IdahoPTV Specials

Please note that this content is no longer being updated. As a result, you may encounter broken links or information that may not be up-to-date. For more information contact us.

Assassination: Idaho's Trial of the Century

At the dawn of the twentieth century, the fierce passions of class warfare crackled through the mining camps of Colorado, Idaho, Utah and Montana.

This social and economic whirlwind eventually felled one of Idaho's favorite sons, former Governor Frank Steunenberg.

The ensuing trial thrust Idaho into the spotlight, as two of the West's sharpest lawyers, James Hawley and William Borah, clashed with the legendary Clarence Darrow in a "struggle for the soul of America."

Famous attorneys James Hawley and William Borah presented their case in a Boise courtroom in 1907.

The Trial

In the summer of 1907, a battle between workers and capitalists, that had been developing for decades, finally played out in a Boise, Idaho, courtroom.

William D. "Big Bill" Haywood stood charged with hiring hitman Harry Orchard to assassinate former Idaho governor Frank Steunenberg on December 30, 1905. Haywood was the secretary-treasurer of the Western Federation of Miners, a union with a reputation for violence. Although the union leader was not even in Idaho when Steunenberg was dynamited, Idaho's Governor Gooding was convinced the labor union was behind the murder.

The ensuing trial, which lasted from May 9th until July 28th, was one of the most significant events in the history of Idaho. It was also one of the most famous criminal trials in the history of our country.

Through the reporting of more than fifty national and international journalists, the world followed this courtroom confrontation of the working class and the capitalists day by day. Orchestrating the drama were some of the legal giants of the era, including: James Hawley, reputedly the best criminal lawyer in the West; William Borah, newly elected United States Senator from Idaho; and Clarence Darrow, the legendary "attorney for the damned."

The Not Guilty verdict surprised everyone, even Darrow. There are those who think justice was not served, that the judge's instructions to the jury regarding corroborating evidence made a confession virtually impossible. But others point to this trial as one of the best examples in American jurisprudence of justice under the law.

Key Players

Frank Steunenberg came to Idaho from Iowa in 1886, settling in Caldwell, where he was involved in publishing a newspaper with his brother. He served as a delegate to the state constitutional convention in 1889 and was a member of the Idaho House of Representatives in the first state legislature from 1890 to 1893. In 1896, he was elected Idaho's fourth governor, was re-elected in 1898 for another two-year term. He was a Democrat, who gained the top office in state government with Silver Republican, Populist, and labor support.

In 1899, striking miners in the Coeur d'Alene mining district of north Idaho blew up the Bunker Hill and Sullivan Mine concentrator, and there was virtual armed warfare in the mining community. Governor Steunenberg declared martial law. Because the Idaho National Guard was in the Philippines, because of the Spanish-American War, Steunenberg called on President McKinley to send in federal troops to reestablish law and order.

The federal troops arrested a large number of the striking miners and herded them into "bull pens," which were lacking in proper sanitation, poorly equipped, and caused the miners to become very agitated. The Western Federation of Miners, a union that represented the striking miners, blamed Steunenberg directly for this humiliation and for the harm to their members.

On the evening of December 30, 1905, Steunenberg was assassinated by a bomb placed at the gate to his residence in Caldwell.

Albert E. Horsley, alias Tom Hogan, alias Harry Orchard

Within a few hours of Steunenberg's death, suspicion began to focus on a man who had been in Caldwell only a few weeks, and whose only apparent reason for being there was his self-proclaimed business as a sheep buyer. Yet, there was no appearance that he had purchased any sheep during his stay. He was registered at the Saratoga Hotel as "Tom Hogan," but during the investigation that followed the assassination, he was recognized as a man named "Harry Orchard" who had been a miner in north Idaho in 1899.

Using a pass key obtained from the hotel, a friend of Steunenberg searched Hogan's room and found evidence of what appeared to be the makings of a bomb similar to the one that killed the former governor. Fragments of plaster of Paris like the foundation of the bomb and fish line identical to the trip string attached to Steunenberg's gate, seemed clearly to implicate Hogan, or Orchard as he became known, and he was arrested.

Eventually, James McParland of the Pinkerton Detective Agency, which had been brought into the case by the State of Idaho, secured a confession from Orchard, that Orchard had set the bomb that killed Steunenberg and that the "inner circle" of officials of the Western Federation of Miners had hired him to kill the former governor.

Orchard also admitted he had killed at least seventeen others besides Steunenberg in support of the activities of the Western Federation of Miners in Colorado and Idaho.

Orchard also admitted that his true name was Albert E. Horsley, that he had come to the United States from Ontario, Canada in 1896, and that he had left a wife and daughter in Canada. During his incarceration, he converted to the Seventh-Day Adventist faith, after Steunenberg's widow, Belle, publicly forgave him for murdering her husband.

In 1907, Orchard testified against William D. "Big Bill" Haywood, the secretary-treasurer of the Western Federation of Miners in a trial in Boise.

In 1908, Orchard testified against George Pettibone, an adviser to the Western Federation. Both Haywood and Pettibone were acquitted of the charges against them for allegedly hiring Orchard to kill Steunenberg.

In 1908, Orchard pled guilty to murdering Steunenberg, and was sentenced to be hanged, but the Idaho Commission on Pardons and Parole commuted the sentence to life in prison.

Orchard served forty-six years in the Idaho State Penitentiary, dying in 1954, after having survived all the others who were participants in the Haywood trial.

William D. "Big Bill" Haywood was secretary-treasurer of the Western Federation of Miners, in the early 1900's and one of the founding members of the most aggressively violent union in the United States, the Industrial Workers of the World, the I.W.W., or the "Wobblies," as some people called them.

After Harry Orchard implicated him and the other members of the "inner circle" of the Western Federation of Miners, Haywood was kidnapped from Colorado to Idaho and stood trial in 1907 for hiring Orchard to kill Steunenberg.

Haywood was acquitted, left the Western Federation, and became president of the I.W.W.

During World War I, Haywood was convicted of sedition for opposing the war. While he was on bail awaiting his appeal, he fled to Russia, where he died a few years later. Part of his ashes are in the Kremlin, the rest in Chicago.

McParland was the most famous of the Pinkerton detectives and was enlisted by Governor Gooding to interrogate Orchard. McParland had been the one who broke up the miners' union in Pennsylvania known as the "Molly Maguires" in the 1870's.

At McParland's direction, Orchard was taken from the local jail to the Idaho State Penitentiary in Boise, where he was placed in solitary confinement for ten days before McParland commenced his interrogation. During his first session with Orchard, McParland made it clear to Orchard that the state had sufficient evidence to convict and hang Orchard without any confession from him.

McParland did, however, tell Orchard that if Orchard would implicate the Western Federation of Miners, McParland would see that Orchard didn't hang. McParland said he knew already that Orchard had been employed by the "Inner Circle" of the union to kill Steunenberg, although McParland at that time had no evidence to support this theory.

At the second session with McParland, Orchard probed McParland to establish McParland's ability to save Orchard's life. Then, Orchard, not so surprisingly, "confessed" to killing Steunenberg and said he had been hired to do so by officials of the Western Federation of Miners, specifically Haywood, as well as the union president, Charles Moyer, an advisor to the union, George Pettibone, and another union operative, Jack Simpkins.

James Hawley, who by many observers was considered to be the best criminal lawyer in the West, had come to prospect for gold in the Boise Basin, northeast of Boise, as a teen-ager in the early 1860's, was appointed as a special prosecutor to prosecute Haywood, Moyer, and Pettibone. He had become co-owner of a rich silver claim, which he and his partner sold in the mid-1860's.

With his substantial profits, Hawley went to San Francisco, where he studied in college for two years. After a sojourn as a seaman and adventurer in the Far East, Hawley returned to Idaho, where he served in the territorial legislature, then studied law, became a lawyer, federal prosecutor, and a very successful defense lawyer. It is said he was involved in 300 murder cases during his career.

In 1910, he was elected governor of Idaho on the Democratic ticket and served two years.

