the surrounding Foothills.

Dry Creek is best seen early and late in the day, when the Boise Foothills reflect glancing sunlight with magical qualities. It's a go-to place for hikers, joggers and mountain bicyclists escaping the city's hustle and bustle for a few hours. And surprisingly, the upper reaches of Dry Creek's pure water also support a small population of endangered red band trout.

So why does the diminutive Dry Creek matter when Idaho has so many great rivers? For me, Dry Creek is important because of its unchanged connection to Idaho for the past 150 years. It's one of those small gems that help make this place home.

Most days, because it’s near my house, I walk beside one of the reservoirs that comprise most of the “managed” Snake River. Reservoirs and their dams feel like graves and their headstones to me. On days that this makes me sad, I stare out over stasis (a thing no river can endure and still be a river) and send my mind upstream to rugged nursery peaks where, at that exact moment (moments being much larger things than I sometimes credit), the Snake and all my beloved rivers are being born.

Rivers are the life blood of our land. Even when you look at a map, with the blue lines it reminds me of the blood veins in our bodies that give us life. Our rivers give us all life.

My favorite river in Idaho is the Snake. The Snake is 1,078 miles long and is the largest tributary of the Columbia River. The Snake starts in western Wyoming, and runs through four States: Wyoming, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington.

As a photographer, I find the Snake one of the most beautiful to photograph. I have photographed it from Yellowstone to the Pacific Ocean, and today I am still looking for untouched areas in Idaho along the river to photograph. It supports some of the most wonderful scenery of waterfalls, wildlife, and outdoor activity of every kind.

The River supports wildlife species, some of which I have never seen anywhere else. I have witnessed wolverines, gray wolves, grizzly bears, moose, elk, deer, all kinds of birds, and recently a porcupine I had never seen in my life. The aquatic life in the river is even more versatile than I ever thought, but being an angler as well, it is my favorite for good-eating fish. It is known for all kinds of trout, bass, sturgeon, crappie, and even good eating catfish.

Every trip I take along the Snake has held a new surprise for me to view and share. I am proud of the Idahoans that do all they can to take care of all our watersheds, and take this opportunity to thank you all.

A smell of wetness sitting beside a serene river, watching wildlife brought there by water. Light reflections off liquid silver. Visions of water snakes, snails and dragonfly tails. These thoughts come to mind when I think of rivers.

Roaring loud, a river provides an adrenalin rush for me as I paddle through. A river has moods -- and influences mine. A river speaks to me of primitive times when the land looked different, and the river carved itself into rocks that became mountains. Rivers laugh over colored rocks for me. They hide fish waiting for my fly. Rivers draw me, like paths not yet traveled. What's around the bend? I must see!

Looking down from high up on a cliff, the river looks remote and safe, but I will never underestimate its power and relevance. Rivers warn of floods, changes in climate, and of futures without them.

My home river is the Payette. It winds down, across and through many small towns in Idaho. I spend a lot of time in the creek below my house. Eventually it winds up in Squaw Creek and then into the Payette. I feel connected to the earth because of the creeks and rivers flowing by me. They are the silver spider webs flowing on the land to connect all elements, all peoples, providing sustenance as they whiz or trickle past. Stand by one, feel the energy. Renew thyself.

Rivers mean life.

Paradise Creek runs through what used to be called "Hog Heaven" (now known as Moscow, Idaho) before joining the South Fork Palouse River and then on and on to the Columbia and the sea. It's a dirty creek, best described as chocolate milk in the spring floods, grows only a rare trout, mainly minnows and leaches. It's beautiful, though. Beaver slap their tails. Deer and moose stop to drink, and herons wade, spearing speckled dace.

This Idaho crick inspired teenage me to restore rivers. It brought together city hippies with visionary farmers and strong-backed students to nurture a ribbon of riparian forest through our subtle valleys of brown loess hills. It wove together a patchwork of conservationists and academics, from the prairie fanatics to the no-till drillers and foresters to PhD students studying bumble-bees. A copse of quaking aspen, a black hawthorne grove -- some native willows and a few wildflowers clinging to the edge. Using hydrojets, dibbles, and hoedads, we planted thousands of red-stem dogwoods, coyote willows, camas lilies and tule reeds. Things grow slowly along Paradise Creek, and it takes a lot of care to keep young saplings clear of weeds and protected from voles and beaver. Once they do grow, they shade the water, feed the stream, clasp the banks, and nurture nests in their branches.

By offering us the redemptive grace of creating a better future, these headwaters instilled in me a passion for restoration ecology.

Interviews

Jim McNamara is professor and Chair of the Department of Geosciences at Boise State University. This interview was conducted by Bruce Reichert in the summer of 2015. Topics included the Boise River and Dry Creek, whose headwaters is near Bogus Basin ski resort.

Can you put Idaho into some kind of perspective in terms of headwaters and rivers?

The first point is that we have a lot of river miles, more than most states outside of Alaska. And most of the headwaters of those rivers are in protected or low population areas up in the mountains. It’s a good thing because the health of rivers downstream depend on the health of the headwaters upstream.

We’re standing by the Boise River and this is one main channel, you know tens of miles long to the Snake, but if we were to go up in the mountains and walk up every stream, you’re going to walk a lot farther. There’s hundreds of miles of these headwater streams; every little basin has a stream in it; and if we add up all those river miles, there’s a lot more length in the small streams than there are on the big rivers. We look at the large river here and think, well, that’s the Boise watershed; but the reality is the cumulative length of the headwater basins exceed the main river length. And so they’re important areas.

One thing that is unique is just the large percentage of the state that is in protected areas, whether it’s state or federal or local or just happens to be unpopulated. That’s where the headwaters are; and so the existence of headwaters in those protected areas really makes it a special place to live, and it keeps our rivers healthy and clean and fun to be on.

How would you define the term "headwaters"?

I would call headwaters a primary collecting basin where there may be a stream in it, there’s no other tributary or just a few small tributaries, and then they accumulate to bigger and bigger streams. And so most of the headwater basins or headwater areas tend to be up in the mountains at least for the rivers in Idaho, but we can have small tributary headwater basins along an entire river length.

Can you say that headwaters determine the character of a river?

Yeah, the health and character of the headwater streams definitely impact downstream. If we look at the Boise River, there’s sediment in there that fish rely on for their spawning habitat, and the sediment sources are up in the mountains in the headwaters.

What is unique about the Boise River from a hydrological point of view?

We’re standing here in the middle of the largest city in the State along the Boise River, and if we had a fly rod, we could catch a trout. And there are very few cities that can harbor trout in the city because trout require very clean, fresh, cold water. And the reason we have that is we’re so close to the relatively pristine headwaters of the Boise River Basin just upstream from here. There’s not many cities that have that.

