Pathways of Pioneers

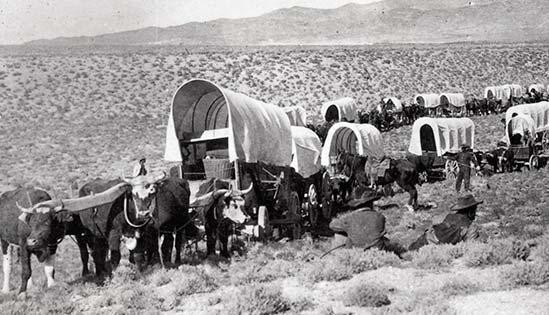

The great migration west along the Oregon and California Trails shaped the course of a nation and forever altered a way of life for Native Americans. For the emigrants, the Oregon country offered them a chance for free land and a better life. That chance would come at a cost, though, as nearly one in ten died along the way. Sacrifice and determination walked hand in hand with the pioneers striving to reach their westward goal.

The change set in motion by the great migration left a lasting legacy on Idaho and the rest of the country. Traces of the journey are now hidden amidst the intractable march of progress. Learn more about the trail and its twisting course through our state and the west as Outdoor Idaho follows the Pathways of Pioneers.

Landmarks

Not long after the emigrants crossed Thomas Fork Creek in what is now Idaho they faced one of the most challenging obstacles of their journey…Big Hill. A strenuous uphill climb was followed by one of the steepest descents along the entire Oregon Trail.

"We went a few miles further when we had to cross a very high hill, which is said to be the greatest impediment on the whole route from the United States to Fort Hall. The ascent is very long and tedious but the descent is still more abrupt and difficult." --Theodore Talbot, Sept. 7, 1843

"And the braking systems they had on those wagons weren’t the best. They were hand held and hand held metal on metal almost but you can’t let your wagon run into the back legs of your livestock. I just think they had to work with the hand that was dealt them. There you are in July, it’s hot, you’ve got this hill, and it’s going to be tough. We’re going to work together and we’re going to take a wagon at a time. It’s going to take us all day to move all the wagons over but that’s our day." --Ross Peterson, Historian

"Oh my, just the steepness of it alone. Here they are trying to hold back wagons down a grade that in a diary entry said was as steep as a slope of a calf’s face and sheer granite with not a lot of dirt… so they were trying to hold back an immense amount of weight there and then to know that every possession you ever owned, the only thing you owned in your whole world was on the back of that wagon coming down. It was a tremendous feat that they came down." --Becky Smith, National Oregon-California Trail Center at Montpelier, Idaho

The Clover Creek camp site on the Oregon Trail was located in the Bear Lake Valley where Montpelier, Idaho stands today. It was a welcome stopping place for the emigrants who had crossed the desert of western Wyoming and overcome the challenges of Big Hill.

"There were all these fresh, refreshing rejuvenating things waiting for them in this valley to be able to spur them on, because once you leave the Bear lake Valley you go back into that wilderness or that desert especially down by the Snake River and the Massacre Rocks area." --Becky Smith, National Oregon/California Trail Center at Montpelier

As director of the Oregon/California Trail Center, Becky Smith appreciates the facilities historic location on the Clover Creek encampment site. The center celebrates the heritage of the trail and also gives visitors a feel for the journey with their living history presentations. Through her various roles at the center Smith feels she’s continuing the legacy of the Oregon Trail.

"Well I do feel a connection with the pioneers who have travelled this way and especially when I work here at the Oregon Trail Center. It’s so important for us never to lose that zest for life that they had, that there is a chance that you can do something over or you can make it better and I think if I had one wish it would be to be able to every so often recreate that and have more facilities like this where people can come and touch base with the past, learn from the past so that we’d have a better future." --Becky Smith, National Oregon/California Trail Center at Montpelier

Continuing up the Bear Lake Valley from Clover Creek (Montpelier), Oregon Trail travelers soon reached the next important stopping place, Soda Springs. The area was well known by emigrants for its abundance of unusual springs.

"Travelled about 22 miles along the bank of the Bear River and are encamped at Soda Springs. This is indeed a curiosity. The water tastes like soda water, especially artificially prepared. The water is bubbling and foaming like boiling water." --Sarah White Smith, July 24, 1838

"You could hear Steamboat Springs which was the most renowned one as you came into the valley from the east they could hear rumbling and roaring. And there were just a huge number of carbonated springs, regular springs, cold water and just sulfur type smelling springs. The whole area was laced with them. And they camped and explored, probably spent a few days here. It was quite a phenomenon to them. And on a calm day you can go out on the back of the golf course, you can look over the reservoir and you’ll still see the rings as Steamboat continues to bubble." --Tony Varilone, local historian

Alexander Reservoir now covers both Steamboat Springs and sections of the Oregon Trail that pass through the area. But if they look closely, visitors can still see wagon ruts running through the nearby golf course and at Oregon Trail Park on the shores of the reservoir.

In the towns Fairview cemetery the wagon box grave provides another direct tie to the past. It contains the remains of a family of seven who were killed by Indians after staying behind the main party to look for lost horses.

"It’s called the wagon box grave because they dug a hole, put the wagon box – took the wheels off – put the wagon box in the bottom, covered them up with their blankets and buried them and marked the grave. And there were enough people still hanging around or who were hanging around in this area that it became known as the wagon box grave and permanently marked." --Tony Varilone, local historian

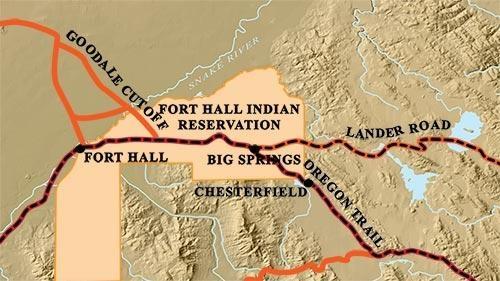

Fort Hall was one of the most important landmarks on the Oregon Trail. The British trading post was originally built by American Nathaniel Wyeth along the Snake River in 1834. Three years later, in 1837 it was purchased by a Britain’s Hudson Bay Company. They improved the structure by encasing the square log stockade with adobe brick.

"Paid a visit to Capt. Grant. Fort Hall is a small and rather ill constructed Fort, built of 'Dobies.' It was established in the summer of 1834 by Nathaniel Wyeth, a yankee. He could not compete with the H.B. [Hudson's Bay] Company and finally sold out to them. The Fort is near the entrance of Portneuf into Snake River. The river bottoms are wide and have some fertile lands, but much is injured by the slat deposits of the waters from the neighboring hills. Wheat, turnips have been grown here with success. Cattle thrive well." --Theodore Talbot, Sept. 14, 1843

Within a few years after the British purchased the post it became a major stopping place for thousands of Americans travelling west along the Oregon Trail.

"It was really the only place where they can have supplies, where they can meet other people and where they can take a break between Soda Springs and the rest of the most arduous part of the journey. It plays a significant role in the landmarks of the trail and so for trail travelers they are keeping track of where they are according to landmarks like South Pass and Fort Hall. The Hudson Bay Company though is a British trading firm. They really don’t care about American settlement and ultimately they will be forced to leave the region so, it is an ironic relationship there." --Laura Woodworth Nye, History Chair, Idaho State University

Fort Hall was shut down in 1855 after the Ward massacre which occurred in the Boise area much further west on the trail. But the escalated tensions between the emigrants and the Native Americans made commerce difficult. The U.S. military built a second Fort Hall years later northeast of Snake River. The original Fort Hall quickly fell into disrepair and little remains of it today. The site, marked with a simple marker is all that remains today. It is on the Shoshone-Bannock reservation and tribal permission is needed to visit the area. If you want to see what Fort Hall used to look like an excellent replica has been constructed south of the reservation in the city of Pocatello.