In 1927, he spoke at the dedication of a statue of Steunenberg in front of the Statehouse in Boise. It is said he was the one who convinced those in charge of placing the statue to have Steunenberg face the Statehouse, instead of looking south on Capitol Boulevard. It is said the reason for this was so that the elected officials in the Statehouse would know that the former governor was keeping his eye on how they were governing the state.

William E. Borah came to Idaho as a young lawyer in 1890. He quickly became prominent both as a lawyer and politician in the Republican Party. Borah was a friend and political colleague of Steunenberg, even though they were members of different political parties. He delivered the eulogy at Steunenberg's funeral.

In early 1907, Borah was elected by the Idaho legislature to be the new U.S. Senator from Idaho. This was before the Seventeenth Amendment, and just a few months before the Haywood trial began. Borah delayed taking his seat in the Senate so he could help try the Haywood case.

It is noteworthy that Borah opposed trying the officials of the Western Federation of Miners in Idaho, preferring to try only Orchard, and leaving the prosecution of the union officials to Colorado. But, other Idaho officials felt differently and prevailed.

A complicating factor for Borah was that during the pendancy of the Haywood case before trial, he was charged in federal court with timber fraud, based on his being the general counsel for the Barber Lumber Company, which had allegedly acquired timber claims in violation of federal law. Coincidentally, Steunenberg was one of the principals of the Barber Lumber Company. Through the intervention of President Teddy Roosevelt, Borah's trial was postponed until after the Haywood trial. Borah was tried shortly after Haywood was acquitted in 1907. He was defended by Hawley and was himself quickly acquitted.

After he took his seat in the U.S. Senate, Borah quickly became a respected member of that body. From 1924 to 1933 he was chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. In 1936, Borah, "the Lion of Idaho," was an early contender for the Republican nomination for the presidency of the United States, but did not get the nomination.

Darrow was one of the two leading defense attorneys who represented Haywood, Moyer, and Pettibone. He began his legal career in Ohio, then moved to Chicago where he became a lawyer for the city. He moved on to represent the railroad. At the time of the Pullman Strike in 1894, he asked management of the railroad that he not be required to oppose the striking railroad workers. He was released from doing so, and represented Eugene Debs, the President of the American Railway Union. In 1904, he helped the anthracite coal workers in Pennsylvania during the federal arbitration that resolved their strike.

In 1906, he was hired to assist in the defense. Even some of his fellow defense attorneys called him "Old Necessity," after the legal adage: "Necessity knows no law." But, Darrow did know human nature and was a past master of winning juries over to his client's side of the case, as he did in both Haywood and Pettibone's cases.

More importantly, Darrow defused the prosecution's case against Haywood by convincing the prosecution's key witness for corroboration of Orchard's testimony implicating the "inner circle" of the Western Federation of Miners to renounce his confession. This prevented the state from calling this witness, Steve Adams, to testify against Haywood and Pettibone, when they were tried.

Edmund Richardson, the other lead defense attorney, was general counsel for the Western Federation of Miners. He was a very experienced and capable lawyer, but he and Darrow had different approaches to the case, and they quickly became at odds, although they both continued to share space at the defense table during the two and one-half months of trial.

He cross-examined Orchard for twenty-six hours over five days, without gaining any concessions from Orchard that would weaken his incrimination of Haywood and the other officials of the Western Federation of Miners.

Judge Fremont Wood

Judge Fremont Wood had been the U.S. Attorney in Idaho in 1892 who prosecuted the striking miners in the Coeur díAlenes for criminal conspiracy that year. He was a district judge from Ada County and was assigned to the case because the district judge in Canyon County had a conflict of interest. Wood transferred the venue of the case to Ada County for better security and to accommodate jury selection.

His concern to not let his own prejudices in the case influence the jury might have led him to deliver instructions to the jury that left them little choice but to acquit Haywood.

Charles Moyer

He was president of the Western Federation of Miners in the early 1900's. Orchard implicated him in the assassination of former governor Steunenberg. He was also kidnapped from Colorado to Idaho and awaited trial in jail in Boise.

After Haywood and Pettibone were tried and acquitted, the prosecution dismissed the case against Moyer.

George Pettibone

He was an adviser to the officers of the Western Federation of Miners in the early 1900's. He was famous for developing a high powered bomb called variously "Pettibone Dope," "Greek Fire," or "Hellfire," which was similar to the bomb with which Orchard killed Steunenberg. He was kidnapped from Colorado to Idaho in 1906. In 1908 Pettibone was tried and acquitted for hiring Orchard to kill Steunenberg.

Jack Simpkins

He was the fourth member of the "inner circle" of officials of the Western Federation of Miners whom Orchard said hired him to assassinate Steunenberg. Simpkins was in charge of the operations of the Western Federation of Miners in Idaho. In 1905, he accompanied Orchard to Caldwell and was there with him until at least November.

Although the State of Idaho and the lawyers defending Haywood, Moyer, and Pettibone tried to find Simpkins, no one was successful in doing so. He simply disappeared, and no one has found him since, even up to the present day.

He may well have been the key to resolving whether Orchard was hired to kill Stunenberg, and, if so, by whom.

Governor Frank Gooding

Governor Gooding was the governor of Idaho when Stuenenberg was assassinated. He was very much involved in bringing the Pinkerton Detective Agency into the case.

Closing Arguments

We have for ten weeks, gentlemen of the jury, been in continuous session in this court, giving our attention to this question. It is probably the most important criminal case that was ever given to a jury for its attention and consideration in these United States . . . .

We are not here to urge the conviction, gentlemen, of a man whom you believe is innocent or think under any circumstances can be innocent. We are not here, gentlemen, representing anyone except the state of Idaho.

We have been engaged here in making history, I might say; this case will be looked upon as one of the most important in the criminal annals of the country. It is important, therefore, that we do our duty fully and come to a correct conclusion.

The days pass and the Christmas season comes with all its thoughts — of peace and good will — the season when men live with their families, when people of the Christian faith rejoice, and if there is ever a time when all thought of fear should be laid aside then is the time. That is the season when love for mankind should rule, and exist if at all. That is the season when men should most feel safe from harm.

Just as the old year was fading — just as the new year was about to make its appearance — when all seems safe and peaceful, Orchard lays his bomb in front of Steunenberg's gate, and that night as the governor hastens home through the dusk to his family, in his mind the happy thoughts of the loving greeting in store for him . . . he is sent to face his God with out a moment's warning and within the sight of his wife and children. . . .

Now, I am not one of those that believe in death bed conversions . . .

Gentlemen, the conviction has been forced upon me in this case, as I believe it has been forced upon every man that heard the testimony of Harry Orchard, that some cause has impelled him to tell the entire truth. I think I understand what that cause is. I believe it is the religious training of his early youth awakened by those references that were made to him in the loneliness of his cell by the gentleman who approached him and obtained his confession . . .

And I believe that we are warranted in coming to the conclusion that it was the saving power of divine grace, gentlemen of the jury, working upon the conscience of this man that finally impelled him to make this confession that in all probability will bring to the bar of justice the worst set of conspirators that have ever infested any section of the United States.

I'll tell you this, gentlemen: If Orchard had killed anybody else besides Steunenberg or some man who had not acted contrary to the interests of the Western Federation of Miners — had not gained their enmity — you wouldn't have found Moyer and Haywood putting up any $1,500 or 15 cents for his defense. That money was not to defend Orchard. It was not put up to protect him so much as it was put up to protect their own necks. . . . .

Gentlemen, it is time that this stench in the nostrils of all decent persons in the West is buried. It is time to forever put an end to this high handed method of wholesale crime. It is the time when Idaho should show the world that within her borders no crime can be committed and that those who come within her borders must observe the law.

Gentlemen, I wish that I could look over this evidence and find some way of satisfying myself that this man here upon trial was innocent and that these other men associated with him in this indictment were also innocent of this offense. I have no desire, gentlemen, to have the scalp of any innocent man hanging at my girdle . . .