What’s interesting about the Boise is that there’s such a distinct break between what we’ll call the urban wildland interface, the reservoir system, and above that is a lot of wilderness and low population, low use land, very pristine. So it’s a river that experiences the extremes. It’s heavily managed and the water down here is cleaned and used, whereas upstream we have the opportunity to see rivers and streams in their natural states.

Near the headwaters of the Boise, you can get to the headwaters of several rivers up in that same area, and then as you come down the Boise, we have a working operational water management system providing water to the bulk of the population of Idaho; so it’s a huge economic driver of the state.

When hydrologists get together to talk, what do they talk about?

What dominates the conversation is what is happening to the snowpack. It all depends on the water supply. Is the snow melting earlier? Is there more or less precipitation? What’s the temperature doing? For example, this year is a big El Nino year. What happens in the Boise River isn’t real straightforward, but we’re expecting more precipitation, so the skiers are excited; but we also need cold. So we don’t know if more precipitation means more snow or just more water. And so as we’re hanging out chatting amongst our hydrology friends, that tends to be what we talk about: what’s happening with the snowpack?

How would a changing climate affect the Boise River?

The primary affect would be on the timing of stream flow. If you look at what’s called a hydrograph -- a plot of stream flow versus time -- it’s very big in the spring when the snow is melting; and then it recedes to these low summer flows. How low the flow gets and when that occurs is really dependent on the timing of that snowmelt period. So if we keep the total amount of precipitation the same, but it turns to rain, then we’ll get probably more stream flow in the wintertime because its not being stored in the snowpack, but then what happens is that it’s not going to be available in the summertime.

Explorer and engineer John Wesley Powell, when he wrote his 1879 report on water in the west, favored defining state boundaries by watersheds. A good idea?

I think it’s an interesting idea, and he did that based on the idea that I think he estimated that maybe two percent of the land in the arid west is actually useable for agriculture; of course, we’ve far exceeded that. So I don’t know, if we had split up states by watershed boundaries, right now we trade water amongst states and we have agreements. It would be interesting to see if we were actually physically defined by our water resource area what would happen? I like the idea, but it seems that may lead to more conflict than we already have.

Let’s talk about Dry Creek, above Boise. Who cares about a small creek?

The last 15 years I've turned Dry Creek into a hydrologic laboratory. Scientists are interested in how water gets to streams; where does the water go when it rains? Believe it or not, there's a whole discipline of science that spends a lot of time trying to figure that out.

It's called "Dry Creek." Ironically, this is the only creek in the foothills above Boise that does flow year-round; the other ones are actually dry. And if you were to go farther down Dry Creek, it would be dry, as well, but up here at the source, in the headwaters, the water is emanating from some springs in the granite, just below the wall that you might be able to see behind me. And so there's an aquifer in the fractured granite that, for one reason or another, is in this creek and not the ones around it, that retains the snowmelts, and slowly it releases it through the summer.

What have you discovered in your studies of Dry Creek?

We're actually more interested in the watershed overall. So some of our studies have been related to snowpack. And so we have received some funding from NASA; they like to monitor snow from space, and they need people on the ground to figure out how much snow is actually on the ground. And so we'll do some studies to investigate the distribution of snow in the landscape.

But then that snow melts, and then we become interested in things like, how does the landscape meter out water through the summer? It turns out that because this is one of the only streams that flows year-round, there is a population of redband trout in Dry Creek. And so we're looking into, how do they survive in these low-water years as the stream dries up? It contracts upward; whereas, nonspring-fed streams will dry downward. And in those streams, the fish may move downstream to find refuge. Here they continue to move upstream. So we're looking at kind of the geologic and biologic controls on that.

Essentially, wind, rain, or snowmelt enters the watershed; ultimately, it either goes to groundwater recharge in our aquifers below or streamflow or evapotranspiration. And for hydrologic forecasting, the modelers need to know how to predict that, and so we do field studies to describe how that what we'll call -- "hydrologic partitioning" -- happens.

This year is a drought year. How is that affecting Dry Creek?

We've been monitoring Dry Creek for approximately 16 or 17 years. And for the first 10 years I'd never seen it go dry. Although there's water here, when we go downstream, there's no water in the stream. And I used to say, "Oh, Dry Creek flows year-round." But then in the last 8 years, I think maybe 3 or 4 of the last 8 years, we've seen it dry up. And that drying kind of propagates up through the summer.

And so back to the fish; my colleague at College of Idaho, Chris Walser, is trying to document how this population of redband trout survive in these dry years. And they don't survive very well during these dry years.

Do all headwaters of Idaho's streams have similarities?

Headwaters are similar in that, if they're flowing year-round like this, they're coming from a subsurface source, usually in some kind of bedrock emanating as a spring.

Have you been able to document what Dry Creek means to this part of the world?

Having supervised 40 master's theses in this watershed, I would like to say, yes, of course, I know a secret to this place. The reality is there's so much going on here that what we do is we study the relationship between water and kind of human society or ecological questions. And so I could tell you 40 different answers from 40 different theses about the specific questions they asked; but the truth is, I don't think there's anything particularly interesting about the site.

What we like to do is use it as a laboratory to answer more general hydrology questions. If we were just studying Dry Creek, then my few students and I would be the only ones on the planet that cared. And so when we write our studies up, we try to think, what can we learn about semiarid regional hydrology? And so we try to generalize it.

I work here because my office is down the hill, and I have colleagues around the country who do the same thing; they study their backyard watersheds. And then we get together a couple times a year and talk about how our watersheds work; and we get an understanding about the variability of hydrologic processes in different mountain environments.

Are you optimistic about the future based on what you're seeing?

My personal observations are that the dry years are more frequent, and it's not just climate change, but human population growth, definitely. You know, both conditions are happening, whether it's good or bad, and they do stress these water environments. The snowpacks in the western United States are diminishing, and so changes certainly are occurring.

That's what's happening. Now, is change good or bad? Well, change is change. And the streams have changed. You know, landscapes have changed. It's all a matter of perspective.

The whole watershed is a kind of a patchwork of different land ownership. There's federal land. We're currently on Forest Service property. There's also some Bureau of Land Management, property, and there's a lot of private property. And because of Dry Creek is kind of a unique place, where we have a conifer forest down to the high desert, hiking up here is becoming more popular. And so there is an interest in preserving Dry Creek for its natural heritage.

And recently the City of Boise did acquire some easements with the private property owners to improve the trail system to make it part of a formal city trail system.

What’s your vision for Dry Creek?