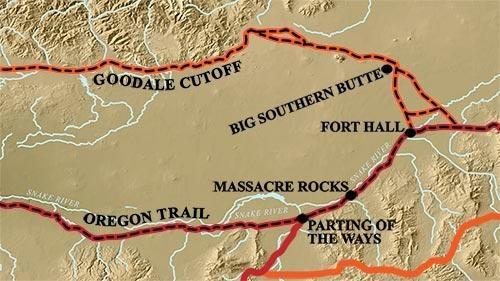

By the time the wagon trains reached what is now Massacre Rocks State Park, the emigrants had travelled over twelve-hundred miles from Missouri. Many considered their trek through the Idaho desert as one of the most difficult parts of the journey. Today, cars and trucks speed down today’s Interstate highway with few realizing how the pioneers struggled to cover the same ground.

"The Oregon Trail here essentially is in the middle of the interstate. The emigrants for the most part followed right where highway 30 was and then when the interstate went through the interstate just simply took out more of the Devil’s Gate. The Devil’s Gate or the Gate of Death is still there. It’s just slightly larger than it was during the Oregon Trail era. When the Oregon Trail was going that gap through the rock was only wide enough for one wagon to go through. Even though no attacks of emigrants happened there to the emigrant’s point of view Massacre Rocks—attack sketch [Courtesy Idaho State Historical Society, 60-150, Shaw]whenever they had to go through a very narrow gap of rocks or through trees or a canyon they were always concerned about being attacked. The actual Indian skirmishes that happened in 1862 happened further east of what people termed the Massacre Rocks even though that name never came about until much later." --Kevin Lynott, Ranger, Massacre Rocks State Park

The attacks that took place on August 9th and 10th of 1862 occurred along the trail east of the rocks. They claimed the lives of ten emigrants and involved a total of four different wagon trains.

"Mr. Hunter, who was captain of our little train gave orders to get ready their firearms and prepare for fight, and right speedily was the order obeyed, considering the surprise in which we were taken, together with the fact that not one of us had ever been called upon to defend our lives or property by the use of such weapons." --Charles Harrison, Aug. 11, 1862

Visitors who stop at the state park today can learn more about the attacks and also get a close up look at some well preserved ruts or swales.

"Here the more common term is swales. Ruts are what you consider of twin wagon wheels shown in rock. Here, because it’s highly erosive ground what you have is more of a ditch effect. Unless they had no option whatsoever to bypass rocks you very seldom see ruts per se. You see swales across Idaho for the most part." --Kevin Lynott, Ranger, Massacre Rocks State Park

A few miles west of the swales, the names carefully etched into Register Rock reach back to the days when this area was a prime camping spot on the Oregon Trail.

"Register Rock was one of the more popular camp sites in the area and that was principally because Rock Creek was emptying into the Snake River there so there was better feed and it just happens that the Bonneville Flood had rolled a huge boulder right in the middle of their camp ground and so early on the emigrants , where ever they could, left their mark. Sometimes it was just a pencil drawing on an oxen skull but where there was rock and where they had time they actually chiseled their names into the rocks and there are several hundred here. Some have been lost just through erosion through the years but you can still see quite a few names." --Kevin Lynott, Ranger, Massacre Rocks State Park

From the Massacre Rocks area the Oregon Trail continues west, generally following today’s interstate highway. When the emigrants reach the Raft River valley in the 19th century there was a broad river to cross. All that’s left of the river today is an irrigation ditch.

show text

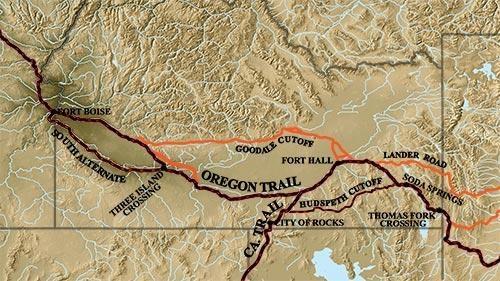

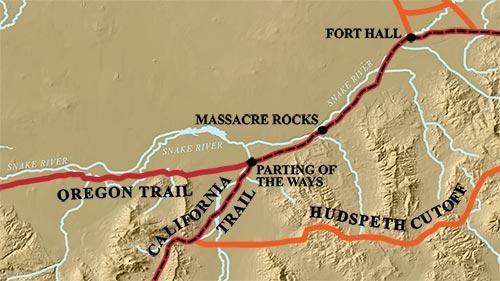

But on the plateau above the river valley is a major landmark of the trail…the Parting of the Ways. Here emigrants heading for the gold fields would turn towards California while those bound for Oregon would push on due west.

"At noon crossed Ford Creek & at night reached Raft River & encamped. Grass good. At this point the two trails diverge for California and Oregon. We met here quite a train taking the Oregon Trail, mostly families." --Henry Tappan, July 23, 1849

"Until 1849 the Oregon Trail is headed predominantly to the Willamette Valley and once the Gold Rush takes place in 1848, 1849 then the majority of travelers on the Oregon Trail will be headed to California and so it’s really a misnomer to say that it is the Oregon Trail because it becomes the California Trail once those travelers turn off, and they diverge just south of what is now Raft River Idaho and they head into Nevada and into the Sierras ultimately." --Laura Woodworth Nye, History Chair, Idaho State University

Just below the Parting of the Ways is the lonely grave of a woman who died from wounds suffered during the Indian attacks in the Massacre Rocks area.

"Mrs. Adams, who was wounded in the fight of the other train, died last night. We buried her this morning. Here some of our train will leave us and take the road to California." --Robert Scott, August 12, 1862

Emigrants heading southwest on the California Trail followed the Raft River for many miles. Later they would reach another landmark not far from the current Idaho/Nevada border . . . the City of Rocks. Today, the area is protected as the City of Rocks National Reserve.

The emigrants were impressed with the huge stones and boulders they found here. Some stopped long enough to record their passing by writing their names on the rocks with axle grease.

"This morning we started early, at half past five o'clock and nearly all day traveled over rough roads. During the forenoon we passed through a stone village composed of huge, isolated rocks of various and singular shapes, some resembling cottages, others stooples and domes. It is called 'City of Rocks' more suitable. It is a sublime, strange, and wonderful scene—one of nature's most interesting works." --Margaret A. Frink, July 17, 1850

Rock Creek was a prime camping spot and resting place along the Oregon Trail. In the mid 1860s a stage station and store were built near the creek.

"One of the journal entries called it an oasis in the desert. It was an important stopping place. They could stop here, they could get water, they could bathe, they could fish. It was important because of the creek." --Curtis Johnson, Friends of Stricker

Today, there’s not much left of the stage station although the 1865 store is still standing.

"You wouldn’t know by looking around now but it was the largest stage station between Fort Hall and Fort Boise so it was a very important stopping place. The stage station itself was a lava rock station with a sod roof and it could house up to forty horses and it also meant you could get a warm meal here in the evening time. And the store was built to provide supplies and it was located here because of the lava rock cellars behind it." --Curtis Johnson, Friends of Stricker

In 1876, Herman and Lucy Stricker bought the store and later built a home on the location. Curtis Johnson is their great grandson.

"To me this represents how history shifts and moves so easily. When Herman and Lucy were living here this was a major thorough way. This was like the freeway of the 1800’s and then the railroad came through on the other side of the canyon and it kind of shifted the whole migration of people to the other side of the canyon. To know where we came from helps us value where we are today." --Curtis Johnson, Friends of Stricker

The Stricker Store and Home are owned and managed by the Idaho State Historical Society with help from the Friends of Stricker. There is a new interpretive building at the site that provides additional information on the history of the area.