But we can come to but one conclusion, and that is that he is not only responsible for this atrocious murder but that for more than a score of other murders that have been proven here he is equally responsible.

I ask you to take this evidence and carefully consider it. I ask you to give it that weight and consideration that under the instructions of the court it will be entitled to. I ask you that you honestly, in your own good judgment, apply the law to the evidence and thus find your verdict. And I for one, gentlemen, will say in advance that with the utmost confidence in this jury and every member of it, I will be satisfied whatever that verdict may be. Gentlemen, I thank you for your attention . . . .

It had been Governor Steunenberg's fortune while governor of this state to be called upon to stand in the forefront of a labor controversy which occurred in the northern part of the state. Perhaps the situation demanded of him all that he did. I don't know about that, and I am not going to discuss it . . . .

One thing is certain, that it gave rise to an endless amount of discussion throughout the entire civilized world. For the first time in the history of America the military bull pen was established in the administration of what were practically civil affairs. For the first time in the history of America men were deprived of their liberty with, perhaps, just cause but without due or any process of law.

They arrested the union miners right and left without warrant. They deprived them of their liberties. They threw them in the dirty, vile-kept bullpens and they were subjected to all sorts of indignities and insults at the hands of those negro soldiers.

If you had been there, covered with vermin . . . if you'd been there, gentlemen of the jury, it is certain that you would have attained in your breast a righteous hatred for every person who had anything to do with causing your humiliation and suffering . . . .

Where is this ‘terror to evildoers,' as Mr. Hawley has called him. Hawley promised you he would have Mr. McParland tell his story. Never but once has his figure darkened the door of this courtroom . . . Was he afraid of the questions I would ask him on cross examination? Where are the other slimy Pinkertons who sneaked in our unions to make trouble? Why have they not testified?

I say this man [Orchard] is a cheap and a tawdry and a tinsel hero, seated on this witness stand like a king upon his throne...under a promise as plain as noonday that his worthless head and carcass shall be saved if only there can be secured a condemnation of the officers of the Western Federation of Miners. Which would you rather believe, this man on the stand wearing his cheap bravado and putting obloquy upon those who are innocent, or this husband and this father [pointing to Haywood], an exemplary citizen all of his life, nursing tenderly and caring properly for this crippled woman who now sits and has for long year sat by his side?

Gentlemen, I sometimes think I am dreaming in this case. I sometimes wonder whether this is a case, whether here in Idaho or anywhere in the country, broad and free, a man can be placed on trial and lawyers seriously ask to take away the life of a human being upon the testimony of Harry Orchard. We have the lawyers come here and ask you upon the word of that sort of a man to send this man to the gallows; to make his wife a widow, and his children orphans — on his word. For God's sake what sort of an honesty exists up here in the state of Idaho that sane men should ask it? Need I come here from Chicago to defend the honor of your state? A juror who would take away the life of a human being upon testimony like that would place a stain upon the state of their birth and their nativity — a stain which all the waters of the great seas could never wash away, and yet they ask it. You had better let a thousand men go unwhipped of justice — you had better let all the criminals that come to Idaho escape scot free than to have it said that twelve men of Idaho would take away the life of a human being upon testimony like that.

There are certain qualities which are primal with religion. I undertake to say, gentlemen, that if Harry Orchard has religion now that I hope I may never get it. I want to say to this jury that before Harry Orchard got religion he was bad enough, but it remained to religion to make him totally depraved . . . .

I see what to me is the crowning act of infamy in Harry Orchard's life, an act which throws into darkness every other deed that he ever committed as long as he has lived, and he didn't do this until he had got Christianity or McParlandism, whatever that is ; until he had confessed and been forgiven by Father McParland he had some spark of manhood still in his breast.

I don't believe that this man was ever loyally in the employ of anybody. I don't believe he ever had any allegiance to the Mine Owners' Association, to the Pinkertons, to the Western Federation of Miners, to his family, to his kindred, to his God, or to anything human or divine. I don't believe he bears any relation to anything that a mysterious and inscrutable Providence has ever created... . He was a soldier of fortune ready to pick up a penny or a dollar or any other sum in any way that was easy . . . to serve the mine owners, to serve the Western Federation, to serve the devil if he got his price, and his price was cheap.

For thirty years I have been working to the best of my ability in the cause in which these men have given their toil and risked their lives; for thirty years I have given the best ability that the God has given me; I have given my time, my reputation, my chances, all this to the cause which is the cause of the poor. I may have been unwise, — I may have been extravagant in my statements, but this cause has been the strongest devotion of my life, and I want to say to you that never in my life did I feel about a case as I feel about this; never in my life did I wish anything as I wish the verdict of this jury, and if I live to be a hundred years old, never again in my life will I feel that I am pleading a case like this . . .

Other men have died in the same cause in which Bill Haywood has risked his life. Men strong with devotion, men who love liberty, men who love their fellow men have raised their voices in defense of the poor, in defense of justice, have made their good fight and have met death on the scaffold, on the rack, in the flame, and they will meet it again until the world grows old and gray. Bill Haywood is no better than the rest; he can die, if die he needs. He can die if this jury decrees it, but, oh, gentlemen, don't think for a moment that if you hang him you will crucify the labor movement of the world . . .

Let me tell you, gentlemen, if you destroy the labor unions in this country, you destroy liberty when you strike the blow, and you would leave the poor bound and shackled and helpless to do the bidding of the rich.

Gentlemen, it is not for him alone that I speak. I speak for the poor, for the weak, for the weary, for that long line of men who in darkness and despair, have borne the labors of the human race . . . .

The eyes of the world are upon you, upon you twelve men of Idaho tonight . . .

If you should decree Bill Haywood's death, in the great railroad offices of our great cities men will sing your praises. If you decree his death amongst the spiders of Wall Street will go up paeans of praise for these twelve good men and true who killed Bill Haywood. In every bank, almost, in the world, where men hate Haywood because he fights for the poor and against the accursed system upon which the favored live and grow fat, from all those you will receive blessings and praise, that you have killed him.

[But if your verdict should be 'not guilty,'] There are still those who will reverently bow their heads and thank these twelve men for the life and the character they have saved. Out on our broad prairies where men toil with their hands, out on the wide ocean where men are sailing the ships, through our mills and factories, down deep under the earth thousands of men, and of women and children — men who labor, men who suffer, women and children weary with care and toil, — these men and these women and these children will kneel tonight and ask their God to guide your judgment, — these men and these women and these little children, the poor the weak and the suffering of the world, will stretch out their hands to this jury and implore you to save Haywood's life.

There is here no fight on organized labor. This is simply a trial for murder. Frank Steunenberg has been murdered, and we want to know. A crime has been committed, and the integrity and the manhood of Idaho wants to know. An offense which shocked the civilized world has taken place within our borders, and unless we went about it earnestly and determinedly to know, we would be unfit to be called a commonwealth in the sisterhood of commonwealths of the Union.

Watch these five men. In a little over thirty days Frank Steunenberg is going to die. What are their actions? They are going to and fro, their association, their connection — you will find out whether there is evidence here or not to show a conspiracy outside of any testimony of Harry Orchard. . . . Watch them. . . . We have got them in touch with one another. They are moving to the scene.

. . . Why? Why? Always back to Denver? Unless it was to find there the protection and the pay of his employers. . . . (this last sentence is the one Judy is having a hard time tracking down in the actual transcripts, but it's been quoted in books; we'll have to get back to you).

You are carrying with you tonite the solicitude of an entire people.

There is no home in Idaho tonight, but that a thought of you and your final duty will mingle with the sentiment which made that home possible . . .

After the trial has been finished, after the work is over... the thing which will remain with us is that sleepless mentor of the soul asking over and over again as the years go by were you brave and faithful in the discharge of the most solemn duty of your life?

You have no doubt often in this case been moved by the eloquence of counsel for the defense.

