River of No Return: Idaho's Scenic Salmon

The Salmon River country is the heart of what many imagine Idaho to be.

Look at a map of Idaho and you begin to see why the Salmon River country is considered by many to be the spiritual heart of Idaho. Located in the center of a rugged state, the Salmon River watershed includes the longest undammed river in the lower forty-eight, as well as the largest wilderness area in the Intermountain West.

The Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness is home to wolves and cougars, elk and deer, wolverines, bighorn sheep and mountain goats. The U.S. Forest Service estimates that the 2.4 million-acre wilderness supports 240 bird species, 77 different mammals, 23 fish species, 21 kinds of reptiles and 9 species of amphibian.

It is no easy task to be Idaho's favorite river, given all the choices. But the Salmon River and particularly its famous tributary the Middle Fork are Idaho's premier whitewater river trips. In fact, many outfitters consider the Middle Fork to be the river trip by which all other river trips are judged. The entire hundred miles of the Middle Fork is now protected in the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness.

We profile the river's storied history, including its famous hermits.

Topics

For more than 400 miles, the Salmon River winds through central Idaho. As it gathers momentum, the river passes the towns of Stanley, Challis, Salmon, and Riggins, and several other smaller communities. The Salmon River Country is not heavily populated; nevertheless, and perhaps because of that, these towns have great charm and more than their share of characters.

Stanley

It's hard not to love the town of Stanley, Idaho. At 6260 feet elevation, this community of a hundred hearty folks lies at the base of the stunning Sawtooth Mountain range, with a view of the White Cloud peaks across U.S. Highway 93. Stanley is the town closest to the headwaters of the famous River of No Return. It is situated in the Sawtooth National Recreation Area and is one of Idahos must see places.

Challis

This mile-high town got its start as a trading center for nearby mines. Mining is still an important element in the towns success. Approximately one thousand folks live in Challis, many of them connected to cattle ranching.

Salmon

With a population of approximately three thousand, Salmon is the largest town along the Salmon River. It was near here that Sacagawea was born. Near here is where Lewis and Clark first entered Idaho in 1805, and met the Lemhi-Shoshone Indians (re-uniting Sacagawea with her people) and procured horses for the rest of their journey to the ocean. The town got its start when gold was discovered in 1866, but today Salmon is a cattle town and, increasingly, a recreation center for river running, steelhead fishing and elk hunting.

Riggins

Situated on Idaho's north-south highway, at an elevation of 1800 feet, Riggins is the first town one arrives at after a wilderness float trip on the Salmon. Riggins is wedged in between high mountains steep enough to deter outward growth. This gives the impression that Riggins is one long street. Today that street, Highway 95, is filled with outfitters offering a dizzying array of whitewater river trips and steelhead fishing trips. But Riggins used to be a timber town, until the mill burned down. The bridge just outside of town on the Salmon River is the state's North-South boundary; it is here where one changes from Mountain to Pacific Time zone.

The Salmon River is the longest river contained within a single state, outside of Alaska. Along many parts of its 425 mile length, there are no restrictions pertaining to its use. If you have a raft, canoe or kayak, just jump in and begin your journey.

However, there is a section of the river -- the part most white-water enthusiasts prefer -- where usage is restricted, and permits are required.

One of these is the Main Salmon, in the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness. The other is the Middle Fork of the Salmon. If you wish to float these during the main season (June 1 through September 10) you have two options: you can sign up with an outfitter, or you can enter the Forest Service permit lottery, held each December and January. But the odds of getting a permit on the Middle Fork are now 29 to 1.

So if you have your heart set on floating a river this year, an outfitted trip is your best bet. They'll brew the coffee for you, fix your meals, and get you down the river safely.

Idaho poet William Studebaker understands the several meanings of the word salmon. He grew up in the town of Salmon, along the Salmon River, and watched the salmon migrate upriver to the exact stream where they were born, only to lay their eggs and die. Studebaker believes the life cycle of the salmon is the "hero" cycle that Joseph Campbell and Carl Jung understood, where we begin, we journey, and we return.

[From Everything Goes Without Saying, Confluence Press, 1978]

Every year they return.

They have no map

almost no brain.

They come anyway:

stealhead, chinook salmon

traveling in silence

toward spawning beds

up the clear stream

of death.

I have sat these years

rocking my soul

while the river tunes rocks

and the green voice

of the ocean plays back

a euphonious eulogy

to the waters of the world.

Everything goes without saying.

Like my fish

these lines will turn belly-up

in the headwaters

at the glacier's foot.

[This poem was written in the early 70s when I was at ISU and had just begun to develop a voice as a poet and writer. I had practiced a long time, but it finally took subject matter to bring rhythm, trope, experience and perception together. In this poem, the first 20 plus years of my life were compressed into a riverscape (the Salmon River) and from the clarity of the water a fortune is forecast. What meanings are there beyond the rhythms salmon travel in a lifetime? How could mine be more?]

This is death, you know

the instinct

that steers the salmon

out of the ocean

and drives her up stream

to a gravel bar

where she wiggles

a nest for her redd.

Having done what

she could not dream

she turns crone, withers

anchors eel-like

among river bed stone

sets her lower jaw

fish-teeth gnawing water

she's too weak to breathe.

And her roe waits for some jack

to roll the dice, to set

in motion alevin, parr, smolt--

the last good luck

for which her death

is hope.

[It is a later version of Ars Poetica, but without the allegorical implications, more sympathy than vicariousness. Another poem dependent upon my knowledge, acknowledgment of the salmons life cycle as an allegory for my life–for all of ours. The word salmon was a powerful word in my childhood: I was from Salmon which is on the Salmon river up which salmon migrated–beginning and ending a life cycle I watched with joy.]

The Salmon River Drainage

The Salmon River drainage can be divided into five distinct whitewater segments, each with its own personality and level of difficulty. The Main Salmon River has three segments that are often referred to as the Upper Salmon, the Main Salmon (the middle portion of the river), and the Lower Salmon. The South Fork of the Salmon and the Middle Fork of the Salmon are the fourth and fifth whitewater runs in the Salmon River drainage.

The Upper And Main Salmon

The Upper Salmon begins in the headwater area of the Sawtooth Mountains. This stretch of the river near Stanley, Idaho, provides the river runner with beautiful mountain scenery and moderately challenging rapids along a well-traveled Idaho highway. The middle section of the Main Salmon River runs through a deep and remote canyon in the heart of Idaho's backcountry. Here you'll find over 80 miles of river classified as Wild and Scenic. Because of the high demand to float this portion of the river, private rafters and kayakers enter an annual February lottery to try to secure a summer permit for this segment of the river. The inexperienced whitewater thrill seeker can always join a commercial outfitter for a catered outdoor experience on any of Idaho's popular rivers.

The Lower Salmon

The Lower Salmon segment begins around the Idaho town of Riggins. The river canyon on this stretch of river is more arid and open. The rock and pine tree canyon walls of the Main Salmon give way to broad expanses of canyon vegetated with sage and grasses. Where the canyon of the Lower Salmon narrows, rapids of moderate difficulty develop in three distinct canyon stretches. Permits for this segment of the Salmon River are available on request.

The South Fork Of The Salmon

Wild, remote and challenging, the South Fork of the Salmon dares the experienced river runner to test his or her skills. Kayaks and catarafts are the usual whitewater crafts chosen for this narrow, steep, and boulder-filled river that empties into the middle segment of the Main Salmon River near Mackay Bar.

The Middle Fork Of The Salmon

The Middle Fork of the Salmon River has been called the Disneyland of Whitewater. The waters here twist and churn for over a hundred miles in the mountain wilderness of Idaho. The rapids are fairly continuous and can be some of the most challenging of all the western rivers. Permits are applied for through the lottery in February. Private boaters have about a one in thirty chance to secure a permit and a whitewater trip of a lifetime.

River Difficulty Ratings

As with all rivers, the difficulty of the rapids often depends on the water flow. Springtime often brings high and fast water flow that can make rivers much more dangerous than they are at normal flows. Low water can make rapids more difficult to navigate, increasing the danger of pinning a raft or kayak on a rock.