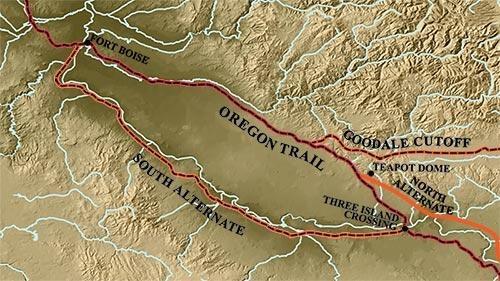

At Three Island Crossing emigrants on the Oregon Trail reached a critical junction. Here they had to decide whether to make the difficult crossing of the Snake River or take a longer alternative route along the south side of the river.

"Some of the hardest things the emigrants had to do were crossing rivers. When you read the diaries there are a lot if incidents of deaths at the river crossings. So when they get to Three Island Crossing they’ve got a decision to make. They could continue on down the south side of the Snake which was known as the dry and the longest route and the more desolate Wagons crossing riverroute or they could risk crossing. …. So it was whether you wanted to risk drowning or take the long route." --Larry Jones, Idaho State Historical Society, retired

Today, local residents in the Glenns Ferry area honor their pioneer heritage during the annual Three Island Crossing event. Every August, since 1985 they’ve reenacted the crossing at this historic spot.

The area is now an Idaho state park complete with a history and education center. Yet, actually witnessing a crossing leaves a vivid impression on the hundreds of spectators who line the river. Roy Allen has been part of the event for over twenty years and has participated in all but two of the reenactments. In his late seventies he’s the oldest man still crossing the river.

"It’s a little bit exhilarating when you know you’re coming into the swimming water, pretty quick you feel your old horse start swimming instead of walking, you hope he can swim good." --Roy Allen, long time Three Island Crossing participant

For many onlookers seeing this crossing is more real than any history book could ever be. And for the participants there’s great meaning in continuing this tradition.

"Both sets of Great Grandparents crossed this river, so it’s a way to honor them and remember them and when we make it across its such jubilation you know when you think about your heritage and how your ancestors must’ve felt and you thank God that you’ve made it and everybody’s safe." --Julie Blackwell—Three Island Crossing Participant

The point is named for U.S. Army Captain Benjamin Bonneville, an early Idaho explorer whose party reached this viewpoint along an old Indian trail in 1833. Later, it became a fondly remembered location for emigrants on the Oregon Trail as they took in their first view of the Boise River Valley.

"The real viewpoint for them is when they get on Bonneville Point. They hadn’t seen trees for many miles and when they are on Bonneville Point and they are looking over the beautiful Boise valley they see the greenness along the river, the trees and the grass they know they’re going to have good water and they are going to have good grass once they get down there. So that was a pretty joyous occasion for all of them when they get up there." --Larry Jones, Idaho State Historical Society, retired

"It was getting late when I reached the top of the Big Hill, around which the road leads to the Plain, which is spread out at its base, almost as far as the eye can reach; broken in the distance by the Mountains in the regions of the Malheur & Burnt Rivers. To the right rose up that majestic Range of mountains, which is the source of the river below, and from which we issued yesterday. Below, thousands of feet below, were seen the water of this beautiful river winding there tranquil course & gleaming like a thread of silver in the rays of the setting sun. The stream seemed as calm and gentle, as if its way was through a meadow, instead of rugged canyons. After reaching the plain, the course of the stream is marked by a line of green timber, which gave rise to Bonneville point—view from pointits name among the early trappers 'Boisse' or the 'Wooded River'. This green strip of vegetation winding its way through the desert sage plain, gave a more cheerful prospect to the view and after gazing once more on the vast map spread out before me I rapidly descended the hill to find a camp for the tired train; but never can the recollection of the grandeur of that scene be blotted from memory... . the sunset from the Big Hill of Boisse will always be a greene spot in the past." --Winfield Ebey, August, 1864

Today, Bonneville Point is a Bureau of Land Management site complete with interpretive signs and historical markers. And though it has changed significantly in the last century and a half, there’s still a great view from the point.

The city of Boise actually owes its beginnings to the United States Military’s Fort Boise. While the original Hudson Bay’s Fort Boise was a trading post built years earlier on the Snake River, the military fort was constructed near the Boise River in 1863.

"There was talk that we needed military help for the emigrants coming through. Nothing happened until after gold is discovered up in the Boise basin and then the movement really took hold and we have Fort Boise the military one founded on July 4th, 1863 to serve not only the miners and the new settlements starting to grow up but also the emigrants who were still coming through.

We still have some of the original buildings there from 1864 and 1865 and up to the turn of the century so it is a place where you can go over and see what a military encampment might have looked like – and Fort Boise was economically one of the boons for Boise city for many years. --Larry Jones, Idaho State Historical Society, retired

Fort Boise was originally constructed near the intersection of the Oregon Trail and the roads connecting the Silver City and Idaho City mining areas. Today, all around Boise you can find plaques marking the route of the Oregon Trail through the city.

Fort Boise was originally built by Thomas McKay of the British Hudson’s Bay Company in the fall of 1834 near the confluence of the Boise and Snake River. The post was a response to Fort Hall, the trading post built by American Nathaniel Wyeth a couple hundred miles upriver on the Snake near what is now Pocatello, Idaho. The Hudson’s Bay Company would soon own both forts but with the decline of the fur trade the posts served became primarily used as rest and resupply stops along the Oregon Trail for the thousands of American emigrants who were heading west.

"We reached Fort Boise. This is a trading post of the Hudson's Bay Company, established upon the northern side of Snake or Lewis River, and about one mile below the mouth of the Boise River. This fort was erected for the purpose of recruiting, or as an intermediate post, more than as a trading point. It is built of the same materials, and modeled after Fort Hall, but is of a smaller compass. Portions of the bottoms around it afford grazing; but in a general view, the surrounding country is barren... At this fort they have a quantity of flour in store, brought from Oregon City, for which they demanded twenty dollars per cut, in cash... At this place the road crosses the river, the ford is about four hundred yards below the fort, and strikes across to the head of an island, then bears to the left to the southern bank; the water is quite deep, but not rapid..." --Joel Palmer, September 2, 1845

Fort Boise was particularly susceptible to flooding and was actually moved several times in the generally vicinity of the confluence. Both Fort Boise and Fort Hall were shut down after the Ward massacre in 1854 escalated tensions between the emigrants and the Native Americans. Boise River floods destroyed all remnants of the fort by the 1860s and today all that left is a small historical marker.

The site is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is found inside the Fort Boise Wildlife Management Area. Though the fort is no longer there visitors can get good views of the Snake River from the river banks where the post used to stand.

In Parma, just up the road from the original fort site, there is a replica of Fort Boise and additional historical information.

Trail Historians

Idaho State Historical Society, retired

John Crancer – What is the Oregon Trail?

Larry – For everything to come together as with every movement there needs to be an atmosphere right for change and this was certainly the case in the late 1830’s and the early 1840’s. Malaria was running rampant in the Mississippi Valley, there was a depression and there had been lots of information available in the last few years for them about the Oregon Country.

The primary information coming out was this should be our land – not England’s. In 1818 we signed a joint occupation with England and Great Britain for occupation of the land. So the theory was if we got all the white settlers over there then we’d have a stronger case to make for the land. So with that intact and the settlers around there having some problems some of them decided to immigrate.