They are men of wonderful powers. They have been brought here because of their power to sway the minds of men. . . to sometimes draw you away from the consideration of the real facts in this case, to beguile you from a consideration of your real and only duty. But as I listened to the voice of counsel and felt for a time their great influence, there came to me after the spell was broken another scene. . .

I remembered again the awful thing of December 30, 1905, a night which has added ten years to the life of some who are in this courtroom now.

I felt again its cold and icy chill, faced the drifting snow and peered at last into the darkness for the sacred spot where last lay the body of my dead friend, and saw true, only too true, the stain of his life's blood upon the whitened earth. I saw Idaho dishonored and disgraced. I saw murder — no, not murder, a thousand times worse than murder — I saw anarchy wave its first bloody triumph in Idaho. And as I thought again I said, 'Thou living God, can the talents or the arts of counsel unteach the lessons of that hour?' No, no. Let us be brave, let us be faithful in this supreme test of trial and duty.

Some of you men have stood the test and trial in the protection of the American flag. But you never had a duty imposed upon you which required more intelligence, more manhood, more courage than that which the people of Idaho assign to you this night in the final discharge of your duty.

Newspaper Headlines from the Trial Period

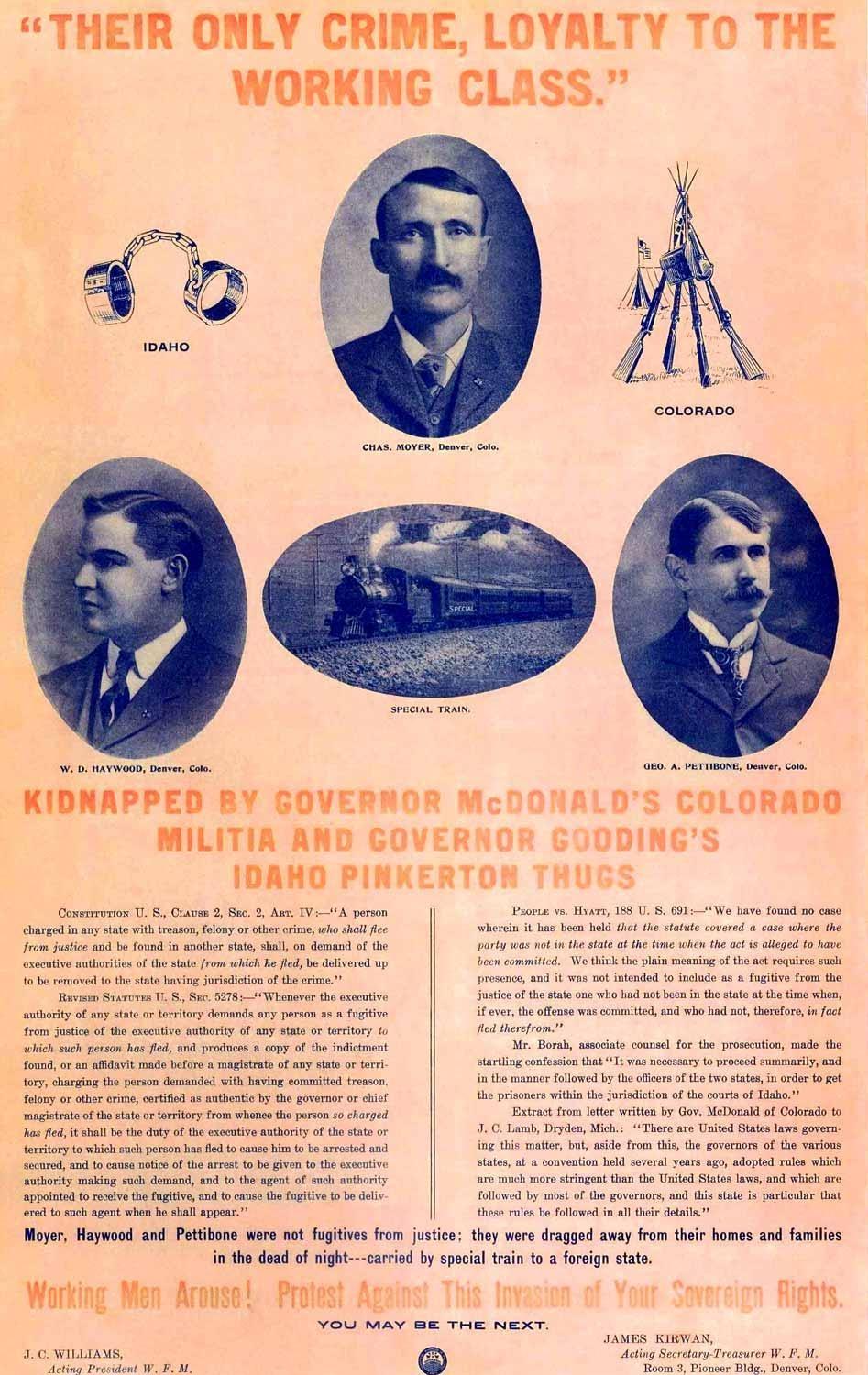

“THEIR ONLY CRIME, LOYALTY TO THE WORKING CLASS.” KIDNAPPED BY GOVERNOR MCDONALD’S COLORADO MILITIA AND GOVERNOR GOODING’S IDAHO PINKERTON THUGS

CONSTITUTION, U.S. CLAUSE 2, SEC. 2, ART. IV: - “A person charged in any state with treason, felony, or other crime, who shall flee from justice and be found in another state, shall, on demand of the executive authorities of the state from which he fled, be delivered up to be removed to the state having jurisdiction of the crime.”

REVISED STATUTES, U.S., SEC. 5278: - “Whenever the executive authority of any state or territory demands any person as a fugitive from justice of the executive authority of any state or territory to which such person has fled, and produces a copy of the indictment found, or an affidavit made before a magistrate of any state or territory, charging the person demanded with having committed treason, felony, or other crime, certified as authentic by the governor or chief magistrate of the state or territory from whence the person so charged has fled, it shall be the duty of the executive authority of the state or territory to which such person has fled to cause him to be arrested and secured, and to cause notice of the arrest to be given to the executive authority making such demand, and to the agent of such authority appointed to receive the fugitive, and to cause the fugitive to be delivered to such agent when he shall appear.”

PEOPLE VS. HYATT, 188 U.S. 691: -- “ We have found no case wherein it has been held that the statute covered a case where the party was not in the state at the time when the act is alleged to have been committed. We think the plain meaning of the act requires such presence, and it was not intended to include as a fugitive from the justice of the state one who had not been in the state at the time when, if ever, the offense was committed, and who had not, therefore, in fact fled therefrom.”

Mr. Borah, associate counsel for the prosecution, made the startling confession that “It was necessary to proceed summarily, and in the manner followed by the officers of the two states, in order to get the prisoners within the jurisdiction of the courts of Idaho.”

Extract from letter written by Gov. McDonald of Colorado to J.C. Lamb, Dryden, Mich.: “There are United States laws governing this matter, but aside from this, the governors of the various states, at a convention held several years ago, adopted rules which are much more stringent than the United States laws, and which are followed by most of the governors, and this state is particular that these rules be followed in all their details.”

Moyer, Haywood, and Pettibone were not fugitives from justice; they were dragged away from their homes and families in the dead of night – carried by a special train to a foreign state.

WORKING MEN AROUSE! PROTEST AGAINST THIS INVASION OF YOUR SOVEREIGN RIGHTS. YOU MAY BE NEXT.

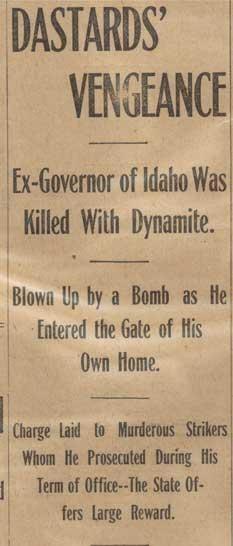

From THE FORT WAYNE JOURNAL-GAZETTE

Front page 12/31/1907

Ex-Governor of Idaho Was Killed With Dynamite Blown Up by a Bomb as He Entered the Gate of His Own Home. Charge Laid to Murderous Strikers Whom He Prosecuted During His Term of Office. The State Offers Large Reward.