The difficulty of rivers in Idaho is rated on a scale of class one to five (I, II, III, IV, V). Class five (V) water is often life threatening, four (IV) is very difficult and often risks injury or loss of equipment, three (III) is moderately challenging to the experience boater, two (II) usually indicates safe fun waves and easy maneuvering to avoid obstacles, and one (I) is fairly flat moving water.

The Upper Salmon is generally class II-III, the Main Salmon segment is usually class III-IV, the Lower Salmon is mostly class II-III (but has a class V rapid at very high water flows), the South Fork and the Middle Fork have a boat load of class II, III, and IV whitewater. In fact, the South Fork has several Class V rapids, too!

Running Rapids -- Gathering Information

There are several ways to prepare for running the rapids in a particular river segment. Government agencies and private publishers have created maps, books, and packets of information that locate and describe the major rapids of most whitewater rivers. Much of this information is available from libraries near the whitewater river. Word of mouth information is also valuable and can be the most current source of information. Sources include the river ranger of the administrating government agency, local whitewater retail stores, other river runners, and vehicle shuttle companies. Commercial videos of whitewater rivers and their rapids are also available for purchase or for rent from river-oriented outdoor stores.

Running Rapids -- Know What's Around The Bend

Velvet falls, a class IV rapid on the Middle Fork of the Salmon has capsized many an inattentive boater. Its smooth as velvet at times with a three-foot drop that hides its sound and visual presence. Experienced boaters always know where they are and what rapids are ahead. One way of knowing what's around the bend is by constantly monitoring your progress down the river with the aid of a river map. Staying oriented is the key. Once you lose your position it is much harder to determine where you are.

Identify major drainages coming into the river and easily identifiable landmarks like historic buildings, trails, bridges and general land features. If you are technologically oriented, you could even use a GPS position locator. More practically, use you watch to determine your position. Time your first half hour and hour of travel. Note where you are and how far you have traveled each time. If you went 1.5 miles the first one half hour and another 1.5 the second half hour, you have a good estimate that your progress in similar water flow for the next hour will be 3 miles per hour. At a rate of three miles per hour, you'll be real close to Velvet falls (around mile five) in an hour and forty minutes from the start of your Middle Fork trip.

Running Rapids -- Scouting

Unless you are an experienced river guide, all class IV and V rapids should be scouted for the best route and for potential dangerous obstacles. Even class III rapids should be scouted if you are not real familiar with them. Pull out well above the head of the rapid on the side of the river that gives the best view of the rapid. Hillsides are great for seeing the whole rapid, but a walk down along the river gives you a real life view of what to expect at water level.

Plan your route through the rapid. One useful technique is to determine where you want to be at the end of the rapid and then back plan your route to the top and where you want to enter the rapid. Where you enter a rapid and how you position you craft at that point is often the critical moment in a successful run. If you start out poorly, things generally don't get any better for the rest of the run. Have your route through the rapid memorized. Visualize yourself going through the rapid making all the required moves to follow your planned route. Use landmarks that are readily identifiable from water level to note your progress through the rapid, or to identify when you have to make critical moves. If you can't quite figure out a safe route, odds are that if you wait a while someone else will come along and run the rapid before you and show you an acceptable route.

Running Rapids -- Ready, Aim, Fire

Running a scouted rapid is 90% preparation and 10% duration. If you've done the scout well and the rapid isn't outrageously difficult, you merely follow your plan to a successful run. River runners often scout for a half hour and then run the rapid in a minute. Of course the boater has to have the skills to make the craft do what is necessary to get through the rapid. Here again preparation is the key. Whenever you can, practice doing difficult maneuvers in easy rapids to build your skills. Know how to avoid obstacles, and what to do if you are about to hit one. Learn how to spin off rocks, high side, punch through holes, ferry, and catch eddies. And if you are a beginner, always follow the route of the boat in front of you if they make a clean run.

May the force be with you and may the river gods bless you with good luck and safe boating.

(Idaho river runner Jim Acee prepared this report on how to scout a rapid.)

Friday, August 23, 1805. The river...is almost one continued rapid...the passage...with canoes is entirely impossible... My guide and many other Indians tell me that the...water runs with great violence...foaming and roaring through rocks in every direction, so as to render the passage of any thing impossible. Those rapids which I had seen he said was small and trifling in comparison to the rocks and rapids below...and the hills or mountains were not like those I had seen but like the side of a tree straight up. --Captain William Clark.

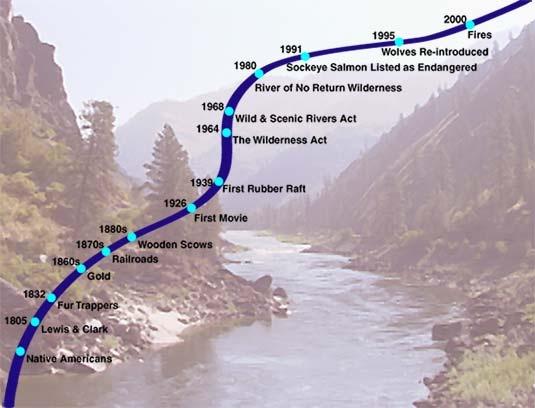

The Salmon River entered the American consciousness through the journals of Lewis and Clark. Almost immediately upon seeing it, Clark realized that his comrades had no chance of surviving a trip in canoes. This realization prompted Lewis and Clark to take the advice of Native Americans and head north on horseback, through Montana's Bitterroot Valley, to cross Idaho along the Lolo Trail of the Nez Perce.

Lewis and Clark never returned to the Salmon River. It had dashed their hopes for a water route connecting America east and west.

But these days people flock to the Salmon River to raft, kayak, and canoe the famous River of No Return. They come to experience the very wildness that turned back Lewis and Clark.

Each year, close to twenty thousand people raft the main Salmon and its famous tributary the Middle Fork.

The Salmon River Country is the heart of what many imagine Idaho to be.

Look at a map of Idaho and you begin to see why the Salmon River country is considered by many to be the spiritual heart of Idaho. Located in the center of a rugged state, the Salmon River watershed includes the longest undammed river in the lower forty-eight, as well as the largest wilderness area in the intermountain West.

The Frank Church River of No Return wilderness area is home to wolves and cougars, elk and deer, wolverines and big horn sheep and mountain goats. The U.S. Forest Service estimates that the 2.4 million acre wilderness supports 240 bird species, 77 different mammals, 23 fish species, 21 kinds of reptiles, and 9 species of amphibian.

It is no easy task to be Idaho's favorite river, given all the choices. But the Salmon River, and particularly its famous tributary The Middle Fork, are Idaho's premier whitewater river trips. In fact, many outfitters consider the Middle Fork to be the river trip by which all other river trips are judged. The entire hundred miles of the Middle Fork is now protected in the Frank Church wilderness.

Over the years, the Salmon River Country has rebuffed attempts by railroad officials to punch train tracks through the heart of it, survived numerous proposals to dam parts of the river. During the Depression of the 1930's, the boys of the Civilian Conservation Corps began building a road through the country, but World War Two put a stop to that. For now, the wilderness status afforded much of the Salmon River Country will keep the “heart of Idaho" wild and free.

River Journals

1999

Dear Paddling Pals and Adventure Lovers,

I've returned from another great river adventure and thought you might enjoy hearing the tale (a 5 day and 4 page saga). The cast of characters includes "Canoe Ken" Wiesmore, Ted Thomason (Cat Skinner and Pirouette Portager), Kurt Bouman (Gear Jammer), and Yak (kayak) Surfing Masters Jon Wheeler, Travis Bailer and Steve Vacendak. (Travis and Steve were -- luckily! -- fellow students with me in Les Bechdel's white water rescue class last March.) Our snow launch on Marsh Creek was noon last Thursday, May 21, with the Middle Fork Lodge gauge at 4.2, a couple feet of snow on the ground, and a warming trend on its way: Ken had timed his permit application to try to catch the high water and hit it just right.

Marsh Creek started out docile enough but rapidly picked up to be a very fast stream with a 54 fpm gradient and a fair amount of down timber. I quickly recognized my limits and gratefully hopped aboard the gear raft with Kurt, where I was put to good use pushing and pulling the loaded raft off the rocks it frequently hung up on. Meantime the yakers didn't waste a moment but got in some nice long sledding seal launches from along the canyon-side avalanche chutes.