My vision and goal would be that, yeah, this becomes a protected area to enjoy for its natural resources, for its aesthetic beauty. It's just a nice place to be. Our office is about 17 miles by road from here. It's going to be 95 degrees in Boise today, and we're sitting up in the shade of the forest, and it's on the way to the ski area, and so it's just a nice place to get out and work. I didn't decide 18 years ago to make this the focus of my career, but it certainly has.

I have a network of about 20 or so stations logging meteorology and hydrology data. And there aren't very many places in the country operated by universities that do that. And so the site is becoming, in the hydrologic science community of academics, a well-known site. And people ask for our data maybe to test their models, because not a lot of people have the data that we have to validate the models.

That's what keeps us in funding. Historically, the federal government used to operate what they call "experimental watersheds," but funding is being directed other places. And so long-term hydrologic datasets are of immense value to people who are developing forecasting models.

Jennifer Carpenter is acting chief of the Yellowstone Center for Resources. She also spent a number of years in Grand Teton National Park, so she is very familiar with the Snake River and the entire ecosystem. This interview was conducted by John Crancer in July of 2015 in Yellowstone National Park.

Where does the Snake River begin?

The source of the Snake River, the headwaters of the Snake River, if you will, begins right around the border between the Bridger-Teton National Forest and Yellowstone National Park about -- three little streams come together to form the headwaters of the Snake River, the source that flows into Bridger-Teton National Forest and then up through Yellowstone National Park to the boundary with the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Memorial Parkway.

What kind of topography is the Snake River flowing through in Yellowstone Park?

It's very mountainous terrain, it's a very remote location, it's wilderness. Essentially, within the Bridger-Teton it's designated wilderness, and within Yellowstone National Park it is recommended wilderness, so it's very remote terrain. Very little use goes on at the source location at the headwaters area. There is a trail that goes back there, some back-country users hike back there, but, generally speaking, it's a pretty remote location.

Talk about the two primary watersheds that flow from the Continental Divide within Yellowstone National Park. How waters flow to two different oceans from this location.

It's interesting in that Yellowstone does have the source for two major watersheds, if you will, within that general geographical area. So I've talked about the Snake River and the source right there that makes up the Snake and flows to the Columbia River which flows to the Pacific Ocean; while the Yellowstone River, which is an iconic river, starts out in the general area, flows into Yellowstone Lake and then flows northward through the park and then up through Montana, where it meets the Missouri River, and then flows to the Mississippi, which then flows to the Gulf of Mexico.

How much water is coming off the west side of the Continental Divide? We saw so much water and so many streams everywhere on the west side that's feeding the Snake.

There are many, many tributaries to the Snake that flow off the west side of that Continental Divide, and that's why this act is so important, in that it protects those tributaries in the main stem of the Snake River in perpetuity, if you will, for future generations to use both recreationally and for other water users downstream.

Tell us about the Snake Headwaters Legacy Act. What waters were protected by and how many miles of those are within national parks?

I believe it's about 414 total miles were protected by the Craig Thomas Snake Headwaters Legacy Act. Within Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Park and the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Memorial Parkway about 99 miles of tributaries and main stem are protected under the act. Within Yellowstone National Park, of course, the Snake River, itself, and then the Lewis River Channel between Shoshone Lake and Lewis Lake, the channel there that it goes between those two lakes. And then Lewis River that comes southward from Lewis Lake to the Snake River is also protected in Yellowstone.

Within John D. Rockefeller, so where it meets the boundary between Yellowstone and John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Memorial Parkway, the Snake River flows into the JDR -- as we call it -- and flows southward where it meets the mouth of Jackson Lake. It then -- that protection stops at Jackson Lake, which is managed by the Bureau of Reclamation, and then once it leaves Jackson Lake Dam, the protection, then, gets picked up right there at the dam and flows southward through Grand Teton National Park.

There are several tributaries, within Grand Teton National Park, of the Snake River that are also protected that includes Pacific Creek, the Buffalo Fork River, as well as the Gros Ventre River, which is south -- in the south end of the park, which flows from the Bridger-Teton National Forest and the National Elk Refuge toward the Snake River. So a pretty wide, expansive area that comes down off the Continental Divide that feeds the main stem of the Snake River.

Why was this act important?

It was extremely important. It's essentially, you know, the headwaters are the source of the Snake River which, if you think about, is the main water source for many, many, many users, be it, you know, wildlife, fisheries, birds, vegetation, as well as human users and agricultural uses and Native American cultural uses. So, essentially, it's the source of all of that water that eventually makes its way to the Columbia River and the Pacific Ocean. So it's extremely important for us to protect the headwaters and the source of that watershed.

Why do you think it took so long? I mean this is pretty late in the game, the park was established a long time ago.

Absolutely, yes. And some would say, well, the headwaters are already in a protected area. This just affords another level of protection. It keeps the free-flowing condition of the water. It keeps the water quality secured. And it keeps those outstandingly remarkable values of the designated segments secured in perpetuity. So it's extremely important, I think, to add that extra level of protection just so we can ensure for future generations that it will remain protected.

What makes the Snake River such a unique waterway? Why is this an important conservation story?

It's quite amazing to think about the source as being just three little streams up in a mountainside and how that eventually all comes down to the big Snake River that runs through four states, essentially, and how important that is to so many users, both ecologically speaking, as well as, agricultural, industrial, municipal, and Native American cultural uses.

So I think it's an amazing story, conservation story, if you will, for the protection of that waterway that's so important to so many users across so many states. And I think that it's a conservation win, I think, to have the Craig Thomas Act be implemented.

Did you have any reactions when the omnibus bill that included this act passed?

Oh, I just thought it was fantastic because not only did it protect the Snake River, but many, many, many other rivers within the general omnibus act were protected and designated wild and scenic. So I think it was a landmark piece of legislation that offered a lot of conservation value and protection for rivers and streams throughout the Western United States.

We really want to bring people close to nature. And we want to do it in a way that protects the landscape but also allows them to have that wilderness experience. And I think by protecting these river and waterways, I think that does allow us to sort of bring those two worlds together and create those wilderness experiences for visitors in a pristine landscape.

Maybe just a personal question. What do you enjoy about working in this park?

I just love the greater Yellowstone ecosystem. It really is close to my heart. I really found a home here. And being able to serve in a conservation capacity, to be able to work towards protection and conservation of the area and serve the visitors that come to experience the wildness of this place is really meaningful to me.

I come from a park service history, a park service family, if you will, and so I'm continuing on that family tradition. And it's truly meaningful to me to know that I'm participating in not only the protection of the landscape and the earth and the ecosystem, but I'm also helping share that experience with visitors that come to the area.