The big emigration starts in 1843 and there were nearly a thousand of them and prior to 1843 there had been a few who went to Oregon following the missionaries and looking for farm land but they had never been able to take their wagons past Fort Hall. They were always told that it was too rough. Marcus Whitman had gone back to the east to try and get more money and support for his mission and he met them near Fort Hall and he said we can take wagons. So they were the first ones to take wagons through and then once it was proven that wagons could go through then more people started to come. They didn’t come in droves at first. Prior to 1848 there were probably 15,000 who came and probably 4,000 or less who went to California but then what happened in 1848 was the discovery of gold and that gold fever pretty much swept the nation and then we start seeing more and more coming along the trails. Not all of them are going to California. Some of them still go to Oregon but the vast majority of them were going to California but they were still using trails that we have here in Idaho.

John – What were the prime years of the trail and how many travelers were there?

Larry – The prime years of the trail itself were probably 1841 to 1860 according to most historians and during that time, that is when we have pretty much a rough estimate of how many were going.

They say – depending on who you look at for estimates that 400,000 to 500,000 went to the west coast. The majority of those went to California and during that time period there were probably 100,000 who went to Oregon. The rest were going to California. Now that estimate is going to go up some because the Oregon/California Trails Associations have been researching the southern trails which have never been looked at before so that will probably add to the total during those years. But I have found after 1860 we still have more and more coming, using the trails because of gold discoveries, the opportunity for free land and cheap land and so we could probably add a few more thousand on to that.

The last good immigrant diary we’ve got is 1919 and we know there were people still taking wagons at that time. Even when the train came through and came to Kelton people were bringing their goods and buying wagons or shipping the wagons out after 1869 and coming, migrating into Oregon and Idaho at that time.

John – We’re talking about that there were still people on the trail until the early 20th century.

Larry – Right, until the development of the automobile and then even then in some remote areas we still have people still using their wagons. So the trails were in use probably into the ‘20’s and even probably the ‘30’s until there are more and more automobiles and then even then people tried to drive their autos, in the beginning on the trail and that didn’t work too good so they had to find new routes for the roads.

John – What kind of people attempted this journey? Who was travelling?

Larry – There is a whole spectrum of people who were travelling. In the beginning you mostly get farmers and some businessmen and entrepreneurs. You get what you might call today the wanderers or you might have called them hobos or whatever, they were drifters. And they really had no place to put their hat down in the Midwest and they were hooking on and trying to get a new start for themselves coming out. So you have a whole myriad of different types of people who were coming out here – but mostly its families looking for new opportunities

Now, it is always thought that these people were poor people when they were coming out here but that is another misconception because when you look at what it costs to come out here at that time with the wagon and outfit you are looking at four or five hundred dollars anyway and that was a lot of money back in the 1840’s. So these were fairly well to do people who were just moving on. And then you might get the occasional person who might move on because his nearest neighbor was within ten miles and he thought that was too close so he was going to move on farther west.

John – What were some of the biggest challenges along the trail?

Larry – Every day was really a challenge for them. They never knew what they were going to run into – in the beginning. Later on they had a good idea of what the challenges were before them but the real challenge for them was the camp grounds. They always had to have wood, water and feed for their animals. In the beginning, there was not too much problem finding these campgrounds but when you start – especially until they get over into Idaho – when you have like in 1852, you have 50-60,000 people going over the same trail, that is going to decimate the environment pretty good and that was also the time when they have all the cholera epidemics along the trail, when thousands die because of all the polluted water and all the waste along the way.

John – What were the essentials to make this trip?

Larry – Again, they always wanted to take grandfather’s clock along and there are a lot of grandfather’s clocks that ended out on the prairie. Some historians have called the trail just one large garbage bed.

The recommendation was that your wagon shouldn’t be overloaded. They thought the ideal weight was somewhere around 1,200 pounds. Some people would start off their wagons with over 2,000 pounds and that would include beds and stoves and all sorts of iron implements and those soon met the wayside. But you always wanted to have a good supply of food. They would have bacon and beans and rice and tea and coffee and sugar and flour. Those were some of your essentials that would get them out here.

In the beginning people thought that they could shoot wild animals along the way but that didn’t last for more than one or two years before the animals figured out they didn’t want to be anywhere near the trail and there just wasn’t much there for them. So they had to depend on some of the trading places that grew up along the trail from retired mountain men and so forth who would start trading spots along the way. Fort Laramie, Fort Bridger, Fort Hall and Fort Boise would be places – where if they had money – again, these people had to have some money with them to buy supplies and then they had ferries along the way that if they had the money they would get ferried over rather than try the dangerous crossings themselves. So it was a pretty expensive operation really, when you stop to think about it in terms of today’s money.

John – Why were there so many variations on the trail?

Larry – Again, it goes back to what we talked about – the essentials they needed for camping spots – the wood, water and the grass and as they would become decimated they looked for better ways. And once the gold fever strikes then you are looking for the fastest and the shortest way and so then you have new cut-offs that start up that they think are going to be faster when in reality most of them don’t turn out to be any faster. They are closer but they are harder and the time wise is pretty much about the same.

And then we get the government involved with the Lander Road which is our only government surveyed road for the emigrants in 1857 and again that was trying to make it a shorter and better travelled way for commerce to go back and forth. That didn’t really work either because it was shorter but again, on the Lander Road when you are going over a mountain range that is over 9,000 feet high you can imagine it takes you a while to get your team up and over that and down – although the grass and the water were better along that route and that route was later used along with Goodale’s Cut-Off for the cattle drives once we had a settlement out here and they are going back east to rail heads, they went these ways.

John – Did they do some improvements on the Lander Road?

Larry – Yeah. On a lot of the stretches they didn’t need to do it on but when they go directly west from south pass and over the mountain - Jim Bridger Forest and over in there - they had to do a lot of road construction and somewhat in Idaho too when we get over into the eastern Idaho section of it over by Kennikinet Canyon and over in there which is just west of the Fort Hall Reservation. It’s also called Terrace Canyon. You can still go over there today and see the rock work they did coming up through the canyon to get them up and over. And then when they get over into the Fort Hall area where they meet up with the main trail then there is not much road improvement until they get over into Nevada – today’s Nevada.

John – Give us a brief description of Goodale and why that was used.

Larry – Goodale was first discovered by the fur trappers and was later used as a route for some of them who were supplying the Hudson Bay post at Fort Hall. We know it’s also another shorter route and once you get through the Craters of the Moon it is pretty well watered and there’s lots of grass. We’ve got travelers going that way in 1852 and 1854 but it is a tough route until you get past Craters of the Moon so it didn’t really attract too many. But in 1862 when we were having all the problems with the native Americans west of Fort Hall a train of about a thousand met up with a retired or semi-retired mountain man, Tim Goodale and he took them on the Goodale Cut-Off and then it became a little more popular once we have all these people going that way. And it was also a route used – after settlement again, where they would take horse and cattle herds east of the trail heads in Wyoming.

John – What about the Hudspeth cut-off? What was the main motivation for that?

Larry – It’s the shortest route. But again, they forgot that they had to go over four mountain ranges. This was opened up in 1849. It takes off, instead of going northwest from over in the Soda Springs area, it went straight and they thought they were going to come out on the Humboldt. When they discovered that they didn’t come out on the Humboldt but they were still just about 80 miles south of Fort Hall one of them said that he was thunderstruck that they weren’t on the Humboldt already.

They also were somewhat dismayed to find out that the people they separated from who went up on the traditional California trail at that time through Fort Hall and then down Raft River, they met up at about the same time in City of Rocks. But it was shorter. If you were packing or on horseback or mule it probably would have saved you a little more time. But if you had wagons it wouldn’t have saved you hardly anything, but to them it was shorter.

John – Talk about Three Island Crossing and why that was such an important junction.