We arrived at Dagger Falls about 5 p.m. and decided to portage the rafts and take advantage of the outhouse equipped campground. and the Yak Masters decided it was a great opportunity to run the falls twice -- once in the evening and again the next morning (everyone who's seen the photos, says "Wow! Those kayaks sure look small".

After a cold, rainy night (brightened by a distant haunting melody from Jon's penny whistle), Friday dawned clear and started the warming trend that was with us for the rest of the trip. Knowing that the day held Sulfur Slide, Velvet Falls, The Chutes, and Powerhouse, I happily served as raft navigator and occasional oarsman since Kurt had injured his eye during the portage (and he inspired my rowing with harmonica blues).

One of the great benefits of an early season trip is not having to compete for campsites and hot springs. We started our hot springs tour of the River of No Return Wilderness with lunch at Trail Flats, where the pool on the rocky river bank is just deep enough to submerge those sore shoulders. A nap after lunch would have been very nice, but thoughts of Powerhouse and Pistol Creek ahead and the by now obviously rising river kept me alert. The tight S turn on Pistol Creek Rapid -- barreling toward the wall -- was a real thrill on the raft. The strong eddy currents kept Ken busy as he tried to photograph us coming through ... but not as busy as Steve who we later learned decided to make a swimming descent (the yakers had been lagging way behind, in Surf Heaven).

We made it to Indian Creek Guard Station by beer thirty and enjoyed another outhouse equipped camp -- this one with a $2000 Clivus Multrum composting toilet. Ranger Rick (yes, really!) welcomed us while we filled our water containers and the next morning we were thoroughly inspected for the required fire pan, dishwater strainer, port-a-potty, shovel and (be sure to note this, David) bucket. Our morning camp also included a demonstration by Jon of the twirling bucket method of coffee grounds settling, quite an impressive feat (though threatening to the feet!) The outhouse was very nice, but Indian Creek has (during summer season) the 2nd busiest airport in the state next to Boise so I wouldn't recommend it as a camp of choice.

Saturday offered several miles of "flat water" paddling, but with the river up to 5.2 I got some excellent experience with strong eddy lines and choppy waves. Ken taught me lots about reading the water, spotting holes and sneaking inside corners which also helped my confidence. At our Marble Creek Rapid scout, I enjoyed a visit with 6 women who'd flown in to backpack from Indian Creek to Loon Creek, and the guys had a Surfing Safari. We savored another hot springs lunch at Sunflower Flat with its series of pools thick with Johnny jump-ups and hot shower cascade into the river; then hopped on down river to Whitie Cox Camp where we left on dry suits to protect us from the hot spring's mites (hot springs in dry suits?), and admired the pile of antlers and flag on the infantry-stone marked grave site.

Saturday night landed us at Big Loon Camp, justly famous for its hot spring. While everyone else focused on dinner, I snuck off for a hike to the springs and a solitary soak. The mile trail up Loon Creek was thick with wildflowers: balsam root, violets, phlox, woodland star, and wild clematis (a blue mystery flower suggesting a shooting star). and the massively planked spring on the banks of the creek, overhung with blooming service berry and with snow covered mountains in the distance, was one of the most beautiful I've ever visited. Walking back along the adjoining Simplot Ranch pastures I was treated to a large herd of elk as well as having to wind my way through grazing draft and riding horses. The springs were so wonderful that we all took several warming soaks before heading out the next morning.

Sunday we skipped the last of the Middle Fork hot springs at Hospital Bar (it was under water), but stopped to admire the Tappan cabin at Grouse Creek (graciously left open by the Bob Simplot family for river travelers to visit). Huge lilacs overhung the cabin, thick with swallowtail butterflies and blossoms perfuming the air, and Grouse Creek happily tumbled down a rocky wooded glen behind it. The homestead radiated the beauty and solitude that must have drawn many pioneers to this river and it was hard to pull myself away from such a magical place. But Tappan Falls called and our river adventure flowed on.

After an exciting but uneventful run of the four Tappan Rapids, we were ready for a lunch break at Camas Creek Camp. This steep creek sorely tempted Ken, our Class V canoeist, but he settled for a hiking scout on this trip. A climb up the steep hillside rewarded us with spectacular views and lots more desert wildflowers including hot red fire cracker penstemens as well as lovely blue ones, and fragrant sagebrush. We also stumbled on the interesting remains of a horse with a bullet hole through its forehead; the hoofs were collected as souvenirs and their odor discretely moved from raft to cat as the trip progressed.

The river was now up to about 5.7 on the gauge (5,740 cfs and graded as hazardous) and that was before the added volume of all the creeks below MF Lodge: class II rapids had substantial waves and we were finding whitewater where none is described in the books. Haystack, the first of the really significant lower rapids still lay ahead of us so we rousted out Travis, who had turned into Rip Van Winkle worn out by too much surfing (is there such a thing as too much?), and headed on down the river. After a brief stop at the Flying B Ranch for sodas and a phone call (civilization!), we scouted Haystack which has gone up in class since a slide several years ago. We found a good line and got views into its raft eating holes from a fairly comfortable distance.

Survey Creek Camp was our last night on the river and our first night to use "The Groover," named for the marks it leaves behind (on yours). The camp lies below a sweeping sagebrush plateau with views back up into the high country and deer grazing unconcerned with my attempts to get close-up photos. We got a good night's sleep in preparation for the final day's challenges with nightcaps of Ken's Hot Peppermint Patties (hot chocolate with peppermint schnapps) and more blues harmonica from Kurt.

Monday started with a great pancake breakfast and search for our river markers which were buried by the rapidly rising water -- the river gained about .7 ft overnight! Our first stop was Waterfall Creek shaking the ground with the force of it's tumbling water and creating rainbows across its bridge. Ken's canoe had developed a stress fracture so he did some boat repair and we continued on. Veil Falls, our next stop, is one of those places where you can enter the heart of the world: a large cavern behind the falls is marked with pictographs by earlier river travelers and graced with forget-me-nots, junipers, and a perfect bonsai tree. Swallows dance against the sky, and the water weaves patterns of lace as it falls. Another place hard for me to leave.

The river continued very busy with time for only a glimpse of bighorn sheep high on the cliffs above us. Our lunch at the scout for Redside Rapid didn't lend itself to large appetites. Redside looked nasty and was. Ken and Ted chose the left side and had good runs. Kurt and I made it through the main drop on the tongue, but then met a wave that munched the fully loaded gear raft as a light after lunch snack. Ted got to us really quickly and we were out of the water in less than 2 minutes, but Captain Kurt jumped back onto the overturned raft with hopes of landing it before Weber. Meanwhile, the cat is getting surfed on another big wave and I'm wondering if I've gone out of the frying pan and into the fire. Things settled down for a moment and I got a throw line to Kurt (a bit short and I'll be working on my throw). We hit Weber, though, before he could do anything with it and he had to turn loose facing the next nasty rapid on an overturned raft and with only a paddle for navigation. Somehow we all made it through ... all I remember is a blur ... but it took us almost another 2 miles to get the overturned raft eddied out, with Kurt paddling like crazy in the fast water, and everyone else pushing the raft with their boats. All that z-drag practice was put to good use, and we got the raft flipped back over surprisingly easily (easy for me to say -- with 6 guys, my job was getting photos). and we were really lucky -- besides a chewed up oar, the only losses were tools in the ammo cans (which had their lids ripped off) and my "boutique" throw rope, not designed to be used as a serious tool.

The rest of the run out we approached with caution -- it was continuously fast and busy, with the size and complexity of the waves only increasing at the named rapids: the two Cliffsides, Ouzel, Rubber, Hancock, Devil's Tooth, House Rocks, Jump-off, and Goat Creek. About 5:30 we made it to the confluence and were surprised (and maybe a little relieved) to see our rig waiting there instead of at Cache Bar, another 4 miles down the Main. The drive out allowed that gradual transition from the continuous present of being on the river, through lowering adrenaline levels, and into beer and fresh green food in Salmon. The Twin Falls boaters pushed on home and to work the next morning; the unemployed of us (all the kayakers, of course) camped under a no camping sign on the road to Stanley Lake and continued on home the next day.