Todd Shallat is the director of the Center for Idaho History and Politics at Boise State University. He is also the editor of the recent book, “River by Design,” about the Boise River. This interview was conducted by Bruce Reichert in the fall of 2015. Topics included the Bureau of Reclamation and the Boise Project.

Put Idaho into some kind of context in terms of how it has dealt with water and rivers, compared to other western states. Do we stand out in any particular way?

In the 1950s a great historian, Walter Prescott Webb, wrote a very controversial article, talking about the Great American Desert. He took that term from the 1820s, and he reapplied it.And politicians and opinion-makers in Idaho were very, very upset to be included with Nevada and Arizona. They argued that it was really a different place.

But if you talk about the high desert, what the historians are talking about really kind of rings true, because really what we're talking about is the Intermountain West. And they have certain commonalities, and water is one of them. So because it's dry and people live in sparse settlements, and because of that, it really just influences everything: our mobility, geographic and social. It influences our laws, and it also influences the way the federal government manages us, which brings us to the Bureau of Reclamation.

One peculiarity of Idaho is that we have more water than the rest of the high desert. We're an exporter of water, in terms of hydropower and other things. Idaho probably has more water per capita usage than anyplace in the world, at least anyplace in the United States, for sure, and especially if you're looking at the Boise Project.

So you're talking about a situation where the consumptive use goes down, but the amount of water we use goes up. It's a highly concentrated type of water usage. It's a type of water use where urbanized gets charged by the gallon, and farmers get charged by the acre-foot. So it is much different than Nevada, than Las Vegas; it's different than the Central Valley of California.

We assume Idaho's much like other places, but it has its own unique character. For example, when I first came to Idaho there was a big movement to start calling Idaho part of the Columbia Plateau. It's like that made sense with geologists. When they talked about those kinds of formations and the rocks, they talked about the Columbia Plateau.

Then in the 1980s, they start calling it the Snake River Plain. And they started seeing Southern Idaho as a different geology, one that's filled with fissure volcanoes, and then they started talking about the western plain and the eastern plain. And so the analysis got more specific, more local.

And so now there's a movement to call Boise and this part of Southern Idaho as part of the Great Basin. And in some ways it is.

You just finished a new book, River by Design. What did you discover?

So annually I do a sort of community research project, where I invite professional writers to work with my honor students or the best students that I can find, and we'd see if we can produce a book in a year.

River by Design was sort of a tour of the Boise River from the headwaters to Parma. And the premise of the book is that when you look at the Boise River from the air, what you're seeing is not necessarily a natural system, and it's not just engineering either. If you want to understand the way the river looks -- why it's curved here, why it's slack there, why it floods here -- you need to understand how culture, the economy, and engineering overlap.

We tried to look at these places in the river that were engineered, highly engineered to look natural. They were engineered to look like nature, but never the nature that was here originally; the nature in our head, the nature that it needs to be.

Tell us about Diversion Dam on the Boise River.

If there was ever a place in the West that was socially constructed, that looks like it looks because of -- not just because of engineering -- the engineering was path-breaking; not just because of the politics -- the politics was path-breaking, as well, the Bureau of Reclamation; but also, you know, financing, and, also, it's pure Idaho. It's western.

In order to understand why it looks the way it does, why it's physically engineered the way it is, and why the river below it looks the way it does, you have to understand a little bit of its historical story that explains its engineering, that explains the way in which we regard it today.

We value it because it looks like nature, the river below it, but not like nature looked before the dam was built, but like nature that's framed for us by Rembrandt in the great landscape paintings, as the meandering stream through the tall bluffs, just forested so that the cliffs show so that we get this feeling of "sublime" when we see this landscape. And it's engineered purposely to elicit that. It has a certain -- architecture has a "parkitecture," if you will.

A famous book was written about it called Angle of Repose, by Wallace Stegner, which won a lot of awards. And in Angle of Repose, the backdrop is the building of the New York Canal. And it tells the story of a fictional character based on this great mining engineer, Arthur Foote, and his wife, Mary Hallock Foote. His dream was to have a giant mining project where he would take water from the Boise River down to the Snake River as a mining enterprise for hydraulic mining.

As the program evolved -- he started in the 1880s -- he started to see the possibilities of a canal network, and he mapped it out; and that's the Boise Project. More or less it follows the blueprint that Foote laid out.

And what Foote noticed when he looked at the Boise Project is that the desert was not necessarily dry. We think of deserts as being barren. We think of this as being wasteland. But, in fact, deserts often flood. And when they flood, maybe once every five years or ten years, the water naturally trickles down certain crevices and down chutes and sloughs; and where the water naturally goes by gravity, Foote realized that that probably would be a successful engineering project. Engineering, when it works with nature, is likely to be more efficient than when it is actually defiant.

So it is that he mapped out with New York investors this project. And he built the New York Canal, which became the Boise Project. In 1902 the Reclamation Service was formed, as part of the Department of Interior. And it was formed as a way to break land monopolies, the way that the progressives saw it.

Teddy Roosevelt thought that the biggest danger to American society was what he called "trusts," land monopolies, that would so control the West that the individual freeholder, the farmer, couldn't possibly get a break. He'd have to compete with these huge operations and would be crushed.

And so Teddy Roosevelt saw the Bureau of Reclamation as something that would help right the balance, because the water would be limited. He saw the Bureau as limited to a farm of 160 acres, or 320 acres for a husband and wife. So that was very much a part of the engineering on how they sold it to the public and how they sold it to farmers.

So that was the original story of the Boise Project. Then Diversion Dam was built in 1907. When it came on line, it supplied the New York Canal. The New York Canal first began as a private company and then like an irrigation district. The source of water was not always that reliable. The dam washed out a bunch of times; it had a small diversion dam here, a rock dam, and it flooded out. And it wasn't that reliable.

And so when the Bureau came in with federal financing, they lined the canal, and they built the dam, so that had a good diversion, hence the name. And then three years later, they added power. And with the hydropower, they built Arrowrock upriver, so that's why the Diversion dam has a powerhouse.

So it is really a significant thing in the history of America, maybe even in the history of the world in terms of our water, in the sense that it's really the first project of the Bureau of Reclamation, the first federal reclamation project. It started simultaneously in a couple of places, but the Boise Project was already going, and so it became a kind of test case.

Secondly, it put the Bureau of Reclamation into hydropower, which is going to be a huge thing later on.

And, thirdly, their dams that they built were so incredibly massive; they were the tallest in the world. They kept on breaking records for height, one after another after another; they were just enormous.

Arrowrock Dam, when it was completed in 1915, was the highest dam in the world, the tallest dam in the world. And it was also the very first what they call a gravity-arch dam, the very first concrete, high-rise concrete dam.