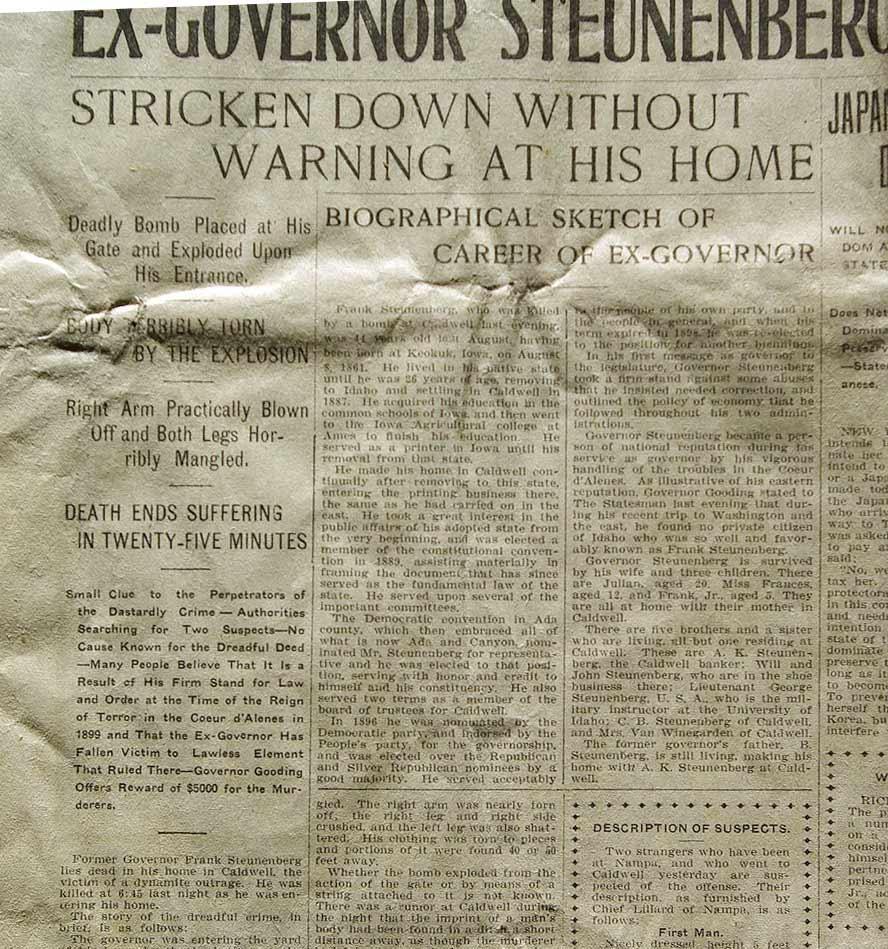

The Idaho Daily Statesman

Boise, Idaho Sunday Morning December 31, 1905

STRICKEN DOWN WITHOUT WARNING AT HIS HOME

Deadly Bomb Placed at His Gate and Exploded Upon His Entrance

BODY TERRIBLY TORN BY THE EXPLOSION

Right Arm Practically Blown Off and Both Legs Horribly Mangled

DEATH ENDS SUFFERING IN TWENTY-FIVE MINUTES

Small Clue to the Perpetrators of the Dastardly Crime – Authorities Searching for Two Suspects – No Cause Known for This Dreadful Deed – Many People Believe That It Is a Result of His Firm Stand for Law and Order at the Time of the Reign of Terror in the Coeur d’Alenes in 1899 and That the Ex-Governor Has Fallen Victim to Lawless Element That Ruled There – Governor Gooding Offers Reward of $5000 for the Murderers.

Former Governor Frank Steunenberg lies dead in his home in Caldwell, the victim of a dynamite outrage. He was killed at 6:45 last night as he was entering his home. The story of the dreadful crime, in brief, is as follows: The governor was entering the yard of his home by the back gate at the hour named when a terrible explosion…

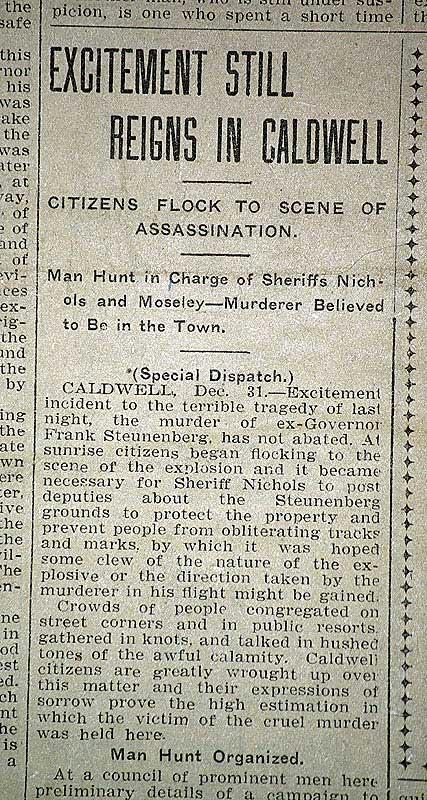

Special Dispatch

Caldwell, Dec. 31

Man Hunt in Charge of Sheriffs of Nichols and Moseley – Murderer Believed to Be in Town

Excitement incident to the terrible tragedy of last night, the murder of ex-Governor Frank Steunenberg, has not abated. At sunrise citizens began flocking to the scene of the explosion and it became necessary for Sheriff Nichols to post deputies about the Steunenberg ground to protect the property and to prevent people from obliterating tracks and marks, by which it was hoped some clew of the nature of the ex-…

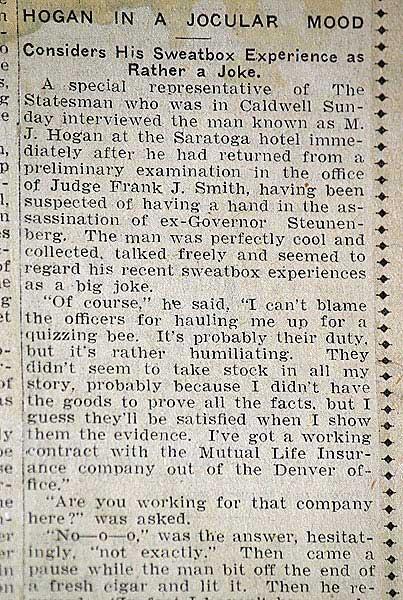

Considers His Sweatbox Experience as Rather a Joke

A special representative of the Statesman who was in Caldwell Sunday interviewed the man known as M.J. Hogan at the Saratoga hotel immediately after he had returned from a preliminary examination in the office of Judge Frank J. Smith, having been suspected of having a hand in the assassination of ex-Governor Steunenberg. The man was perfectly cool and collected, talked freely and seemed to regard his recent sweatbox experiences as a big joke.

“Of course,” he said, “I can’t blame the officers for hauling me up for a quizzing bee. It’s probably their duty, but it’s rather humiliating. They didn’t seem to take stock in all my story, probably because I didn’t have the goods to prove all the facts, but I guess they’ll be satisfied when I show them the evidence. I’ve got a working contract with the Mutual Life Insurance company out of the Denver office.”

“Are you working for that company here?” was asked.

“No-o-o,” was the answer hesitantly, “not exactly.” Then came a pause while the man bit off the end of a fresh cigar and lit it. Then he re-…

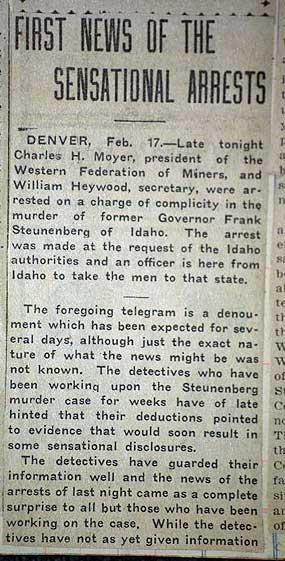

Denver, Feb. 17

Late tonight, Charles H. Moyer, President of the Western Federation of Miners, and William Haywood, secretary, were arrested on a charge of complicity in the murder of former Governor Frank Steunenberg of Idaho. The arrest was made at the request of the Idaho authorities and an officer is here from Idaho to take the men to that state.