Larry – Some of the hardest things the emigrants had to do were crossing rivers. When you read the diaries there are a lot if incidents of deaths at the river crossings. So when they get to Three Island Crossing they’ve got a decision to make. They could continue on down the south side of the Snake which was known as the dry and the longest route and the more desolate route or they could risk crossing. Those who crossed would find better feed and wood and water but they would also have to cross the Boise again and then they would have to cross the Snake River again. And both of the routes came together just west of Fort Boise. After they crossed the Snake River at Fort Boise they would rejoin together. So it was whether you wanted to risk drowning or take the long route. And it would all depend on the time of the year they were there and what the water looked like – because we know today even from the crossings they have there, there are holes out there and that is what a lot of them found when they were going across.

The early travelers would meet in an Indian encampment there and the Indians were most helpful for a small pittance to help the emigrants get across and everything was fine. When we have problems with the Indians later on you had to pretty much make that choice on your own and some of them even thought that well, this is such a thing, once we got our wagons all caulked up let’s just float on down to the mouth of the Columbia or down to Portland. Well, as you might imagine that didn’t work either. Some of them tried that and one of them – the people who went by oxen train met the people, they were there before the people came down the river in their wagon. And some of them who started on their wagons we don’t know what happened to them.

John – How did they use the islands on the crossings?

Larry – They usually just used two of the three islands. If the water was right, the one island, the big island, the farthest one I guess to the southwest they would drive their cattle or horses on out there to feed but they would head upstream to get the right channel to get across. So they would usually mostly only use two of the islands.

John – How did the Snake River crossing compare to Three Island versus the one near Boise?

Larry – The one at Fort Boise would probably be just a little bit harder because they didn’t have the islands as sort of a stepping stone to get across and the one at Fort Boise usually could run a little swifter and could be a little deeper. They had some islands out there but they didn’t use those so it could be a little more dangerous. But again some of our retired fur trappers and the Indians at Fort Boise got together canoes and makeshift rafts and again, would charge them to go over. But it was a little more difficult crossing than Three Island.

John – What percentage folks went on the main trail versus the south alternate?

Larry – From my research and looking at the diaries I always thought it would be more that crossed because of the better camping sites but it is probably pretty much close to 50-50. It’s pretty close.

John – Describe the south alternate route. Give us a little more detail.

Larry – They encountered more of the desert aspects of what they’d come through. There would be a lot more alkyl idée dust and prickly pears and sage brush and there was some water but the grass – it’s a little dryer there and when they go on the north side they are right along the foothills so they are going to get the last good water and the last good grass where out there on the plains, more or less along the desert floor, they are going to be more in a desert environment and the chances for good grass and water are not quite as good as they are on the other side. But they would have some good geographic features to see. They would see Wild Horse Butte and they would be really close to the Owyhees. They would have some good views.

John – What would they see along the main route there?

Larry – They would get a few more creeks to pass which was good for the water and once they get over past Canyon Creek and up through that way they’d get into some granite again and again, that is where we’ll have some signature rocks where they can put their names upon the rocks and let people know that they were there or else let the relatives coming behind or whatever know they were on the right path and this was the way that they were going.

The real viewpoint for them is when they get on Bonneville Point. They hadn’t seen trees for many miles and when they are on Bonneville Point and they are looking over the beautiful Boise valley they see the greenness along the river, the trees and the grass and the smoke fires – the early ones of the native Americans and they know they’re going to have good water and they are going to have good grass and a chance to get fish to supplement their diet once they get down there. So that was a pretty joyous occasion for all of them when they get up there.

John – Just a little more on Canyon Creek and what kind of camp spot that was.

Larry – It was a good camping spot. They’d come through over by Teapot Dome Hot springs which is just north of Mountain Home. They had had a chance to rest and recuperate and wash their clothes and then they would hit another good creek at Rattlesnake Creek. But then at Canyon Creek they actually had a chance if they had time to maybe catch a fish or two to get through there and it is kind of a little green oasis. Of course when you’ve got a lot of people coming through the good grass along there is not going to last too long. But what happened as settlement goes and we have the development of stage lines we have a nice stage station put in there – Rock Stage Station which we can still remnants of today, and people always enjoyed there because they could always depend from the Daniels Family who built it and maintained it a nice trout dinner. So they all looked forward on the stages coming through there. Not so much in immigrant days because they didn’t have time to get a fish and pull out or dynamite to dynamite the fish or whatever they might have done.

John – More on Signature Rock and what you’ve seen there?

Larry – Over on Ditto Creek we do have a signature rock the people have left their names on right along the trail and again, you wonder why they leave their names on it and a lot of them when you read their diaries you will run across once in a while, or somebody says we left our names for one of the relatives or friends who are coming behind so they could have the idea that they were on the right track. And some of them they were taken by the history of it saying well, we’re here. Let‘s make this known that we were here and you can still see some of the names today.

John – Give us a brief overview of the different versions of Fort Boise.

Larry – It was recognized early on near the mouth of the Boise River that this was a place that the Native Americans like to come and have their festivals. From different states all around the Indians would gather there so when the overland historians came in 1811 they made note of this and they sent back John Reed to develop a small post there in 1813. Well, in 1814 the Indians didn’t care for him there and they soon wiped him out and so there was not much thought given to it until a few years later when Donald McKenzie who came out with the overland historians and then went back to Canada, he came back as a north westerner, with the Northwest Fur Company and he thought it would be a good place to meet and trade with the Indians but the Indians weren’t quite ready for him either at that time.

So nothing happened until 1834 when Nathaniel Wyeth came out and he had a lot of goods and he was going to supply the rendezvous over on Green River. Well, the rocky mountain people said they didn’t meet him anymore because Sublet came through with his supplies. So Wyeth headed on west and when he got over into the Fort Hall area he saw that this was a place where the Native Americans like to come so he built Fort Hall as a trading spot and then he went on west. Thomas McKee of the Hudson Bay Company was aware of this and he immediately talked the people at Hudson Bay Company into letting him start a Fort Boise as the Fort there that we know today even though it did move its location a couple of times as a supply point. And it lasted a little longer than the one at Fort Hall because going back just a little bit – when we had the 1818 joint occupation, by 1846 the U.S. had taken possession of the Oregon Territory. So in effect the Hudson Bay Company was on American soil and they lasted until about 1855 and they weathered some of the floods that came through but what they couldn’t weather was after the Ward Massacre and the problems with the Native Americans and then the Hudson Bay Company abandoned Fort Boise.

John – What were the prime years of the original Fort Boise?

Larry – 1834 to about 1855 were the prime years.

John – Talk about how it was used by the emigrants.

Larry – They looked forward to being at Fort Boise because Francois Payette treated all the emigrants quite well and he didn’t highjack them too much on the prices. And he also had a little small vegetable garden where the emigrants could get some vegetables if he had some left. So they all looked forward to going to Fort Boise.

And also when they got there some of his voyagers were also helping to run the ferry to get across there.

John – So it was a major landmark?

Larry – It was a major landmark and then even after we have the gold discovered and ferries developed there was a river site ferry put in there in 1863 that ran for a number of years until we have bridges put up. And that is also the place where the steamer Shoshone was built to supply the gold mines. Of course that didn’t work much because you need wood to run steam and when you are going up and down the snake river there is not much wood around. So the steamboat Shoshone didn’t last too long and it made a wild ride down Hells Canyon and eventually ended up over around Portland.

John – Talk about the second military Fort Boise.

Larry – The military Fort Boise, there was movement to get that fort build early even after the Ward Massacre. There was talk that we needed military help for the emigrants coming through. Nothing happened until after gold is discovered up in the Boise basin and then the movement really took hold and we have Fort Boise the military one founded on July 4th, 1863 to serve not only the miners and the new settlements starting to grow up but also the emigrants who were still coming through.

And the military played a big role in the development of southern Idaho because they would send out troops to help protect the trail and then we still had some Indian difficulties in the 1860’s and not until after 1879 did all this stop.