What was the purpose of Arrowrock Dam?

If the purpose of a dam is to impound water, then Arrowrock is an enormous success; it impounds water. It can't be moved short of an earthquake, probably. But that was not the purpose of the dam.

And so I looked at the Boise River, and Idaho water generally, as a really good example of what some people call "revenge effects," the revenge of technological systems, the sense in which technology sometimes plays a judo trick in which it flips the result through unintended consequences.

So here's what I mean; if you build a dam for flood control, and it kills fish, that's unfortunate, but that's not a revenge effect. A revenge effect would be if you build the dam for flood control, and it causes flooding or it increases the flood risk; that would be a true revenge effect. That's the classic example of Arrowrock and Lucky Peak.

The Boise Valley is in much, much more danger of flooding at a much higher cost, with much greater consequences because of those systems than they were before, for obvious reasons; people crowd the flood plain and are subsidized to build in dangerous ways.

But here's the point of the revenge effect: So Arrowrock was the first really big dam on the Boise River. There's about five now, depending on how you count. And they all have different stated purposes, but the primary purpose for all of them was to promote family farming. And it's defined very well in the law. You know, they're talking about small acreage farms. They're not talking about hobby farms; they're talking about commercial farms that could sustain somebody. They're basically talking about farms of less than 500 acres. If you want to bring it up to modern terms, you could say less than a thousand acres. They're talking about that mid-level farm.

Seventy percent of the Boise Project that's irrigated now was irrigated before, by the canals, but it was locked up by companies. And so the Reclamation Service was conceived in order to right that balance.

One hundred years later we celebrate the centennial of Arrowrock Dam. There's all kinds of Bureau historians giving lectures, calling it the Eighth Wonder of the World. And to hear them talk, you would think that dams were an unmixed blessing, that without dams there would be no wealth in the valley; it would be wasteland covered by sagebrush if it wasn't for Arrowrock and the Boise Project -- this is to hear them say it.

One could make that claim, depending on how you would define wealth. But one thing for sure is the revenge effect. Because of Arrowrock and the Boise Project and the system that it supported, water subsidies, farm subsidies, and this larger technological system, the family farm is rapidly disappearing, and the vast lion's share of the subsidy, the taxpayers dollar, goes to support like 3 to 5 percent of those very, very largest.

It's a classic revenge effect.

Arrowrock Dam celebrated its centennial a few months ago.

So this is a wonderful opportunity that we have now that Arrowrock is 100 years old. It's a wonderful time to look back at history. I mean, let's look back at history, but let's not stare, let's not blame people for the way things were. It came about for a reason. But let's also learn and say over the long term what happened to the Bureau of Reclamation's vision, this progressive vision that became something extremely regressive.

And that is one very important reason why Idaho is impoverished. We're not talking about low income for the rich; we're talking about the distance and disparity of wealth between the people that own most of the land and their workers, which in this valley are migrants and are very low paid.

In the 1950s this valley had a lot of family farmers. There was a lot of small-acreage farming done, farms a little less than a thousand acres. And then by the 1970s and the '80s and more recently, the 1990's, the middle sort of fell out. You still had the little hobby farms, and you still had these great huge farms and more acreage all the time in the big farms. But the middle fell out, which was sort of like the backbone of why this system was built.

Any final thoughts about the Boise River?

The Boise River has been engineered to look like nature, but not ever the nature that was here. We don't know what the state of nature looked like on the Boise River because it never froze into a state. It was ever-changing and dynamic. But nevertheless, in order to manage the system, we need a narrative. The agencies cannot function without some sense of stability so that they can plan.

And so what they do is when they look at the history of the system, they tell these two counter stories. One is the one that the irrigators say. They say, back in the beginning of time or back in the state of nature, before civilization, there was a wasteland; it was sagebrush covered with wormwood and just burned and in impassable ways. Engineering came, slowly, in a progressive way and civilized and brought life to the desert and brought the wonderful society that we have right now.

The other way to look at it is the way the environmentalists sometimes tell the story. They say, back in the state of nature this is a tall-grass prairie, there’s antelope running around, the natives were well-adapted to it, living a life of leisure, and then one by one engineering came and desecrated the garden.

And so one side sees Arrowrock as an icon of progress. Another sees Arrowrock as the harbinger of our decline. It’s apocalyptic. And both are based on something very a-scientific, which is the idea that there's a beginning. Progress to what? The climb from where? It's like, without a beginning. So that's why it's useful to go to the headwaters and see the beginning; because the river is like a story. It has a beginning; it has narrative flow; and it has an end.

So let's go to the headwaters and think about where the river begins, so we can see the dynamic, that dynamic that nature is; not a state, but ever-changing.

Steve Burson owns Storm Creek Outfitters with his wife Lorrie and operates in both the Frank Church River of No Return wilderness and the Selway-Bitterroot wilderness. This interview was conducted in the Frank Church wilderness near the headwaters of the Selway River by Bruce Reichert in the summer of 2015.

Getting to your outfitter camp has not been an easy ride.

No, we rode around from Hell's Half Acre, the Divide Trail, so you ride the Montana Divide and then break off to the Selway River-Salmon River Divide. And this time of year it's the only way into this country because of the trail conditions. So a lot of up and down, a lot of pretty precarious spots and things. The snowfield was fun. So we got through that okay. Everybody got here all right, and I could relax once we got the fire going.

It was a long day. You know, we got up at 4:30 to get going, and we got here at 9:00 o'clock last night, so it's a full day. You heard the song, "It's not the years, boys, it's the miles." In this country it's not the miles boys, it's the trails.

Those of us who aren’t used to 22 miles on a mule particularly liked the parts where we got off and walked!

Yeah, and we do that a lot. I mean, we're not cowboys back here; we're mule packers. This is the most rugged country in the Lower 48 right here, especially the Selway. So it's a lot easier on the animals if you get off and walk down. It's easier on your knees and much easier on them. We're in here quite a ways. You know it's a full, full day. If you sore your mule up coming in, you're walking out.

So everything we do we try to do to have the animals have the easiest possible trip and to save them and not have injury at all or just sore. You know, you don't want to sore them up. We've got to use them almost every day.

Your mules are certainly up for the journey.

Thank you. We've been developing; we cull out maybe 10 percent every year looking for better animals. We went back to Tennessee this winter and bought 10 mules. We probably looked at 400 to pick the 10 that we picked. Very, very, good disposition, and then we pack them for a couple of years before we try to ride them. We do run some horses, but we've got about 60 head and we run 45 mules right now, and the rest are geldings; don't have any mares.