The forgoing telegram is a denoument, which has been expected for several days, although just the exact nature of what the news might be was not known. The detectives who have been working upon the Steunenberg murder case for weeks have of late hinted that their deductions pointed to evidence that would soon result in some sensational disclosures.

The detectives have guarded their information well and the news of the arrests of last night came as a complete surprise to all but those who have been working on the case. While the detectives have not as yet given information…

A Mysterious Stranger Arrested in a Caldwell Hotel

Caldwell, Idaho, Jan. 1. The officers believe they have one of the men responsible for the assassination of ex-Gov. Steunenberg.

He is one of those who have been under suspicion. This man registered at the Saratoga Hotel three weeks ago as H.J. Hoglan, giving his address as Denver. A year ago he stopped at the Pacific hotel, registering as Thomas Hoglan. A search of his room at the Saratoga hotel resulted in the discovery of an overcoat and some other rough clothing; also some fish lines similar to the pieces found at the scene of the explosion, supposed to be…

“The state of Idaho will pay $2000 for the capture of Jack Simpkins, wanted on charge of the murder of ex-Governor Steunenberg.” That was the statement made last evening by Governor Frank R. Gooding. This offer doubles the original reward for the capture of Simpkins.

It was stated last night by the officials, and their belief is based upon reports from the north from parties who have been searching through the various camps in the Coeur d’Alene district for days, that Jack Simpkins is still in hiding.

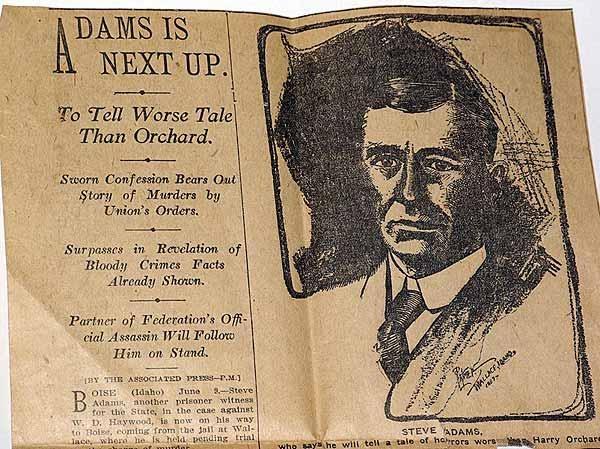

To Tell Worse Tale Than Orchard.

Sworn Confession Bears Out Story of Murders by Union’s Orders.

Surpasses in Revelation of Blood Crimes Facts Already Shown.

Partner of Federation’s Official Assassin Will Follow Him on Stand.

(By the Associated Press -- P.M.)

Boise (Idaho) June 9 – Steve Adams, another prisoner witness for the State, in the case against W.D. Haywood, is now on his way to Boise, coming from the jail at Wallace, where he is held pending trial…

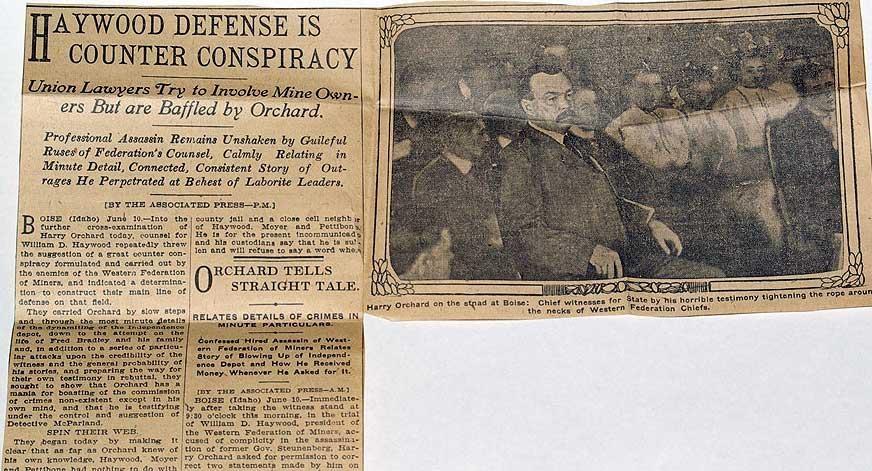

Union Lawyers Try to Involve Mine Owners But are Baffled by Orchard

Professional Assassin Remains Unshaken by Guileful Ruse of Federation’s Counsel, Calmly Relating in Minute Detail Connected, Consistent Story of Outrages He Perpetrated at Behest of Laborite Leaders

(By the Associated Press – P.M.)

Boise, (Idaho), June 10 – Into the further cross-examination of Harry Orchard today, counsel for William D. Haywood repeatedly threw the suggestion of a great counter conspiracy, formulated and carried out by the enemies of the Western Federation of Miners, and indicated a determination to construct their main line of defense on that field.

They carried Orchard by slow steps and through the most minute details of the dynamiting of the Independence depot, down to the attempt on the life of Fred Bradley and his family, and in addition to a series of particular attacks upon the credibility of the witness and the general probability of his stories, and preparing the way for…

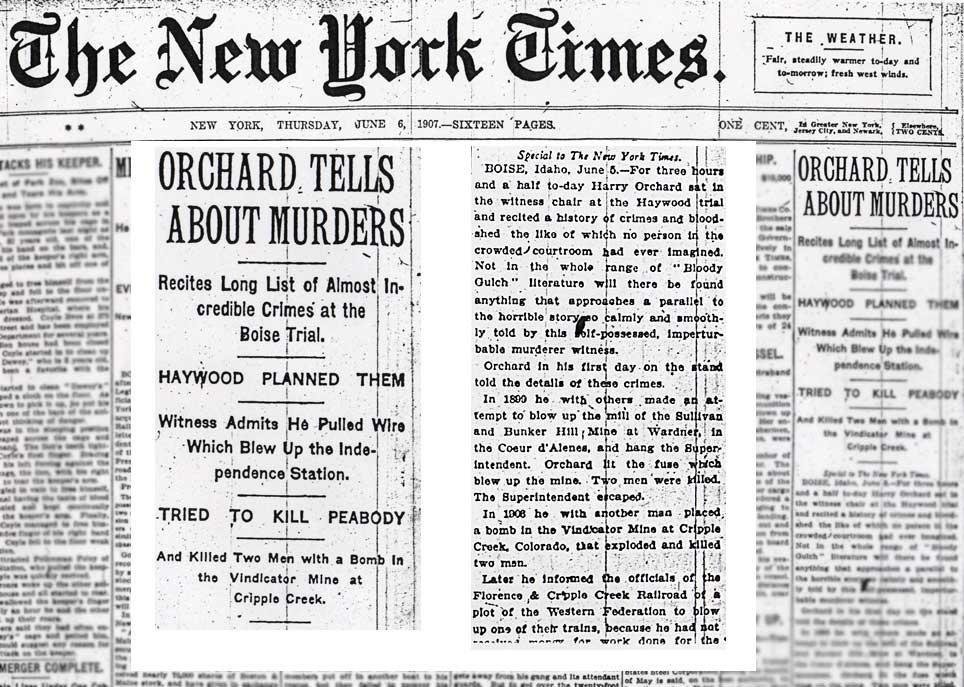

THE NEW YORK TIMES THURSDAY, JUNE 6, 1907

Recites Long List of Almost Incredible Crimes at the Boise Trial

HAYWOOD PLANNED THEM

Witness Admits He Pulled Wire Which Blew Up the Independence Stations And Killed Two Men with a Bomb in the Vindicator Mine at Cripple Creek.