This was my first high water trip and I've gained a lot of respect for the magnitude of change that can occur on spring rivers. It was a treat to be on the Middle Fork before the busy tourist season (we saw only 2 other small groups), to be there during the gorgeous unfolding of the spring wildflowers, and a privilege to learn from and be inspired by the skill of excellent boaters and to enjoy the company of people who love the wilderness. It was the perfect start to my 2nd year of boating, and I send special thanks to Ken and my fellow adventurers for helping me get to dance with this magnificent river.

1995

The Middle Fork of the Salmon River in Idaho has been called the "Disneyland" of white water rafting. On our trip in 1995, my wife, Annie, and I learned that the term "Disneyland" doesn't come close to describing the experience.

The Middle Fork is the major tributary to the Salmon River. It begins in the high meadow country in central Idaho, near the town of Stanley. The portion that is normally floated is a 97 mile section from the "put-in" at the Boundary Creek Campground (elevation: 5700 feet) to the "take-out" at Cashe Bar, three miles below the confluence with the Main Salmon (elevation: 3015 feet). This 100 mile, seven day trip is all within the Frank Church – River Of No Return Wilderness. On the Middle Fork section, there is very little development, a few "fly-in" lodges are the only sign of human habitation. At the half way point of the trip, the closest road is 50 miles away.

The first step in making a trip down the Middle Fork is to secure a permit. Due to the popularity of this river and to preserve the wilderness character of the area, a very limited number of permits for private floaters are available each season. The most popular times to make the trip are during the first three weeks of July. This is after the dangerously high water flows of the spring run-off, but before low flows of summer make the trip impossible.

On our annual Spring float trip on the John Day River in 1995, a friend who we often raft with asked if we had any plans for the 4th of July. We said we didn't, but were open. He said, "Well, you do now. You're invited to my 4th of July river party on the Middle Fork!" We had seen pictures of the Middle Fork and read about it, but had never really thought we would be able to make the trip.

SOME BACKGROUND My wife and I began floating whitewater rivers as a hobby in 1983. We rented rafts and other gear and floated the Deschutes River in Central Oregon. We met other people who enjoyed the outdoors in general and river rafting in particular, and soon were part of a group that floated together. We bought our own raft in 1992, a bright yellow 16' self-bailing boat, with "dry boxes" to store and transport gear, and an aluminum rowing frame. We floated increasingly difficult rivers to gain experience. In a few years, we had floated all the major Northwest rivers (Rogue, John Day, Main Salmon, and others) but not the Middle Fork.

Most "wilderness" rivers have a limited entry permit system. Applications are submitted in the winter for the summer floating season. The drawings are much like a controlled deer or elk tag drawing. The group of friends we raft with decide on dates when we want to go, then all put in for the same date. This "loads up" the odds in our favor, as the party size is about 20 people on most rivers. If one draws a permit, we all get to go.

In most parts of the U. S., rapids are rated on a numerical scale from Class 1 (very easy, small, regular waves, little maneuvering required) to Class 6 (extremely difficult, life threatening, very large waves and hydraulics, extremely technical, difficult maneuvering in heavy water required). This seems like a simple enough system, but whether a particular rapid is a Class 3 or a Class 4 is a judgement by the person who rated it, and also varies greatly depending on water flow. A rapid that is a Class 3 at "normal" flow may be a Class 5 at higher flows.

The Middle Fork has rapids that are rated as Class 3's and 4's during normal flows of 1000 to 2500 cubic feet per second (cfs). The guide books recommend floating the Middle Fork at flows in this range. Flows of 2500 - 4400 cfs are considered "moderately hazardous". Flows of 4400 - 6500 cfs are ranked as "a significant threat to life", and flows of over 6500 cfs are ranked as "suicidal".

THE TRIP

Our party, sixteen hardy souls ranging in age from 10 to 63, arrived at the Boundary Creek Campground and boat ramp on June 30th, the day before our scheduled launch date. The river was at 5.1 feet on the gage, which translates to a flow of 4590 cfs, just barely into the "life threatening" range. The water temperature was 44 Fahrenheit. Did we really want to do this? We had purchased wet suits at Stanley earlier in the day on the advice of some of the professional guides, who said they wouldn't consider running the river at that level and temperature without them. We soon found that it was money well spent. It was with a great deal of apprehension that we slid our boat down the 100-foot pine log launch ramp and into the water of the Middle Fork.

The first rapid is only about 50 yards below the launch ramp. At that flow, I only had a few seconds to decide which channel to take and get the boat lined up on the proper chute, as the river was moving at about 10 miles per hour. I managed to hit the slot exactly as I intended, and thought, "Maybe this won't be so bad, after all. Only 340 classified rapids to go!" The upper 20 miles of the Middle Fork has an average drop of 42 feet per mile, has 10 major (Class 3 or higher) rapids, and at this flow, can only be described as SCARY! We made it successfully through Hell's Half-Mile, Tepee Hole, Sulfur Slide, and Rams Horn with no problems, but with adrenaline levels off the scale. Then came Velvet Falls. Velvet is an 8 foot waterfall, a solid Class 4 drop at any flow above low water. On this day, it was at least a Class 5, and much worse than anything I had ever run. At normal levels, the route is to pull hard left, tuck in behind a large boulder, and drop over a 4 foot high ledge into a calm pool below. Even with the added adrenaline, I couldn't get pulled into the slot behind the huge boulder. I told Annie, "Honey, we're going to get wet!" and hit the very middle of the falls. The boat dropped into the hole at the bottom of the waterfall, completely submerged, and washed me, still holding onto the oars, out of the back of the raft. I can remember looking up through a mass of bubbles and thinking, "Hmmm. So this is what the bottom of the boat looks like to the fish". My life jacket popped me to the surface in a few seconds, which only seemed like an hour or two. Disneyland ride? I don't think so! I swam over to the bank of the river and got my feet on dry land in time to see my upside-down raft floating merrily down the stream. Sometime between the time I washed out of the boat and the boat flipping, Annie was also thrown out. She was picked up by another boat in our group about a mile down stream. The person who had the float permit and the leader of our group rescued me, and we took off down the river to try to catch our boat before the next big rapid. We caught up with it a couple miles below, none the worse for the experience except for a little water in the "dry" boxes, and missing a small bag of miscellaneous gear. With considerable help from the rest of the group, we got the raft upright and continued down to our first night's camp. At this point in the trip, two thoughts were in the front of my mind. First, I'm sure glad we bought these wet suits; second, we still have 20 major rapids to run.

The next day, we ran two more Class 4's, Powerhouse and Pistol Creek, with no problems, and slept a little better that night. Day three was mellower, with only Marble Creek and Jackass Rapids, both Class 3, to navigate. Camp that night was at Hospital Bar, a hot spring camp. The 100 water in the pool next to the river did much to soothe muscles and nerves. The only big rapid the next day was Tappan Falls, a Class 4 that was much easier than I anticipated.

The next day was a "layover" day. We stay in camp, go fishing or hiking, repair equipment, or just relax. We also have a theme party the first evening of the layover, and the theme this year was "Hippie Night". Everyone vies for the most realistic or outlandish costume, and that year, I won, hands down. (If you're ever in my office, the pictorial proof is hanging on my wall).

The last two days on the river were exciting with the same high adrenaline levels of the first, but no more unscheduled swims. We ran many more Class 3 and 4 rapids, including Rubber Rapids (one of the 10 biggest drops in the country) with no mishaps.

It is difficult to put the Middle Fork experience into words. It is one of the most beautiful places on earth. It has excellent fly fishing, exciting whitewater rapids, hot springs, ancient Native American pictographs and camp sites, and solitude in the largest wilderness area in the continental United States. If you ever have the opportunity to take this trip, you will never forget or regret it.

1997

It was quite a trip, we were all fairly experienced- 3 WWIIs (15.5ft), 2 WWI-stretched, 1 14 ft cat, 1 16ft cat, and 3 Kayakers. Had some 14 ft boats wanting to go but did not let go, as we felt too small a boat for that water. We also required helmets and wet/dry suits.