So yesterday was the first time you had been to your outfitter camp since the wild fire came through here?

Yeah. We came in in 2011, I think it was, before the Mustang Fire. Much, much different trip. A lot of the early part of the ride was the same. In fact, right now we're just getting into the edge of the Mustang Fire. There was a Saddle Fire that came through after we had ridden out. In fact, we were up here at the camp when the lightning storm came through that started the Saddle Fire. So we saw the wisps, and then it burnt, you know, some of that coming in, but yeah, the camp's much different. You know, it was all green, significantly more water flowing. This is a very dry year. We're in the late part of June, and it was dusty at 9,000 feet, so it's going to be a dry one and a hot one.

Sounds like fire is something you have to deal with on a regular basis here.

We've had probably six significant fires in the last seven years that has impacted the outfits quite a bit. I do believe fire's natural, a part of the ecosystem. And we were allowed to operate during some of the major fires, so we could get in and out and have a lot more close up and personal experience with fire than I really wanted to get into.

One of the reasons we haven't come up here is, since the fire, most of the public really wouldn't want to ride this far. We're going to go to a beautiful lake today. It wasn't burnt at all, so it's still very, very pretty. But, yeah, it does impact what a lot of the clients think about the wilderness.

And we talked a little bit earlier about European guests, you know, and they just don't get this at all. And you know, we tried for significant years to not have fire, and that didn't work very well for us. So we do have to have wildfire back here. The European countries just don't get it.

Not too far from your outfitter camp is a little spring.

This creek behind us here, it goes up to some rocks right there. And looking on the map, I do believe this is the official headwater of the Selway River. It is the start of Hidden Creek. And it goes down to Hidden Lake that we'll visit later. But this is the farthest year-round flow of water from the mouth of the Selway, so I think we're here.

It's a wonderful spring, very, very cold water. It comes right out of the rocks. Very, very little ground above it, and right now it's charcoal-filtered, so it's really good!

So tell us how you came to own an outfitting business.

I grew up in the Midwest, and my parents were teachers, so we did a lot of camping. So when I graduated from college I took a job in Boise and moved there, and just loved Idaho, loved the country. I enjoyed the four seasons. For me there was kayaking, fishing, hunting, and skiing, and I went all over the state. You know, I've done not all, but many of the rivers in Idaho, been in a lot of national forests and wilderness areas.

And you catch the Selway fever. It's just, for me, the most spectacular piece of Idaho. And I just love it here. So 15 years ago we moved to the West Fork, near Darby, Montana, to be near the Selway, and started an outfitting business up here.

There's some of the cowboy songs, wishing you were born 100 years ago. We don't need to be. When you go down these trails and the trail we rode yesterday, it looked like that 100 years ago. I can ride the lower Nez Perce Indian trail, same trail that Chief Joseph rode. The main difference, though, I think today is a result of some of the fires.

If you look, historically, they didn't have the same re-burn rates and the amount of fire. Chief Joseph wouldn't have made it to the Big Hole, you know. And I think Lloyd Magruder wouldn't have been able to get to Bannack if it was these conditions.

I think fire is a natural part of the wilderness. But two major effects, I believe, are the policy where we put fires out for several years, starting after the 1910 burn. So the amount of bio-mass that's in the forest, especially several years ago, it built up to unnatural levels, and then, you know, the climate change. So you have pretty much about 50-plus years of put every fire out during one of the wettest and coolest periods in our country's history; and now we're in one of the driest, hottest periods, and we let it burn.

We do need fire; I don't mean that at all. But we do, I think, since the conditions here are, not totally, but to some effect, at least exacerbated by man, that we can have a little bit more proactive and a little bit more judgment on what we attack, especially on those very, very dry years.

It's led to some really bad trail conditions. The way we came in yesterday was on a ridgetop so we could wiggle through a lot. And if you come up from the bottoms of these trails, it takes several weeks to cut them out, so, you know, it impacts trying to get around. As a result, we don't get a lot of use here. I don't think anybody used this camp at all last year.

I think folks would be amazed at just how rugged this country is back here.

The Selway's not for sissies. There's a very small percentage of the population in the US today that have the skills to come in on their own; it's probably in the 3 to 5 percent that have the equipment, that can afford the equipment, the stock, and have the skillset. So it is very rugged. We're also losing a big piece of the population that, even without the equipment, is in shape enough to come in, and just has enough skills to horse-ride and that want to do this.

One of the things that we talked about is what's the wilderness going to be, what's this going to be in 50 years? And are we losing the values of wilderness to younger generations? So we do a lot to promote that. I think the Fish and Game Department and a lot of other people are trying to work with young people to get them involved, to get them to put their video games down and get a tackle box and come to the wilderness.

That's one of the things that we try to do. We love sharing this, my wife and I and the boys -- just love sharing it with people. And the life-changing experiences that we get on trips, that's what it's for.

It's just an incredible place. And when you get out here and look around, there's nothing like this in the world, well, outside of Alaska. Yeah, it's a beautiful place, for the most part, and kind of hard to get around.

Dave Campbell is a retired district ranger with the U.S. Forest Service. He worked in the West Fork district for 17 years and made a lot of the calls on wildfires in the wilderness. Campbell joined outfitter Steve Burson for the trek into the headwaters of the Selway River. This interview was conducted by Bruce Reichert in the Frank Church wilderness in the summer of 2015.

Maybe explain just where we’re at for this interview.

We're at the headwaters of the Selway River, here just above Hidden Lake. The Selway flows north here for about 28 miles till it hits the Magruder Corridor, so this is one of the least-visited parts of the Frank Church Wilderness, because it's pretty hard to get here, as we witnessed yesterday. It’s not an easy horseback ride for an experienced horseman, and just behind us is the break that goes down to the hydrologic divide between us and the Salmon River, still in the Frank Church Wilderness.

I think the things that keep this from being more visited is it's just very rugged country, and not a lot of water on the Divide Trail, so you've got to be prepared for that. And the sheer distances make horse travel necessary. But, then, again, there's not a lot of feed, so then you have to carry feed with you. So it does tend to make it a little less of a popular place to go, I guess.

What role does fire play in this wilderness?

The Selway is really where wilderness fire started in the Forest Service. It was probably the vision of Bud Moore; you can't go very far without talking about Bud. And from 1972 with the very small Bad Luck Fire, there's been continuous wilderness fire management here, when possible, to allow fires to burn. So I always like to say that the default in wilderness is to allow the fire to burn because it's a natural part of the system. That's what created the forest we enjoy now. And it's a part of the Wilderness Act.