TRIED TO KILL PEABODY

And Killed Two Men with a Bomb in the Vindicator Mine at Cripple Creek

Special to the New York Times Boise, Idaho, June 5.

For three hours and a half today Harry Orchard sat in the witness chair at the Haywood trial and recited a history of crimes and bloodshed, the like of which no person in the crowded courtroom had ever imagined. Not in the whole range of "Bloody Gulch" literature will there be found anything that approaches a parallel to the horrible story so calmly and smoothly told by this self-possessed, imperturbable murderer witness.

Orchard in his first day on the stand told the details of these crimes. In 1906 he with another man placed a bomb in the Vindicator Mine at Cripple Creek, Colorado, that exploded and killed two men. Later he informed the officials of the Florence and Cripple Creek Railroad of a plot of the Western Federation to below up one of their trains, because he had not received money for work done for the federation. He watched the residence of Gov. Peabody of Colorado and planned his assassination by shooting. This was postponed for reasons of policy. He shot and killed a deputy, Lyle Gregory, in Denver. He planned and with another man executed the blowing up of the railway station at the Independence Mine at Independence, Col., which killed fourteen men. He tried to poison Fred Bradley, manager of the Sullivan and Bunk Hill mine, then living in San Francisco, by putting strychnine into his milk when it was left at his door in the morning. This failed, and in November, 1904, he arranged a bomb which blew Bradley into the street when he opened his door in the morning.

Orchard Entirely Untroubled

Orchard spoke in a soft, purring voice, marked by a slight Canadian accent, and except for the first few minutes that he was on the stand he went through his awful story as undisturbed as if he were giving the account of a May Day festival. When he said, "and then I shot him," his manner and tone were as matter-of-fact as if the words had been "and then I bought a drink." There was nothing theatrical about the appearance on the stand of this witness, upon whose testimony the whole case against Haywood, Moyer, and the other leaders of the Western Federation of Miners is based. Only once or twice was there a dramatic touch. It was a horrible, revolting, sickening story, but he told it as simply as the plainest narration of the most ordinary incident of the most humdrum existence. He was neither a braggart nor a sycophant. He neither boasted of his fearful crimes nor sniveled in mock repentance.

It was just a plain recital of personal experience, and as it went on, hour after hour, with multitudinous detail, clear and vivid here, half forgotten and obscure there, gradually it forced home to the listener the conviction that it was the unmixed truth. Lies are not made as complicated and involved as that story. Fiction so full of incident, so mixed of purpose and cross-purpose, so permeated with the play of human passion, does not spring offhand from the most marvelous fertile invention. Touching continually points on which there can be controversy, Orchard explained acts whose motive until to-day had been hidden, whose purpose had remained a mystery. And while he talked the half-stifled crowd in the packed courtroom was so quiet that his soft voice penetrated to the furthest corner.

Haywood's Unwavering Attention

To Haywood the story was of vital interest. He sat with his lawyers surrounding him in such position that he could fix his gaze on Orchard uninterruptedly, but so placed that only those very near his chair could see his face. From first to last he gave unwavering attention, and when occasionally Orchard turned his eyes on his old comrade, whom he was denouncing as a procurer of assassination. Haywood met them squarely and unflinchingly.

Mrs. Haywood sat beside her husband all day, but their daughters did not come to court until afternoon. Haywood's mother, Mrs. Crothers, and his half-sister, Miss Crothers, sat near his wife. Mrs. Crothers is a pleasant-looking, spectacled old lady, whose black hair is strongly tinged with gray. The lower part of her face much resembles that of her son, except that the mouth is better matured, with corners that turn up instead of down. Mrs. Steve Adams and Mrs. Pettibone, with Mrs. Haywood's sister, were in court all day, and seemed especially aroused at those parts of Orchard's story which involved Adams and Pettibone. Whenever Orchard told of Adams being drunk, as he did on several occasions, Mrs. Adams smiled as if it were a joke.

The courtroom was not even filled when Orchard was called to the stand. It was known that he had been brought in from the penitentiary last, and would not come in until the afternoon session. When court opened at 9 o'clock Senator Borah went on with the line of proof he was developing yesterday afternoon, and summoned several hotel keepers to prove that Orchard and Jack Simpkins had been together at Caldwell and other places near there in the Fall of 1905, before the Steunenberg murder. Men from Caldwell, Nampa, and Silver City identified their registers and, the signature of Orchard and Simpkins, or Simmons, as he sometimes called himself.

Then a young bank clerk from Wallace came on, who told of having taught Simpkins to write. He identified as that of Simpkins the photograph which was identified yesterday by two or three men as that of Simmons, thus establishing that the Simmons who was with Orchard at Caldwell before the murder was in fact Jack Simpkins. He also identified as the writing of Simpkins the signatures of Simmons in the different hotel registers. When the bank clerk was excused, Senator Borah remarked casually, as if it was a matter of no particular interest, "The next witness will be here in a few minutes."

Orchard's Entrance

Of course that was Orchard. A rustle went through the courtroom at the announcement and there was a general shifting of seats to get down as near the front as possible. The day was warm and the room was hot and stuffy, but those who had the lucky seats near the windows cheerfully gave them up for the chance of sitting nearer the witness chair, that stands directly in front of the bench facing the jury. It is between the two long tables which stand one at each side and in front of the jury box for the accommodation of the lawyers.

In front of the witness chair, and almost touching it, are the tables of the stenographers, separating the lawyer’s tables. This places the witness some fifteen feet from the front row of jurors and about half that distance from the lawyers. Haywood sits at the end of the table used by his attorneys, almost within arm's reach of Juror No. 6.

Orchard had been kept over night at Hawley's office, under guard of Deputy Sheriffs, penitentiary guards, and detectives. They had not expected the summons for him so soon, and it was about ten minutes after Borah's announcement that he reached the Court House, having been brought up in a carriage surrounded by guards. He was brought up from the Sheriff's office by the back stairs built especially for this trial. The crowd had been craning their necks to get a better look at the door, and twisting from the main entrance to the side door, uncertain at which Orchard would appear. Darrow, Peter Breen, the new lawyer sent down to help the defense by the Butte unions, and Mrs. Crothers were chatting together over some amusing subject that brought smiles to all their faces, and Haywood was busily talking with Richardson and Nugent, when the side door, which had been opened, was closed from the outside and everybody knew that Orchard had arrived.

"Call Harry Orchard." said Senator Borah. The side door opened and Ras Beemer, the gigantic Deputy Sheriff who has charge of the prisoners at the jail, entered, followed closely by Orchard, behind whom came four or five guards and detectives. Instantly there was a movement in the back part of the courtroom. Several persons rose t their feet to get a better look and several started forthwith toward the rail which separates the bar enclosure from the body of the room. There had been so much talk of a possible attempt to do harm to Orchard when he should come on the witness stand that the guards and deputies were on the alert to check the first indication of any such thing. As the spectators rose in the rear of the room, two or three of the deputies jumped toward them with outstretched hands.

Deputies Keep Order

"Sit down!" shouted one of the Deputies in a voice that carried clear beyond the Court House lot. There was a ring of earnestness in the command that made it obeyed on the instant, and at once the courtroom became entirely quiet. Meantime, Beemer and Orchard had marched on in the gate in the railing by the witness chair. Beemer opened the gate and let Orchard through. Then he dropped the bar again and stood outside the rail. For a moment Orchard seemed dazed and uncertain what to do. He turned partly toward the defendant's table, but his gaze did not meet Haywood. The clerk was standing with uplifted hand waiting to administer the oath, but Orchard did not see him.

Beemer reached across the gate bar, took Orchard by the shoulder, and turned him half around so that he saw the clerk. Mechanically he raised his right arm. The forefinger was held straight, but the others were closed. His face was deadly pale and his lips twitched nervously. He was plainly under a great strain. But he responded to the oath in a clear voice, climbed up into the high witness chair, and sat down with evident relief.