Just days before we launched, the trip was questionable as the river was 9 ft and rising - projected to be over 11 ft. We kept our plans on schedule but prepared to cancel, even at the put in, if either above 9 ft or 8 ft and rising. We put in at Marsh (actually Cape Horn) on May 21st as the road to Boundary was closed. The flow was 8.04 and dropped from high 8s the day before. The forecast called for high 7s to low 8s throughout the remainder of our trip. Marsh, as expected, was wild and fast (only four eddy spots, five if you have a cat). None of us in the party did this section before. Safety always being first, we:

- chartered a plane and flew over it a few days prior and scouted Marsh from air

- had topo maps of Marsh area

- made many calls to gather as much info as possible on Marsh

Marsh was full of fast water, blind corners and surprise holes. We had to line our boats under the first bridge (500 feet from road)...just barely fit. The second pack bridge was ok but was around a fast corner and had to duck (one guy nicked his head - thank God for helmets! Once on middle fork but above Dagger (about 6 miles), the river makes a hard right turn. Third boat started a wrap then flipped at the top point of the island just as river cut right - tight pull turn. One guy stuck on island, one guy swam. Second to last boat also got stuck same place but able to push off but had to go left of island through a mine field. Sweep boat (cat) was behind stuck boat. Between keeping eye on stuck boat, trying to find eddy, read river, and kayaker without a paddle telling him he had a swimmer down stream; he didn't observe previous stranded passenger stuck on island from previous flip. Sweep did capture swimmer about an hour later and a mile down stream (first catchable eddy) from island and shortly after caught up with first half of group - they already had swimmer's boat righted in fairly weak eddy (i.e. strong current)!

We ended up with half of party at Dagger and half camped 2 miles above Dagger too late and tired to make Dagger that evening) and a guy stuck on an island (no boat and he already paid). For the first three to four hours, we thought there was a good chance we lost him! Then, at Dagger camp, once we pieced all the information together between groups (sweep guy and kayaker talked to both parties that day...we brought radios for just such an emergency but could not get reception), we were confident that the lost guy was stuck on the island 5 miles back. Now the confidence that he was on the island varied from "done-deal" to " more than likely guy is dead" within the group.

While at Dagger, that first half of the party was also concerned about the second half as they were to have been to Dagger that evening as well. However, they were confident they pulled over and did not run into problems as they were well seasoned boaters. The Dagger party had three very experienced and able hikers head upstream with rescue gear. They first came across our other half of the party bedded down on a camp trail 2 miles above Dagger, welcomed news for all. The rescue team then proceeded on. They shared with the rest of us the feeling of despair and fear of losing a comrade while hiking up the 5 miles. Some of these hikers were ones on the side of having less confidence that he was safe on the island. Now, who's to say which state of mind is correct between the two. This is where groups are at their best! The confident ones (maybe just hope at times) keeping the worriers from losing hope and the worriers kept the non-worriers from being too complacent. We respected each person's mindset on this and as a team pulled together. As the rescue team got closer, the stranded islander suddenly heard a faint whistle in the back ground...what a relief and a burst of hope as the sun was settling down for bed. Soon, the rescue party shared the same joy when they heard the return voice acknowledge the whistle (each party should have a whistle, not just the captains). What was then like an eternity, shortly thereafter they found our guy on the island as hoped and prayed for. He was calm (as reasonably can be expected), had dried his clothes, set up a "small camp" with pine needle mattress and all the other comforts of the outdoors found on a remote Island....No, we did not give him the nickname Gilligan. The rescue team set up a line, pulled him off and had him back to camp around 3 AM! What a day!

We made the judgment to spend an extra day at Dagger. By the time we had the rest of the party portaged, it would be late, we would be tired and still a little "nerved" from the previous day, so we made the call to stay over. Although the whole river deserves respect, the section from Boundary to Pistol deserves more respect than one gives the god-father! So, with safety first, we spent the day playing horse shoes, cards, and making the load lighter (beer is not light...). The first night at Boundary we "bumped into" and visited with a group of Cater's as well as shared some dinner with some kayakers (a separate group). These two put-in the day we stayed over. Here is a story on the web about these two groups:

Dan Wagner, 45, a cat-a-raft passenger from Pocatello died on the Middle Fork of the Salmon on May 22nd. The following information has been gathered from e-mail and rbp posts. Actual events may have varied.

The flow was 7.7' as the group put on at Marsh creek. Apparently a cat-a-raft with a single oarsman flipped in Murph's Hole 1.2 miles below Boundary Creek. (This is where a sweep boat flipped in 1995) The oarsman was rescued and two boats headed down stream to recover the gear. The lead cataraft with 2 people on board flipped just above Velvet, both swimming Velvet in life jackets. The oarsman swam to shore while the passenger floated on. The body was spotted by an individual on their deck at Pistol who then radioed the Ranger at Indian Creek. The Ranger and a pilot were able to pull the body out just at the end of the Air strip. The flipped cataraft was found around Dolly Lake (a huge eddy) at mile 19 in very bad shape. This is where the group spent the night not knowing the fate of their friend. Four kayakers joined the group that night at Dolly Lake.

The victim had all of the correct clothing for a cold water trip, but was in the extremely cold water for 2-3 hours floating to Indian Creek.

If we could have changed one thing: we agreed we went down Marsh too heavy. We were fore-warned to go in light and fly some stuff in to Indian creek. We had the flights budgeted and planned for, but we were a little exuberant when loading the boats. Even once loaded, we considered unloading some and flying in but, at the flip of a mental coin, we choose to go on. Fortunately for us, all turned out well.

The trip from Boundary was as expected - wild. Careful reading of the river and proper oaring would seem to make the difference here. It was almost non-stop and fast. We actually went left of the rock at Velvet, save one boat went just right and did OK. Rest of the way was fast, big waves with nothing jumping out as critical - but that is usually the case when you either luck out or read and run correctly...or both. Pistol was washed out but was a big wavey-whirpool.

I recall seeing a camped group at I believe Dolly Lake and was surprised they had not budged yet (must have been shortly before noon). The camp seemed quite somber, could sense something was not right. After hearing what happened, was surprised they did not flag us down to send word down and see if we found anything...However, I can feel for them and the state they were in - having a missing guy and not knowing where he is.

We reached the ranger station at Indian Creek for lunch with Ranger Rick(one of the better rangers on the river). There we learned of the fate of the party before us. We had the 16ft cat and its driver fly-in and meet us there, but we were supposed to be there a day earlier...so we were late as far as he knew. Well, he helped Ranger Rick pull the body in. Imagine the ordeal he had when the Ranger pulled him over and asked him "is this any of your friends you've been waiting for?" Our guy told us the victim was a big/tall guy, maybe around 200-240lbs, 6ft-plus. He was in "perfect shape", even his sunglasses were on and unbroken.

We headed off from the station after getting checked out and camp sights assigned. Being the early season, we were surprised we did not get the camps we wanted (the other parties were willing to share the good ones with us - true generosity). Again, the rest of the river moved fast as expected. Most of the named rapids were in hibernation and could not be found. On the other hand, there were lots of big and huge waves where still waters lie at lower flows. As expected, the two rapids which deserve the utmost respect at high flows were hay-stack and lower-cliffside. Haystack was wild with huge holes. I just kissed the edge of one - it didn't have my name on it but it did have my initials. We had one boat lose a guy but got him back in shortly. Haystack at 6.8ft last year was a lot more frothy than this time. We ran left and worked towards center. If my memory serves me correctly, we should have started out a little more left. I heard the right is not bad at 8ft but without scouting, I went with what was tried and true. Just below haystack, we hit Jack Creek. This section was wild! huge roller coasters, mile after mile. Some of them had to have been over 25 feet from trough to peak. Felt like being on the ocean in high waves! Lets see 6-flags come close to this one!

Redside had some interesting waves and Webber was asleep. Lower Cliff-side was also less frothy than last year and the holes were well defined...and huge! Well, found the hole with my name on it. I was running sweep, last day, rest of the boats hugged the left wall as planned, so I had to venture next to the hole for some action...and revenge for flipping my friend last year. Well, the hole grabbed me, spanked me and it put me upside down under the cat still in my seat...or next to it before I had a chance to get scared. Got on the bottom, eddied, flipped back over with a little help from friends and off we went...not much dead time.