One of the ways in which wilderness is most trammeled across the country is by fire suppression and changing the course of natural events, which, if you read the Wilderness Act, doesn't make a lot of sense. As Bud said, if you read the Wilderness Act, it's practically illegal to put a fire out in the wilderness! So in the Selway we have this wilderness that is so large that we can actually, comfortably allow fires to burn. And since 1972 that's been increasing.

During my years at West Fork we routinely would have 15 to 20 fires in a normal year that were allowed to burn in the Selway, and then in the Frank Church, together, because the two wildernesses join each other on the West Fork District.

And over time, the systems become more or less self-regulating, because old fires check the growth of new fires. Old fires as they start to regenerate have younger timber that's not ready -- younger trees that aren't ready to burn will modify the behavior of the current fire, and they range anywhere from a single tree that just smolders and goes out, to the fire we're close to here, the Sweet Fire, about 30,000 acres at one point. The Gold Pan Fire of a couple of years ago was about 40,000 acres.

And in that 40,000 acres there is a lot of variability in terms of the way the fire touched the landscape, which is all natural. If the fire reaches particularly receptive fuels at a particularly hot day, you're going to have a pretty intense fire; whereas, if it reaches it in the evening and burns through there, you might have a nice under-burn.

You’ve dealt with fire most of your working life.

I was very fortunate to spend 17 years here at the West Fork. And because of that, I had a lot of opportunity -- I would phrase it that way -- to choose to manage fire in a natural wilderness way that protects wilderness character.

Having the opportunity to work at the district ranger level, particularly here in this ecosystem, for 17 years gave me lots of chances to make decisions on fires. In the wilderness the default should be to allow the fire to burn. And the successful wilderness fire is one that starts and ends naturally, without us trammeling for suppression or management. And there may be some differences in that. A lot of times we would protect the trail system, protect the bridges, that kind of thing, and allow the fire to burn.

And because of that relatively long tenure here, I've got to do a lot of that. Somebody asked me when I retired, how many fires? And I had to go back and count. And it was either somewhere between 280 or 300, somewhere around there. Different decisions. But some of those were, like I said, very small, and some were much more memorable. The Gold Pan Fire of two years ago was one that, I think, was very memorable. It crossed the Selway River in a big way.

We’re very close to the headwaters of the Selway here. What does wildfire do to headwaters?

Yeah, we're about as close to the headwaters of the Selway as you can get. I think about 50 yards behind us, is the hydrologic divide. The Selway is the crown jewel, really, of wild rivers in the Lower 48. It's one of the most difficult rivers if you're rafting. It's also one of the most wild rivers because there's only one launch a day. And it's an ecosystem that has all of the components, including wolves, including fire. As I like to say, the Selway is big enough, and the Frank Church is big enough, that their systems are big enough for wildfire and wolves to roam unhindered. And that adds to the whole experience.

And it's pristine. At the headwaters here we dipped right into where it comes bubbling out of the ground, and it's pretty darn pure. And the Selway is a very natural system. There's no changes to the watercourse all the way along it. And fire, like I said, is a part of that. So, at times, when we have a fire anywhere in the Selway, and that's followed by a rainstorm, sometimes the Selway would be very dark-colored, but naturally dark-colored. And that's a system that all the aquatic species, in this case, Chinook salmon and steelhead, adapted to. And recently, some of the research done has shown that those kinds of large disturbances actually aid fish by producing the right kind of spawning gravels for reds.

I imagine you can’t help but sympathize with those who are trying to make a living here in this wilderness, with all the wild fires.

The wilderness is not meant to be convenient or easy. But in the Wilderness Act it does say “those necessary for the enjoyment of the wilderness.” So outfitters and guides are critical to that, because many people don't have the capacity or the ability or the time to acquire the skills to pack a horse or to do something like that.

So when we talk about the future and the current fans of wilderness, they have to have a chance to see it. And so we look at the outfitters as a partnership and hope that they will convey the wilderness story and have a passion. And that's pretty true or they wouldn't be here for the wilderness setting. And so, oftentimes, they end up telling the Forest Service line: Why is this fire here? Where is that son of a gun that allowed this fire to burn? Can I go ring his neck?

And they [outfitters] might explain that fire is a part of the ecosystem and that, especially in the Western United States, the forests that we enjoy now are born of fire. And in wilderness, in particular, one can't have a short-sighted attitude because really we're managing it for into perpetuity.

Will our grandchildren look back and say we did a good job? And in the meantime, we're standing here in a bunch of black timber; but there's young trees growing up underneath it, and that's how they got started.

Where are you in the whole climate-change debate?

I'm not afraid to use the word "climate change," for sure, because we're seeing fire seasons longer. They start earlier, last longer. There's more high-intensity days during a fire season. Fire sizes are larger. But, interestingly, in the wilderness where we've had active fire for a number of years, we're probably better prepared for climate change than outside of wilderness where we're been suppressing fires for so long.

I use the analogy, when talking about managing fuels to people, I say, "If you could imagine your wood stove, and you decide to put a stick of wood in it every day, but don't light it for six months, and then you light it, you have a different fire than if you'd lit it every week and then put another stick of fire." Because the biomass is always accumulating.

So what Mother Nature has done here is manage the fuels to a natural setting, so now when the fire strikes, when the lightning strikes, and it hits receptive fuels, it's not going to find as much fuel in some places, or it's going to be modified by past fires. So, really, in the climate change arena I think it's a good model for the essential role of fire in the system.

We've been drinking the wonderful headwaters of the Selway. Do you think our grandchildren will be able to taste water like this?

Yeah, I think so. I think they'll be able to enjoy the area just like we do. And the Wilderness Act mentioned, "for this and future generations." And what we do now in the wilderness with good stewardship is how that will be there for our children and our grandchildren, you know. And that's who we really need to think of.

And a lot of these black trees will be on the ground by then. There will be new forest growing up underneath it. The spring will be there. They can still drink that beautiful, clear Selway water and think about how far the Selway has to go to the ocean and how many Chinook salmon and steelhead are coming upstream and how fires and wolves, and maybe, by that time, grizzly bears are roaming through the Selway.

Wallace Ulrich is the former director of the Wyoming State Geological Survey and former Wyoming State Geologist. This interview was conducted by John Crancer in Jackson Hole, Wyoming in July of 2015.

Let start with a question about the general geology of the Continental Divide that forms the backdrop for the upper Snake River watershed.

One of the world's largest volcanoes, probably the largest one, we think…the Yellowstone volcano. And its activity over the last, probably, 20 million years, has really defined the general ecology and geology there, but also what was called the "Laramie Disturbances," a huge movement of the continent coming over top of the western area, which uplifted everything after the Cretaceous Seaway. So those three tend to define what we think of as sort of the general geology.