John – What can you see in the Boise area today with the original fort and some of the other areas?

Larry – Fort Boise, we still have some of the original buildings there from 1864 and 1865 and up to the turn of the century so it is a place where you can go over and see what a military encampment might have looked like – and Fort Boise was economically one of the boons for Boise city for many years until it was abandoned in 1913.

We can also see nearby here Bonneville Point where there is a small interpretive site up there that the BLM maintains and we also have the Oregon Trail historic preserve when sub-divisions were being built out there a number of agencies got together and thought we needed to preserve some of this and so it is a wonderful place where people can go out. There are three overlooks and a number of interpretations along there and that’s the actual remnants of the trail.

We also have just further west of here over near Middleton is the site of the Ward Massacre and there is some new interpretation there. It’s a nice little park where you can go and read about what happened there.

And then Canyon Hill where we are still working. Hopefully we are going to get something done to preserve that and get some interpretation over there to where you will be able to see where they come down off the hill and cross the Boise River and then there is a replica of Fort Boise over in Parma and then the Fort Boise site itself so there is still quite a bit to see through here.

John – Give us more information on what you are seeing at the Oregon Trail historic park.

Larry – Over by the Oregon Trail historic preserve I think there are three or four cuts there. There is one real early one which we are in the process of getting a kiosk built there and some interpretation where you can go and see where the early wagons came down and there is just room enough down through the lava for a wagon to get down. Then just west of there is another ramp that was built in the 1860’s to accommodate heavier freight and stage wagons and that was built up and it is quite an engineering feat to see what they did there. And that is still visible. Then a little farther west of that there is another cut that comes down and goes over hits Amity Road.

The number one thing that they want to do is get down there quick and get to the water and they also wanted to get down quick and get over to the ferry which was right down below there which took people on up into the gold hills up above Boise basin. So there are a number of things to view out there.

John – I wanted to talk about the OCTA convention and what was the significance or what was it like to have a national OCTA convention in Idaho.

Larry – The Oregon/California Trails Association always tries to have their conventions along trail sites. Number one, it’s a chance to renew old acquaintances and it’s a chance for the local people to become more acquainted with the historic features surrounding their towns and it’s also an economic boon for the local towns because we usually have four to six hundred people who come out here from all over the united states and all over the world in fact to attend these. So it is something that is looked forward to by a lot of local communities getting the trails association there. And again, all these people who come – some of them have not come to the area and they all want to go out and see the different aspects of the trails and different sections and it’s an opportunity for them to get out and do this. And it’s also a time to share information.

John – Talk about putting together the tours and how that is enthusiastically received.

Larry – Everybody was very enthusiastic this year about their visit here and we’ve heard nothing but kind words from people who were attending and also from the people who helped put it on. Everybody was most helpful and the people who came had nothing but [good] to say about friendly Idaho and how well they were treated here.

John – What did they think about the historic nature? Idaho has a lot of historic spots.

Larry – Idaho is fortunate and it’s kind of a double edged sword because all of our sites are pretty easy to get to so it is a chance to over-love a site more or less where in other states you are going to have to 4-wheel drive to get to these. Most of Idaho’s sites you can drive to in a regular car and then park and hike if you want to. You can’t drive on the trail but you can get to the sites. So they were most impressed with the accessibility of the historic sites in Idaho and how easily they could get to and view these sites. It’s amazing, some of these people have had ancestors who came out here and they just like to stand in the trail ruts and envision what happened years ago. I’ve seen more than one person with tears in their eye when they know that just minutes from here they can go stand in the ruts and they know that their relatives came through here.

John – What is the importance of the Oregon Trail Association and the Idaho chapter?

Larry – The national organization of OCTA and the Idaho chapter, they work hand in hand together and they are trying to preserve what we do have left because it is rapidly disappearing – more so in other states than in Idaho but we do have a number of problems and the Idaho chapter has worked in concert with the BLM to mark all the trails that still have remnants and also the local chapter works with private land owners who are generally most appreciative about letting people mark it as long as we mark it as private property and permission required before hiking across it.

So they work closely together and rely on the national for monetary support once in a while for preservation projects. But it has been a good working relationship and it helps to be in the local working with agencies like the BLM, like the National Forest Service and helping them to carry out their duty of preserving the trails.

John – What is the significance of the Oregon Trail to Idaho’s history?

Larry – I’ve thought about this some in the past and it is the same thing as why is history important to anybody. This is our cultural resource, it is non-renewable and it sort of defines who we are because when those wagons started coming, - I like to call them they are the wheels of change and we’re always talking about change and we’re still talking about change today. When those wagon wheels started rolling across Idaho the whole panorama of the west started to change and it is still changing today. And when you think about all these people who came out here and you read the diaries and the difficulties they had and the number of deaths along the way – we have monuments certainly for them in towns and museums but the real monument to them is the trails themselves. There are all these unmarked graves out there, the people who died and early on they would bury them in the trail because they didn’t want animals, or they thought the native Americans would come rip the graves up which was not true – they wouldn’t do that – but we’ve got all these, you could almost say it is one long graveyard for over 2,000 miles of all these people who gave their lives to settle this country. And I think we owe them a great debt of gratitude for that and appreciation and I always feel a sense of compassion for all these people who lost loved ones along the way. You can’t help but bring a tear to your eye when you read about a loving mother who lost her baby or her son or daughter and had to bury them along the trail and no psychologist along to help them out and see them through the troubles. They just had to get back on the wagon or walk behind and look back at a trail of dust and wipe the tears and move on further west. So I think it is quite a monument to who we are today.

John – How much is left of the trail and how much have we lost?

Larry – There has been a lot of change naturally. We still have 180, 190 miles of actual remnants of trails – all the trails, not just the main trail that we’ve marked through the years – but there are still more and more threats coming to the trail and the biggest trail now is the wind turbine. If you are walking out there to experience a trail you don’t want to walk under a wind turbine. But again, circumstances – how do you meet this? How do you settle on what is good and what is bad? And where can you put these? You can hide cell towers to some extent but it is kind of hard to hide a 400 foot wind turbine.

So there are still problems on the horizon that we need to deal with. Plus, with the increasing population there are more and more people who want to bring more power lines in and for some reasons – I guess it was probably because the trail took the shortest route – we have a lot of electrical lines going along the trail and it is kind of hard to keep those out of view but there are still a number of spots where you can really experience the trail.

John – What does the trail mean to people today?

Larry – There are a lot of people who don’t even know that the trail is around here so it is kind of hard to talk about what they think about it. When they find out about it they are amazed, which always interests me because all the newcomers – all the old timers around here they know about the trail but all the newcomers which we’re talking thousands, they are not aware of the trail so one of the things that OCTA tries to do is help these people become aware of what is out there. And most of them are pretty appreciative of the trail and are willing to do what they can to help preserve this because I think once they know the story and what it means to Idahoans and to the nation, then they themselves become more appreciative.

And I think we do a good job in the schools around here of educating the kids about it and the kids generally know more about it than their parents do. It is always harder and OCTA works really hard to get the kids involved in the trail. That’s how for future generations, if we’re going to preserve anything whether it be the trail or whatever, the school children need to get interested early on and I think that carries over with them.

John – What are some reasons people should care about the trail in the 21st Century?

Larry – I think it is even more today than in the past that we really need to appreciate our history even on a national level and an international level. If we appreciate our history I think it would help us approach solutions a little bit differently and not jump to conclusions so fast. And if we can look at the past we can use it as sort of a ruler as to how we might better deal with the present and the future. So I think it’s important for not only the trail but all our historic sites and history because once it is gone, it is gone. There is no way to replicate an eight foot rut of an Oregon Trail that has been windblown and there is no way on a ___ shed. Once you put a subdivision there it is hard to imagine what the emigrants went through when they came through here and it’s just a little bit harder to appreciate your history.