Shortly after that we came to Rubber. After our kayakers set up, with there not being a decent scouting point, and seeing it last year at 6.8ft, as well as not wanting to sit around after just flipping, I jumped on to rubber right down the middle and the rest followed (if I was driving a boat rather than a cat, I would have scouted first). We all did fine and got some big air. Compared to last year, the middle was more run-able this time. Last year at 6.8ft, the left had a nice shoot with 10-15ft rollers and the center was over 25ft with poppers! This time, the left seemed not to be there and the center was a big roller coaster without any poppers. Rest of the way down was washed out. Again last year, there were quite a few holes to watch for. This time it was just float on through.

All on all, we enjoyed ourselves and had one of those trips you're glad you did, can talk about, but hope not to experience again (...The Marsh experience and death in front of you...). In short, if you do the Middle Fork at high water; make sure you have a big boat (nothing less than 15ft, and more so, big tubes), read the river well (spot holes early on), respect the river, and be in a group that knows its limits.

After successfully running what we did, part of you, at least me, wants to believe you can all but walk on water. But, when you see things like what happened both just before our trip and afterwards as well as the potential for what almost could have happened to us, it brings you down to earth and sobers you quickly. It re-enforces in me that although you might be greatly skilled, the river always deserves respect, and good fortune goes to those who sow it.

2000

Joe Corlette banked the Cesna 206 so that my window was facing right down at the mountainside opposite Pistol Creek on the Middle Fork of the Salmon River. I almost lost my cookies. No, make that my hashbrowns and eggs from breakfast. What was worst than the slight nausea in the pit of my stomach, was the piercing pain in my heart when I got the first glimpse of what forest fires had done to my beloved Middle Fork. The mountainside opposite Pistol Creek was charred. The soil was black and gray. A sooty dust was being whirled around by a breeze. The once green pine and fir trees looked like licorce sticks sticking up from a mountainside that looked like it was covered with tar paper. My beloved Middle Fork. What had happened? A bluish, gray smoke smoldered from a few of the snags. Pistol Creek is one of the most popular campsites along the Middle Fork of the Salmon River. Oh, how I remember it from past river trips. River runners vie for the campsite, which has a great beach and giant, shady pines. But even though the eastside of the river was nuked by fire, the campsite on the westside was still intact. The huge pines and beach weren't in that bad of shape. Thank the river gods.

My first visit to this central Idaho wilderness was in 1977 when I floated the Main Salmon River with outfitter Dave Mills. Mills turned me on to a life of river running. I was a greenhorn kid just barely in my 30s. The Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness wasn't a designated wilderness yet. It was still called a Primitive Area without the full-bore protection of wilderness. It has always looked the same since that day when I was born into a life of river running. I've been floating the Middle Fork of the Salmon since the mid-‘80s and have grown accustomed to it being the same every float season.

Katherine, Rocky Barker, the Statesman's environmental reporter, and I were on a mission. It was a five-day trip on the Middle Fork in early October to see just what the heck the fires had done to the Middle Fork, a stream loved by wilderness travelers worldwide. We were lucky. Three river experts with the U.S. Forest Service were going with us. Ken Stauffer, Norm Ando and Dave Sabo, all avid river runners, flew in to the backcountry airstrip at the Indian Creek Guard Station the night before. Here we were just about to land. It was going to be a quick float trip, pushing about 70 miles in five days at a very slow, low flow. Normally, the run on the Middle Fork is about 100 miles. That's if you start at Boundary Creek, where the only road comes in. But we had to cut about 24 miles off the trip because the upper part of the river was too shallow. Anyway, the big fire damage started at Pistol Creek, just upstream from Indian Creek.

We Arrive at Indian Creek

Joe banked the plane and headed for Indian Creek.

Indian Creek is only a few miles from Pistol Creek. We were there in minutes.

"We can land," Joe says, banking his Cessna and approaching Indian Creek from downriver. The plane drops. We all are relieved. The Forest Service rafts on rigged and ready to go.

The Cessna's wheels bounce along the dirt strip. There it is. The Indian Guard Station. It survived the fire. In fact, much of Indian Creek survived. There was some sagebrush burned in front of the Forest Service guard station but it looked pretty good. Six deer browse through the area, only about 10 to 20 feet from the guard station. They are taking advantage of something in the burned areas, maybe the salt or something.

It's 11 a.m. and I still can't take my eyes off the opposite bank from Indian Creek. The east side of the river is black with black sticks poking up against a blue autumn sky. Ponderosa pines with brown needles portray a story to come. Soon the pines will die, fall over and possibly slide into the river and be washed away into a logjam, someplace downstream. It's all part of the wilderness cleansing and rebirth. On our side of the river, fire burned fingerly throughout the Indian Creek launch site. The launch ramp was saved but a few black stumps decorate the beach below. The black ground will turn to green next spring as new shoots will emerge toward the sun in the spring. A rebirth will take place, ever so slowly. OK, it's time to launch. Indian Creek is at River Mile 24.7. We make our way downstream and I immediately learn what to expect. Low water. Rocks. Bumpy and grinding for the next five days. Golden-brown pines, black sticks and black stumps, all remnants of the summer's fires, can be seen for several miles downstream. But this area below Indian Creek has burned before. There is evidences of old fires and rebirth.

The day goes on and we pass under the Indian Creek Pack Bridge and things are starting to look a little more green. There isn't much evidence of fire. I'm worried. The river is low and all I'm doing is dodging rocks in my kayak. The rafts simply slip over some of the rocks or bounce off others. If I hit a rock, I might get broached and cause a delay if everybody has to get me off. So, I continue to watch for every hidden obstacle in the river. There's no time for fun, like surfing small waves.

The Forest Service rangers didn't like having one kayaker along. Kayakers should travel in pairs for backup It's difficult for a raft to get to a kayaker that's in trouble. But I wanted the flexibility to move all over the river with my waterproof camera and get the shots I wanted for my slide show. So far it's working.

Sunflower Flat Unchanged

Mile after mile, my favorite Middle Fork remains unchanged. The fire hadn't reached this part of the river.

At River Mile 32.6, we hit Sunflower Flat, a very popular hot springs on the river. It's a good place for lunch and a chance to head up to the upper hot springs and see if it is the same as when I ran the river in 1998.

It's a magnificent hot springs that cascades over a rock ledge to the river's edge. You can take a hot shower if you want.

The hot springs sits on a bluff overlooking the river. There's a backdrop of the cliffs on the other side of the river with granite rocks and interspersed pine trees. White rocks are piled around the hot spring in a giant circle. Nearby is the grave of Whitie Cox, a Middle Fork icon. On his grave are piled weathered, bleached deer and elk antlers and skulls. It must be some tribute to the Middle Fork pioneer.

We continue downstream. It's the old Middle Fork I remember.

Hunting Unaffected by Fires

That afternoon, we meet elk hunter Jeff Hull as he crosses the Middle Fork on a pack bridge at Thomas Creek, below the Middle Fork Lodge. By the way, the Middle Fork Lodge is as beautiful as it ever has been.

Hull's packstring is a classic picture. The rack of a five-point bull elk sticks up from the mule at the back of the string. Hull says there's a lot of game. The fire hasn't affected hunting back here.

Just below the Middle Fork Lodge, fly anglers try their luck on cutthroats. It's the old Middle Fork.

The fires are still smoldering upstream but Jeff proves life goes on along the Middle Fork.

It's 4:45 p.m. and we're just getting to Upper Jackass campsite. The temperature has dropped to 56 degrees as the sun hides behind a mountain ridge. I remember Upper Jackass campsite from the early ‘90s. It's the same and that is reassuring. What a great campsite.

The tent's up and it's time to relax with a Guinness. Just sipping a brew and watching the river go by. Life is simple on the Middle Fork.

Day Two Oct. 3. 7:30 a.m.

I am not going to get out of this sleeping bag. I never dreamed it would be this cold on the Middle Fork in October.

We're only at about 4,000 feet in elevation, but still, it's so cold. I crawl back into the sleeping bag and wait until someone else gets up to put on the coffee.

Squirrels are chattering. Suddenly I hear the hiss of the gas stove. Good, coffee's brewing.