What factors contribute to all the water flowing off the Continental Divide in this area?

Well, probably two things: We have the elevation of it in Yellowstone, which, of course, as you know, is glaciated, and there are still remnants of glaciers there. The snow trapped in the winter there is enormous. We have a lot of rains in the summer depending on it.

And so the geology, the subsurface geology, too, enables water to percolate into certain areas and migrate off of that. The hydrology is very interesting. And you have such a large drainage area that's unencumbered. And that moves on down in these vast interconnected network of streamways, both to the Pacific and to the Atlantic side.

What role have volcanics and glaciers played in sculpting this upper Snake River area?

The concept of the continent moving over the top of hotspots, that science now sees and has defined a little better, they stretch all the way to the West Coast. So if you look on an aerial, you can see this wake that's been 60 million years in the making of many, many ancient Yellowstones. And as that continent has moved over this, it creates much like a bulldozer, pushing. You get lots of gigantic pushing and shoving and breaking. And the explosions from Yellowstone and these massive volcanics that take place, long, thousand-year flows of lava, have created all sorts of opportunities for topography changes and the subsurface.

One of those has been the very rapid rise, probably within the last 5 million years, of the Grand Teton Fault, which has gone up about 17,000 feet and down almost equally. That's an enormous amount of displacement in a few million years. And they have no foothills, so you can see right into them and see the glaciers that are still there.

You also have the vast drainage south of Yellowstone in a very complex geology. Again, somewhat based on this massive volcano that's there, but also this enormous uplift that took place, that's called the "Laramie Disturbance," following the Cretaceous Seaway 100 million years ago that migrated away as the continent lifted up.

And the glaciers that were here, that were a couple of miles above Yellowstone and filled this valley, with just a little bit of the Tetons sticking out, of course, sculpted the valley. And when we have glaciation again, it will change it so you won't recognize the valley. Glaciers are quite efficient at that.

Does the current Snake River route follow the path of the old glaciers?

Yeah. As it comes out of the Yellowstone area, it comes down and goes into a sort of the northern, like a horse tail of the Teton Fault. There's numerous faults that spread off there around Flagg Ranch. And then it goes into the Jackson Lake, which, itself, has altered over time.

The outlet used to be right along the mountains. And if you look at a map, you can see that outlet has changed to where now it's facing to the east where the present dam is. Because there is subsidence to the east of the park -- or in the park, actually -- where the Snake River then takes a southern turn where it comes in, and that area is subsiding.

So that, then, allows it to go on down the Teton Valley based on the glaciation and the big fault. And through numerous faults it has cut its way through the overthrust region, which is extremely active, still, the whole back fault and various faults through the canyon there, fault plains. And the overthrust, of course, is this region where beds have been flipped over top of each other, starting about 40 million years ago and continuing. We've got lots of activity still down there on some of the faults. And then it hits to the Palisades and follows the old route down from there. A lot of that is glaciation. And, of course, huge melts cause lots of it.

We also have gigantic landslides that have taken place, one at Bailey Creek area that filled the valley here for several thousand years in Jackson Hole. This is an extremely active area. Lots of little faults in areas and nothing on the big fault for a long time, but it will come.

Is it unusual to have the high Continental Divide so close to the high rise of the Tetons? Is that unusual, geologically, in this country?

Not really, no. The Yellowstone volcano is such a monster, and it's caused a great deal of this. It provided the opportunity for that fault, probably. A number of these massive volcanoes have similar trending faults to the south of them, I'm told. Many of them are studied for that. It's a fascination because they so seldom really explode. And there's lots of studies going on it now.

That energy can distort the subsurface rocks and cause movement. Things shift in one place or another. We didn't think this many years ago, but it's been proven now that even as far away as Alaska we've had events, large events take place there, the domino effect down various faults into the Rockies. And so the earth is constantly changing.

The Teton view, itself, just fascinates people. There isn't anything like it. And Yellowstone's -- the wildlife in Yellowstone -- the fact that it's such a big volcano, and you can't really see it as a volcano, traps people in that, immerses their imagination in these realms long gone. And they can feel like they're outside. Very few wander around. We have from 4 to 5 million, now, coming through here. And, yet, those of us who live here know that in five or ten minutes we can be on the trail where there is no one.

And that's much of the Snake River drainage. It's a fascinating part of our world. The watersheds have been well protected, I think. There are lots of things still to do with water protection. But I think we're a species that once we see we've messed up, we fix it. So habitat protection keeps us safe. Those of us who live here and have lived off of the land have a special way of knowing we have to take care of it. And the more people who come here, I think they'll learn, as well, that you have to pay attention to that.

How did the Headwaters Legacy Act happen?

First, most of these wonderful preservation events -- Yellowstone, Grand Teton, creation of Fossil Butte National Monument -- things like that started by either one or two people sitting down and saying, we've got to do something. We see opportunity, and we see a problem. The same happened there. And when you have someone that's willing to build a partnership and willing not to get credit, you can just do anything.

So the headwaters project, I thought, was large and involved not just a few people, but numbers of governmental agencies and different kinds of lands that are being used in Wyoming, and that makes it all difficult because the government doesn't move the same in state or federal or local. And yet all of these came together, people came together, and I think gave us something that is going to be lasting, and an awareness, the educational aspects of it.

What do you think the Snake River represents in western lore? How significant of a river is it?

The Doane Expedition put on some of their notes that the Indians called it the "Accursed Mad Dog River." And one of the local companies has used that name as theirs. It's a river that is just extremely powerful and a little mystifying because it has such a drop. So the velocity is enormous. Its carrying capacity is enormous, and it fools people. And it's very cold.

So that kind of wildness stopped much of the road building to come across it. It wasn't until 1937 that we had a road up the Snake River Canyon from the south. It's a very hard place to get to and stay in. We know that in a couple of weeks if the roads aren't continually maintained, you couldn't get in and out of this basin.

The Snake River, it's such a high-energy river. But it also provided an enormous amount of water that was trapped, in some places, 1900 here, that fed part of the nation; it continues to.

So it's a river that starts out in some of the most pristine part of the continent, right on the divide, and moves itself to the great Columbia through some enormous geological changes, most of which, were in the path of the great Yellowstone volcano. And it has provided us with ways and means to live, but also it's such a beautiful river. And it cuts its way through such enormously gorgeous geology that you just salivate.

Ron Abramovich is a water supply specialist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service. He has been measuring snowpack levels in Idaho for more than 25 years. This interview was conducted by Bruce Reichert in November of 2015.

What is the relationship between snowpack and headwaters, particularly in the Salmon River country?