John – What kind of treasury is the Oregon Trail for Idaho? Is it a valuable resource?

Larry - The trail itself is a valuable resource for Idaho, not only for its historical purposes but also for the cultural tourism aspect of it. Cultural tourism is big these days. Maybe not so big now with the price of gas but if gas comes down we’ll see more and more tourists coming. And they all like to go see sites of the west or the wild west or whatever and this is especially true of visitors from overseas which has always been somewhat amazing to me as all the members in OCTA that are from Great Britain, Japan and all over the world are interested in this aspect of our history. And we have that aspect of our history out there. And like I said earlier it is also, we respect our dead with cemeteries and memorials but we forget about all the dead who are buried along the trails out there and we don’t know where they are. We know they are out there because we can read the diaries and get an idea of where they were buried but not an exact location. So it is also honoring the lives they gave to help make this the country we have today.

John – What are your personal feelings?

Larry – I have a great appreciation for them. It’s funny how life works out for you. The hospital where I was born was like three blocks from the Oregon Trail over in La Grande Oregon and I thought it was great fun to play pioneer at the time and they still do that over there for the kids. They get little wagons together and they take the kids out on the actual trail over there.

It’s funny how you remember that far back but I was designated to be one of the Indians attacking the train and didn’t particularly like the location the teacher had and I thought to make it a little better we’d better get some rocks so as you can imagine I got in trouble over that and that is probably why I remember that. But little did I know that it was going to lead to when I became a member of the Idaho Historical Society being so involved in the Oregon Trail. And it sort of just carried over, that memory, and then once you’ve read four or five hundred diaries and been out on the trail you can’t do anything but appreciate what they did for you and have a feeling of compassion for all these people who did this. It just makes it come to life for you and we can still appreciate that here. I still appreciate what they did for us and will do whatever I can to help preserve what we do have left so that future generations can also understand who we are as a people here and why we are like we are. Because that was a time when neighbor helped neighbor and you got along or you didn’t get along. You just didn’t make it if you didn’t get along with your neighbors.

That’s what we still need today, is learn how to get along with other people and that’s a story that will be with us hopefully until the end of time.

John – What is the uniqueness of this time period, this Oregon Trail event?

Larry – It is very unique because it is probably one of the better documented major overland migrations in history – not only here but in the world. You’ve got some in Africa and so forth with the Boars and whatever but nothing to this extent. When you have half a million people migrating west this is something that is just unique to us and our history.

Utah State University

John Crancer – Please give us a brief overview of the Oregon Trail.

Ross – I think one of the most intriguing things about the Oregon Trail is you have to remember that at the end is free land. You just have to think that that is what they are after. You can talk about religious issues, you can talk about other issues but the idea is that for a lot of these people they are running out of land in the east or in what is the beginning of the Midwest. There’s this huge area of Indian country and then there is free land – where there is water which is another thing of the appeal of Oregon, is the Willamette Valley, the stories that came back from trappers and some of the early people was that there was water there and then you have this great desert in between but it’s all about free land.

And so when people from the time of Whitman and Spaulding in 1836 really until the railroad in the 1880’s the idea is that there is a lot of land. When you have the Homestead Act in 1862 of course that brings more and more people in but the connection between the Nebraska and Oregon is really primarily about land and about moving people across a fairly hostile environment with perceived hostile people to get to this free land. But the lure of the land is what really excited people about Oregon and the Oregon country.

John – How long is the trail and what is considered the beginning and the end?

Ross – From the earliest days it would probably be the western border of Missouri all the way to the Willamette Valley. Later it moves kind of up the Missouri and then Omaha is really the launching part of the trail – both the Oregon Trail and then later the Mormon trail which kind of paralleled it across but I’d say from the first decade Missouri, from the ‘40’s on Omaha with the destination being the Willamette Valley.

John – How long did it take people to move along the trail?

Ross – A good example is if you take the Missouri part, it took Lewis and Clark a year and a half, forty years later on the Oregon Trail about five months, forty years after that by rail four days. Now it’s about three hours and you gain two back. For the Oregon bound pioneers it’s a five month journey really. About five months by wagon.

John – What are considered the prime years of the Oregon Trail?

Ross – Probably the prime years, the time when Parkman wrote his history, I would say probably the 1840’s into the ‘50’s because once you have the transcontinental railroad in the ‘60’s and you begin getting rail traffic out then the dynamic changes dramatically. So, from my perspective it would be the 1840’s into the 1850’s and then of course the Civil War is disruptive in many respects but I would probably put about 1840 to ’54, ’55.

John – But people did travel the trail quite a bit later.

Ross – Yes they did.

John – How late were there still travelers on the trail?

Ross – I’d say until the coming of the railroad, until the 1880’s. A lot of people though after would take the transcontinental to California and then move up into the pacific northwest but as you know, in Washington and Oregon the growth was on the west coast and then back to the east and then Idaho in the 1860’s but I really think that most of the overland traffic really is ending by the 1860’s.

John – What is the historical significance of the Oregon Trail?

Ross – One of the weird things I’d say about the significance of the Oregon Trail is that it created one of the best archives of personal journals comparing an experience that you could ever find. When the Oregon historical society in the 1880’s and ‘90’s decided to gather these babies up it created a great archive of what life was like crossing that trail. So that is one major thing. The other thing is just the lure of the west and the free land and getting out here and having this total experience – for most people thinking they’d never go back. It was the same thing for them as it was for their forefathers crossing the Atlantic Ocean. You make this 1,500 hundred mile, 1, 600 mile journey you are never going back. They did not anticipate rail traffic or riding back quickly like Marcus Whitman did that one time. If you were going to go out there you were gone.

John – What kind of people did it take to take on this challenge?

Ross – A lot of contemporary historians do demography and more quantitative stuff and one of the things is it’s mostly younger people. Its people with their future ahead of them, that they’ve got a life time to take this gamble and make it pay and so people who are set in their ways who already have land, they’re not going to do that very often. It isn’t gold rush, it’s land that they are after and so for the most part it is younger people. It’s people that often because of the division of family land saw no hope in agriculture because their family farms could only be divided so many ways and so it was the only way they could stay in that profession.

There are some of course who came for religious reasons. They felt a call to go out there to work with the Native Americans or what have you but I think most people were young, had their future ahead of them and really felt economically it was the only way they could get ahead and survive.

John – What were some of the bigger challenges of making this trip?

Ross- Always I think, health, animals – the safety and sustainability of the animals which in both cases depends somewhat on good food and water and then of course the perceived more than the real notion of the Native Americans. I think if you read the journals carefully there is always a fear of Native Americans and some kind of attack but in actuality it was minimal. There weren’t very many at all but I think it was always something that people thought about, talked about, wrote about in their journals.

I think primarily the sustenance. A lot of people died. If you got bad water or got any kind of infectious disease your chances were pretty slim. And then the same thing was true with the animals. And if you lost your oxen or your horses your alternatives [were] you would have to combine families, combine belongings, leave stuff behind and still keep this dream and hope going. One of the stories of the Oregon Trail was the grave sites and it took its toll on a lot of people. There wasn’t any kind of real medicine to challenge some of the diseases like cholera and dysentery, typhoid that they contracted along the way.

John – Do you have any general figures on how many people died most of them died from disease versus Indian attack or other things?

Ross – Oh, a lot, lot more from disease. A lot more. There have been some studies done that indicate numerically if people kept a good tally of who started and how many survived. What comes to mind to me was about 80% of those who started made it. That’s pretty good, pretty good success. But they went in groups. There was a protection in numbers. There was also an ability to sustain and help each other more in numbers

John – Do we have numbers on how many made this crossing? Total emigrants?