I peek out the tent flap. A faint light is illuminating the eastern sky. The ridgelines are still dark. Darn October sun, it won't be up for hours, especially with these tall canyons. Heck, might as well get up and do some yoga to loosen up for another full day of kayaking. Yoga feels better on the river. What a place to meditate.

I pile on the poly pro long johns, fleece jacket, wool hat and gloves and fleece pants. It's almost tolerable to get out the the tent.

Shoot man, there's frost on my life jacket. Yeah, FROST!.

You mean I've got to crawl in my wet, frozen neoprene shorts and dry top? My wool socks are frozen solid like boards.

Here I thought I was getting this plush assignment from the Statesman to float the Middle Fork of the Salmon. It has already turned into a survival mission. Got to get to the gas stove and brew some espresso.

We eat breakfast quickly and in no time it's one the river. The heck with the frost. No matter how cold it is, it's time to launch and keep going. Remember, the mission. Remember our Middle Fork.

Despite frozen socks and river shoes, it is turning out to be a good day on the river. We are trying to get to Hospital Bar, a campsite with a hot springs. Hot springs. Soothing hot springs. What a thing to look forward to.

We push downriver. Lower Jackass Flat, Pine Flat, Whitey Cox Hot Springs, Shelf Camp and Loon Creek. They all remain as they have for years and years. There is no recent fire damage. But the fire at Indian Creek and Pistol Creek have us looking more closely at the mountain ridges. Fire has always been a part of the Middle Fork. There is evidence of past fires, but you don't really notice it unless you are really looking for it.

Vegetation grows back, even though it takes decades. It makes you appreciate fire in the wilderness and the renewal that comes.

Hospital Bar Hot Springs

Big Loon Camp, Cow Creek Camp, and Cave Camp. It all looks good. The hours pass quickly and we are pulling into Hospital Bar. Boy, it's good to see Hospital Bar. I love this campsite. It's huge. Large pines are scattered throughout the area. The hot springs is steaming and just the right temperature. There are a few burned trees that have fallen to the ground. A fire came through last summer but the grass came back. The ridge and plateau above the camp burned but it doesn't look like anything had happened. . A year later, the area has been reborn. I pitch my tent next to a huge downed ponderosa pine and settle down with a Guinness. It is black. Several other trees are down in the campsite but the campground on the whole looks just like I remember it years ago. It's a time to remember the trips on the Middle Fork. Hospital Bar is beat to hell. Not from fires but from constant use by river campers. Its grass is trampled. The river bar has been a popular place ever since it was used by the U.S. Army in the 1800s. The Middle Fork has a long history.

The hot springs feels good after a six hours of paddling and rock dodging on the Middle Fork. The water is about 100 to 102 degrees (about the same as my hot tub back home). It's nature's remedy for sore muscles. I just stare at the massive black sky. The hot water soothes the muscles and the black sky soothes the soul. Stars go from one horizon to the other. The world looks minute when you look at a night sky. Life goes on along the Middle Fork.

Day Three Oct. 4 8 a.m.

There's frost on the dry boxes on the rafts this morning. The temperature had dropped into the 30s again. We cook up some sausage and eggs for breakfast. I manage to climb the bluff and find a good place to face east and greet the sun with yoga. Espresso is next.

What would the soldiers who passed through here in the late 1800s think about yoga and espresso. Ah, well.

We finally hit the river at about 11 a.m. We waited for the sun to hit the river but the canyon walls are steep. It's still cold and you can see your breath. My life vest is still frozen.

The first splash of the day is hard to take. But it doesn't matter. I'm glad to see the Middle Fork is the same old Middle Fork. No fire damage for miles as we pass Horsetail Camp, Cub Creek Camp, Upper Grouse Creek Camp and Lower Grouse Creek Camp. I remember having lunch at Upper Grouse Creek a few years back. It was a wonderful time.

My gut gets a little jumpy as we near dreaded Tappan Falls. What the heck is it going to look like?

Tappen Falls at Low Water

It's River Mile 57.9 and there it is. What a mess. At this flow it's nothing but a four-foot drop over a cliff. I can't do it in the kayak.

We all stop to scout. The raft guides look at it and try to find a route on the right side. It's narrow but they can do it. They will hit rocks but the rafts should slide over. They do.

Now it's my turn. I yell downstream that I'm not going to run the main drop. It would take my kayak and flush it as if I was swirling in a toilet. There's also a good chance I can get stuck in the churning mess and pushed up against the bottom of the falls. I don't want to spent that much time in the water, especially on a cool fall day.

I push off and take my kayak down a little slot on the left side of the falls. I can't see the drop until I get around some rocks and take the chute. ROCK. The chute is blocked by a rock and I start back paddling. There's no way through!

I eddy out and get out of my kayak, walking the rest of the way downstream. Sometimes you walk. It's better than a swim.

We Hit the Fire Zone

We stop at Camas Creek Camp for lunch and start to notice some murky water. It's erosion from the fire damage up Camas Creek.

It's getting late in the day and we have to make time if we will get to the Flying B Ranch and talk to the staff and take pictures. That is the crucial part of the trip.

The landscape still looks good. Then, below Funston Camp, we see black here and there and it gets worse. As soon as we round the bend in Aparejo Point Rapids we hit the fire zone. Slopes are blackened but some of the pines are still green. As we push downriver more and more fire damage is evident. Trail Camp's pines are still green and blowing in the wind but the mountain above it is black.

My biggest shock came when we saw Sheep Camp. Oh how I remember the volleyball games at this campsite. The pines along the river bank are blackened part way up the trunks. Hopefully they will live. The giant grassy bowl behind the campsite is nuked. There is still live vegetation in the creek bed. I remember the green, wide open hillsides above Sheep Camp. Sheep Camp is still useable. It will probably green up by next spring. I can't believe that the fire went all the way from the river to the tops of the tree-lined mountain ridges. It looks about seven miles away. We walk Sheep Camp and ponder what the blaze looked like. It's hard to imagine being back here. It's time to shove off and see what we were all anticipating - the Flying B Ranch. The B as it is affectionately known. It's just around the bend. The river takes us around the bend and there is the shoreline of Mormon Ranch. Black. The vegetation fried to a crisp. The ranch, which is located on the east side of the river is OK but the mountainsides and canyons were singed. It's the same story for the hillsides on the west side of the river. Black. I'm really getting tired of black. It's heartbreaking, although you know it's nature's way.

The Flying B Ranch

It's late afternoon and we approach The B. It was the place of the stories of a fire hurricane. A fire ball ripped down the canyon and day became night. The stories that flowed across the Internet were riveting.

I was well ahead of the group as my kayak hit the riffle just above the beach at The B.

It looks bad. The vegetation along the shoreline was nuked. I had to see The B. Was the lodge still there?

I walk up the trail with an ache in my gut. There it is. The familiar brown log lodge is just the way it had been all the years I've visited it. I remember spending hours here waiting for a plane to take me out of the backcountry after a cutthroat trout fishing trip.

The lawn in front of the place is still green. The weathered deer and elk antlers are still there. What I notice immediately is that the canyon above the lodge looks like it was hit by napalm. The hillsides have no vegetation.

Brush Creek is nuked. I can't use another word to describe it. The black carcass of a coyote remains in the creek bed where the animal had sought shelter from the firestorm. The animal was flash-dried in a state like hardened molten lava. The coyote apparently had crouched down to let the fire go over it. The fire didn't. and the animal now looks like something out of Pompei. It was bad. The staff at the Flying B show us around. They lost 90 tons of hay, one cabin and the roof off another building. How they saved the place is beyond believe. They have photos of the remains of dead bear, deer and grouse. They were flash frozen in time by an intense blaze.

Fire Buckles a Bridge

A walk down to the river reveals the fury of the firestorm. The packbridge at The B was blown off its foundation by the windstorm in front of the fire. The bridge is buckled in one spot and it suddenly dawns on you. The magnitude of the hurricane force winds that precede a fire.

The Flying B was at the eye of the fire hurricane but it has survived. "It was a war zone," George Fattig said, "I thought I was dead." Fattig is one of the workers at the ranch.

River runners who come down the Middle Fork next season will be able to stop in for ice cream or souvenior t-shirts. They will be able to sit on the green lawn and take a break.

They'll find the lodge intact. Inside are the varnished log walls and a stone fireplace. Across the main room is a player piano with a stuffed cougar sitting on it. Elk, antelope and deer heads adorn the walls. Yes, the famous B is still there.

Day Four - Oct. 4 7:30 a.m.

Darn squirrel. I want to sleep in. Shoot!

Shut up! I'm a wreck from yesterday's long day. Goll, my bones are sore and

my muscles feel like they're been stomped by a mule.

We pack up so fast that my kayak still has ice in it. Another day of putting on frozen kayak clothing. The things I do for the Statesman. As we get ready to shove off, my heart sinks. There it is. A black sludge curls around the rocks and shoreline. I put my white paddle in the river and it becomes wrapped in what looks like an oil slick. Well, there wasn't an oil spill on the river. It was the ash, silt and speckles of granite. The river is running gray from the silt coming down Brush Creek at the Flying B. Remember, Brush Creek's vegetation was totally nuked. There is nothing to hold back the silt and mud. It is now making its way down the Middle Fork. The river is cloudy. We meet up with a Forest Service trail crew at Driftwood Camp. They are fixing the trail from Camas Creek to the mouth of Big Creek. All their equipment is on a pack string. As we shove off after talking with them, I notice a scum of ash that has settled on the beaches in the area. It is like a black bath tub ring. It will probably get cleaned out by high water next spring but you never know. Brush Creek wasn't going to become stable until new vegetation takes over the creek bed. There was more fire damage in this area. Wilson Creek Camp is burned to the beach. The underbrush is gone, but luckily, the big ponderosa pines remain. One is black 20 feet up its trunk. Downriver, Grassy Flat Camps 1 and 2 are black. But already, Oregon grape shoots are poking through the blackened ground. The grassy camps will be green again by spring. We stop at Rattlesnake Creek and Rattlesnake Cave to look at the pictographs. The area is intact and has been spared by the fire. The historical evidence of past peoples survived for the future. I love the pictograph of a caribou with hunters. We head downriver. Survey Creek Camp, partially burned. We blast through Waterfall Rapids. It was bony. I barely made it over a couple of boulders.

Waterfall Creek Untouched by Fires

I had to see Waterfall Creek. It's so beautiful. Did the fire get it? Luckily, no.

Waterfall Creek gushes its velvety flow as usual. Thank the river gods it was untouched.

We stop at Big Creek for lunch. I remember a pack trip down Big Creek in the early ‘80s. We camped about 7 miles down from the trailhead and the canyon was thick with green pines and underbrush. I put on a grasshopper fly and crawled through the brush dropping it in swirling pools. Cutthroats would hammer it. Half the time a cutt would take it make a run over a log and break off. Those cutts were big.

Wonder what it looks like where I fished? The mouth of the Big Creek was not touched by fire.

The scene downriver looks like the old Middle Fork. No fire damage. But if you look up Big Creek, you can see where fire burned the ridgelines. A brackish water flowed down Big Creek into the Middle Fork. It's a sign of runoff to come.

The dark water is a sure sign that something had gone on upstream on Big Creek. You could see it.

We float along in gentle waters. Suddenly, I look up and there it is. Veil Falls. The falls is a favorite among floaters. It's a landmark. It's on a high cliff overlooking the river. The whole rock cliff looks like a giant amphitheater. It, too, was untouched by fire. Lots a times in past trips we would hike up to the falls and stand under its mist. Not today, we had to make time. I'm glad Veil Falls is as beautiful as ever.

Time flies and Porcupine Rapids appears on the horizon. Here we go. Watch the big rock ledge. Yikes, look at it. Paddle. Paddle. Paddle. Whew! Jeez, that rock wall is coming up too fast, where the heck do I go? A cushion of water pushes me somewhere and within seconds I'm in quiet water watching two rafts splash through. It's non-stop. In less than two miles we approach the head of Redside Rapids. It's a short, steep drop with huge boulders. I go for it. Success by the skin of my teeth again. It's not a place to relax. In about three-tenths of a mile Weber Rapids greets us. My forearms are aching. Workman's comp? I was getting cold because of being doused with icy water in waves and holes. My kayak had hit so many rocks, I didn't think it had much life left. My backup paddle is taking a beating on the rocks. Weber scares the heck out of me. It's one of the meanest rapids on the river. It's a rocky mess. All I did was slip over boulders and fall into big holes. Blip. Bam. Blip. Bam. It's like taking punches from a heavyweight champion. Weber is a heavyweight. I find myself in quiet water again, wondering what the heck had happened. I'm still upright. Good sign. The Forest Service guys still think I'm a good boater. Ha! We float another couple of miles and come up on Parrot Cabin. Did it burn? An old Middle Fork character Earl Parrott mined this stretch of river. He was a hermit and had an elaborate ladder system going from his river cabin to another cabin up in a mountain valley 2,000 feet above the river. The river cabin was there - another historical site that was not touched by fire.

We couldn't stay long at Parrot Cabin. Had to blast downstream. It's getting late in the day and we want to make Cliffside Camp, which is about two miles away.

It's late, around 5:30 p.m. and we are at Cliffside camp setting up tents and getting the cooking area ready. A can of Guinness sounds good at this point as I write in my journal and record a packed day of events. As daylight disappears, moonlight starts to brighten, casting shadows on the cliff opposite the camp. It's beautiful. What a place to be.

Day five, Oct. 6, 8 a.m.

I'm awakened by the clank of dishes. Someone's brewing coffee. It's 37 degrees in the tent. Got to be well below freezing outside.

I crawl out of my sleeping bag and put on fleece from head to toe. Wool gloves. Wool hat. It's time to peek out of the tent. This morning I'm greeted by a pair of ouzels as I go through my yoga routine on the beach. Great place for yoga.

They are so limber as they dance from rock to rock. Ouzels have such a cheery spirit. They are truly a whitewater bird. Love they way they dive, dip and bounce all over the place.

Life goes on along the Middle Fork.

Back to yoga. Got to loosen up or this 53-year-old paddler will pull some muscles he never knew existed.

We've got to blast out of here and it's too cold to get on the river. There's a puddle of ice in my kayak. I can't get it out. I'll just have to sit in it. Cold butt.

I finally see some tracks around my tent. Bighorn tracks. Can't believe they came into camp.

Enough of the wildlife lesson.

The first splash comes in Ouzel Rapids. I didn't need it right in the face. Ouzels are following me down river. That's good. They are good luck.

"Are we going to stop and scout Rubber Rapids," I yelled to Ken. No, we're just going to blast through, he says.

It's a Class IV rapids and known for flipping rafts and kayaks. You can hear it around the bend. Norm's raft goes through bouncing over rocks. I follow close behind getting bounced over rocks and launched into holes. I'm not awake yet and almost go over. "That was wild," I yell.

"That's not Rubber," Norm yells back. It was a no name rapids above Rubber. I'm in deep, deep trouble.

Rubber comes fast. The horizon line looks foreboding. This is it. Rubber is one of the biggest rapids on the river. Did I say that already.

We all slip through it with ease and without thinking. Rubber is a puppy at low water. The rapids above it were more difficult.

This is the last day on the river. We are hoofing it to get to the take out on the Main Salmon at Cache Bar.

There no stopping for Hancock Rapids. It's another rocky mess that has rafts scraping over rocks and me getting banged and bounced like a pool ball.

Devils Tooth drops me, spins me and shoots me downstream. House Rock and Jump Off rapids try to flip me.

After all that I'm still upright.

We near the confluence of the Middle Fork and the Main Salmon. Civilization. There's a car. A truck. Steelhead anglers line the banks of the Main.

We have completed five days on the Middle Fork.

Yes, parts of it had burned. Parts of it will burn in future years.

No matter what: Life goes on along the Middle Fork and I want to be part of that life.

Related Links

For more information about the Salmon River country, check out these related sites.

National Wilderness Preservation System

Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness

Payette National Forest

Information on the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness

Your Guide to Outdoor Recreation and Active Travel

Destinations - Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness

City of Salmon

Official website of the largest town along the Salmon River

Salmon-Challis National Forest

Where to go to get a river permit for the Main and Middle Fork Salmon

Idaho Outfitters and Guides Association

More than 400 outfitter/guides and related services

Idaho Whitewater Association

An up-to-date site for private boaters