Ross – It is speculative and you can read some historians who would say as many as 75,000, others would say about 50,000 and then when you add the Mormon pioneers to it, it almost doubles it. But the Oregon bound pioneers it’s probably somewhere between 50,000 and 75,000.

John – And then you add the California travelers.

Ross – Yeah And they of course went up – at least most of them – as far as Fort Hall out to the Raft River before they headed to the southwest so they shared the Oregon Trail most of the way. So at least on the eastern half of the Oregon Trail you are talking well over 100,000 people.

John – Let’s talk about Idaho. Start with a general overview of the routes through Idaho.

Ross – If you go from border Wyoming where Thomas Fork comes into the Bear River and go all the way to the Snake on the other side of the state I think it’s about 460 miles and if you say you could make 22 to 25 miles a day you are talking about three weeks at the best of getting across there in July and August. I remember reading in some of the journals about when they first came in and hit Thomas Fork and they reconnect with the Bear River. All they talk about is the mosquitoes in Idaho, when they first hit Idaho. Being raised there I understand that. I understand I probably got drenched with DDT at nights when they would come through and spray my home town but any way…they talk a lot about the physical problems but for the most part people would stay on that trail from the Wyoming border to west of Fort Hall and then most of them stayed on the Oregon Trail. Some would leave at Soda Springs and come down the Bear River, cut across – heaven knows what they did for water and not very many did it – but then cut across to California. Most would go up the Raft River, up it toward Malta, cut down into Nevada south of City of the Rocks. Took that route, the California Trail. But most of the ones I think followed basically the Snake River to Three Island Crossing and then angled toward the Boise River and down to where the Boise reconnected with the Snake.

There were some variations after Glens Ferry and the three Island Crossing too of different routes you could get to the Boise river so there were alternatives and I’m sure everybody was always looking for the shortest route but the one thing that people realized is that their predecessors, be they the trappers who were guides, the one thing they knew was where water was and that is what you had to base it on I think – is how many days you could go without a water supply. Your animals couldn’t go very far, and how difficult it might be to find a place to water.

John – One thing in the diaries when they get along that deep Snake River canyon and looking at the water down there and that’s the frustration.

Ross – Oh yeah. Totally. It’s one of those weird things about the Snake River Plain is that it isn’t a canyon. You farm almost to the edge of the canyon in some areas and then you go down almost 800, 1,000 feet and that’s where the water is. They just couldn’t visualize any way of moving that water like they did later but you’d get – especially late in the year where the little tributary streams were dry and you could see that big river and no way to get down to it unless of course later they found some different ways but that was always one of the frustrating things I think. Any time they took a short cut that was usually a consideration. How long it would take. If you were going from Three Island Crossing to north of Mountain Home into the Boise River and you know you’ve got to do that within two days because I don’t think there is water in between. I’ve never seen any and I can remember some of the journals, especially I think it was Henry Pritchett’s talking about did we make a mistake, did the people before us make it because they are always following someone else’s route and later on they weren’t guided by people who had been there that much but just an elected kind of captain of the group.

It was a gamble. It was a total gamble even as they became more secure in the route on disease and weather and different things. I don’t think they had very many enjoyable days. But it always frustrates me still as much as I love Idaho. I never read anything in any of the journals where people liked it. Where people actually saw something there that was attractive. They all wanted to get away from what they were going through.

John – The only positive thing I heard was Thousand Springs.

Ross – Yeah, that’s a good point. You have to think of where they had been before they saw Thousand Springs. That was a Mecca, that was an oasis.

Ross – I like Bear Lake Valley but after you leave and go over to Fort Hall then going across south-central Idaho is pretty dismal until you hit Thousand Springs and that would be like a fantastic oasis. But sometimes late in the year, whether or not the springs had water in it. Of course you have to remember there wasn’t any irrigation upstream then so people weren’t damming and putting it out on the fields.

John – Talk some specifics about the Montpelier area. A little something about Thomas Fork.

Ross – Part of it, they crossed as I’ve looked at it pretty close to where Thomas’ Fork enters the Bear river and there’s kind of a natural back up there and the channel is pretty deep. I actually worked a summer construction job putting a bridge over it on Highway 30 and it is a deep channel. It’s a great fishing place. Thomas Fork is a great fishing stream but they weren’t interested in fishing. They were interested in how you get across that little ford and it was difficult and it wasn’t originally a clean embankment going down. They really went off and it isn’t that wide. It’s at best 20 to 30 feet or at worst. And they hit it at a time of year when it was after the run-off but it still was a very difficult crossing because a lot of them talk about it. It was the first one they had done for a while. They had crossed the Sweetwater but they crossed it really high.

And then of course from there right after is probably their biggest climb in a short distance that they had had on the trail in some respects and that’s when they made a choice and they were guided I think because of the swampy nature around the Bear River to leave it, take a one day journey, go over Big Hill and back down into the Bear Lake Valley and that was a good climb. I think it was really, really hard on them, a tough hill and again because of the journals they describe it pretty clearly that it taxes their animals, it taxes their equipment and even many times their off pushing to help the animals to get the wagons up over that hill.

John – Where would that rank as a challenge along the trail?

Ross – From a personal perspective I think any time you are dealing with water it’s a bigger impediment but insofar as a quick, abrupt climb until they get to the Blue Mountains of Oregon I think it’s the biggest and they had been going downhill quite a while coming across western Wyoming and I think just across that stream then move just a few miles and begin that abrupt climb which is really, unless you walk it you don’t understand how steep that is. Even if you ride a horse up it, it is very steep and you wonder why they didn’t go around the edge. But they chose, that was the path and they all followed it and it didn’t get any flatter. It just continued to plague them.

John – Later up on that hill, what are the real challenges of getting both up and down it? What makes it so difficult?

Ross – I think a big fear going up is are the animals going to be able to hold the wagon. Unless they decide to back down they weren’t going to go anywhere and that is always really, really dangerous if it starts happening so that was always a big concern. And the braking systems they had on those wagons weren’t the best. They were hand held and hand held metal on metal almost. I think it was just the challenge of the climb with animals that were tired and had been a long way and then to get off it and go down is always a challenge on the braking system because you just can’t turn them loose but it’s easier for them but you can’t let your wagon run into the back legs of your livestock and so you have people putting ropes around the wagons and having humans hold them back as it goes down off the hill. And so you get in a wagon train and pretty soon – I think one of the stories is you have to take them up a wagon at a time and a wagon down at a time and then you go help each other.

John – Was another problem the weight and what they were carrying?

Ross – When you stop and think. I don’t know if you’ve looked at the things that were advertized on what you should take. If you’ve ever moved it’s hard to throw a lot of things away but a lot of these people were young so they didn’t have a huge amount of chests of drawers and beds and things like that. They are mostly carrying food and the basic essentials. It’s really hard on them to throw anything out or throw it away but if they don’t carry it over in the wagon they are not going to get it over there so even as heavy as it is – but also they had been on the trail for two and a half months so it was a lot lighter than it would have been earlier in the trip. I just think they had to work with the hand that was dealt them. There you are in July, it’s hot, you’ve got this hill, it’s going to be tough. We’re going to work together and we’re going to take a wagon at a time. It’s going to take us all day to move all the wagons over but that’s our day.

John – Another challenge was the composition of the soil and some of the shale.

Ross – I still think it was more the abrupt nature of the climb rather than the composition but I can remember my grandfather used to herd sheep up there in the little town of Alton and there is a lot of shale which there isn’t many other places in the valley but on the one side there is a lot of shale and that could have made a difference with wagons because you’re not going to rut down. You’re not going to make it as easy because it’s slick.

John – What is the relief of getting over that big hill and getting into the valley?