Every eye in the courtroom was on him. Haywood's lawyers were learning forward to get a better look and between them Haywood crouched down so that he was concealed from all except those directly in front of him, stared with a look so fixed and hard that it seemed as if it would bore through Orchard. Every juror was staring hard at Orchard, most of them sitting forward on the edge of their chairs as if they half expected some desperate thing to happen then and there. The moment that Haywood appeared and from then on to the end of the day, no feature of the awful story he related affected him so as to alter his demeanor or shake his composure.

He told first the story of his birth in North Cumberland County, Ontario, forty-one years ago, and gave his true name as Albert E. Horsley. He has used the name of Orchard for eleven years, ever since he came to the United States from Canada. Why he came or why he changed his name was not brought out, although the reason for both must have a bearing on the subsequent career he led. He was a cheese maker in Canada, and when he came to this State from there he drove a milk wagon for a time and then owned and ran a wood yard up in the Coeur d’Alene’s.

What had happened to predispose this follower of such peaceful occupations to the life of atrocious crime he afterward led has not been disclosed. From giving these details of his uneventful, law-abiding existence, he went on to the narration of the most astounding stories of murder and assassination ever told in a courtroom, at least since the days of the Mollie Maguires. He began it, by his own admission, within a month after selling his wood yard and joining the Miner's Union at Burke.

No reason of compulsion or solicitude by the leaders of the union was shown for that crime. Apparently he committed it for the pure love of it. It did not involve bloodshed directly, as most of the later crimes did, but it was the sure forerunner of such. It was the blowing up of the Bunker Ill and Sullivan Mill at Wardner, on April 29, 1898, the crime that led to the military campaign in the Coeur d'Alenes that summer, and laid the foundation for the murder of Steunenberg. Simply, directly, in his quiet purring voice, Orchard told of the special meeting of his union called that morning, of his own attendance, and of the argument between Paul Corcoran, the Secretary, and Bill Devery, the President, over the proposition to go to Wardner and destroy the mill "and hang the Superintendent." By a bare majority vote, he said, the Burke Union decided to go. It was when he came to the blowing up of the mill that he confessed his first crime. Three fuses were laid.

His First Admission

"Who lit them?" asked Hawley. "I lit one," replied Orchard calmly, "I don't know who lit the others." A gasp of astonishment came from all over the courtroom. The crowd had been expecting to hear a tale of murder and killing, but somehow it seemed to have expected something different in the telling from this, and was not prepared for this sudden, simple, undemonstrative announcement. It came so quietly, so unexpectedly that it took the breath away.

Richardson fought vigorously to keep out the story. He objected at every point, protesting that there was not a thing in all this to connect Haywood with the murder of Steunenberg, and doing his best to limit the story of that tragedy. But Hawley and Borah beat him every time. Not the murderers of Steunenberg alone are on trial now, but this inner circle of the Western Federation of Miners, and not only for the Steunenberg killing, but for the terrible list of bloody crimes that Orchard went on to give. "On what theory can it be shown that Haywood was responsible for all of this?" cried Richardson, "when he was not connected with the Federation in an official capacity until more than a year afterward?"

"The theory of the State is that out of this trouble grew the feeling against Steunenberg which prevailed in the inner circle when Haywood later became a member of it," replied Senator Borah, "the feeling which directly caused that murder. Haywood became a partisan of the Western Federation and had that feeling, and on that we shall show his responsibility."

State Wins on Rulings

The State won. It won on every contest and in the end it became simply a matter of formal making of the objection and noting of the exception to the adverse ruling. It became apparent that Judge Wood had studied for himself the question of the admission of this evidence. He had foreseen what the State would attempt to do, and had prepared himself in advance for the rulings he would have to make. To his mind the only question was as to whether all this testimony would be connected directly with Haywood and the Steunenberg murder. Hawley and Borah assured him that unquestionably it would be so connected and he admitted it. That was the first great legal obstacle to be overcome by the State. The manner in which it won today justified the presumption that the question of the admissibility of its evidence as to the general conspiracy it charges has been settled in its favor.

As a point bearing on the motive for the Steunenberg murder Hawley brought out part of Paul Corcoran's argument in the Burke union meeting on the morning of the destruction of the Bunker Hill and Sullivan Mills. "Corcoran said that there would be no trouble with Steunenberg." said Orchard, with the manner of one who recalls the incidents of a picnic of last week. "He said the unions had always supported Steunenberg and owned him. We only had to look out for the regulars."

Steunenberg's Murder Planned

It was their disappointment at the failure of Steunenberg to live up to this estimate of him, the State contends, that led the inner circle men to plan his murder. From the account of that day and his flight from Burke and the regulars, Orchard went through the story of his wanderings in various mining districts in Utah, California, Nevada, and elsewhere for three years or more, until at length in July, 1902, he reached the Cripple Creek area. He worked for men whose motives he did not concern himself about. They set his tasks and he executed them, and there was never a question because high or low, great or small was marked for death; when the quarry was named he set out on his work, and when it had been accomplished he reported his successes.

That was all, he took the commendation of his employers as it came, all in the day's work, and neither strove neither to merit it nor to avoid their condemnation. It was money he worked for, and very little of that. The astonishing tale is utterly incredible, and yet there is that in the manner and bearing of the teller that stamps it as true. What motive he has for telling it now has not yet been disclosed. He told me a few weeks ago at the penitentiary some facts about his life since his arrest for the Steunenberg murder which afford a reasonable explanation.

Tries to Atone

He said that a man who had done a great wrong in his life could never hope to atone for all of it, but he believed that he ought to do what he could to set matters as far straight as possible. He told me that in just the same simple matter of fact way that he told his gruesome story to-day. I believed him then.

Today he forced on me the conviction that he was telling what had happened as it occurred. He has got beyond caring what comes to himself as the result. He does not even attempt to shield himself in any of the details.

He simply narrates an astounding and incredible series of events, in telling what this or that man did or said and what he himself said and did, with just the same monotony of narration as if he were recounting the uninteresting incident of his life as a cheese maker in Canada ten or a dozen years ago.

So it was when he told of the blowing up of the Vindicator shaft at Cripple Creek and the killing of McCormick and Beck, manager and shift boss of the mine. So it was when he narrated the attempt he made to blow up Bradley in San Francisco on the old grudge held against him ever since 1899 because he was owner of the Bunker Hill and Sullivan mines; so, too, it was when he described the ghastly massacre of non-union men at the Independence Depot because Haywood thought it necessary to get up some excitement to prevent a split in the Federation.

He told of putting strychnine in the milk left on Bradley's doorstep as if he had described changing the bottles for four pails of ice cream. He told of pulling the wire that exploded the bomb at Independence as he might have told of hauling a fish out of the water. There was never a change in color in his ruddy face as these stories of murder fell from his lips. Not even the tale of the killing of Lyle Gregory, the drunken Deputy Sheriff whom he followed about the streets of Denver in the night and shot in the back, brought a quiver in his voice or a tear to his eyes. Never a man like this sat in the witness chair before.

Haywood the Master

Through all the story ran the names of the men for whom he worked and those who helped him in his wretched tasks. Haywood as the master. It was he who gave most of the orders. Pettibone, too, gave directions, furnished money, and once started out as if to help, but made excuse and turned back. That was in the Gregory murder. Haywood was the source of the money. Even what Pettibone gave him came from Haywood. Moyer he named occasionally, but not often. Moyer knew of some of the crimes, for he talked to Orchard about them and joined in Haywood's declaration that this or that "was a fine job."

But Haywood was the master, with Pettibone as the chief assistant, and then there were W. F. Davis, the old Coeur d'Alene comrade, and Sherman Parker and Charley Kennison of the district union, with W. B. Easterly Financial Secretary of Orchard's own union. Parker is dead now, shot a little while ago in Goldfield.

The defense professed to be pleased with the story as one that disproved itself. The prosecution, however, is sure it can be corroborated. Without question it produced a tremendous effect, and throughout its recital there ran a growing conviction of its truth.

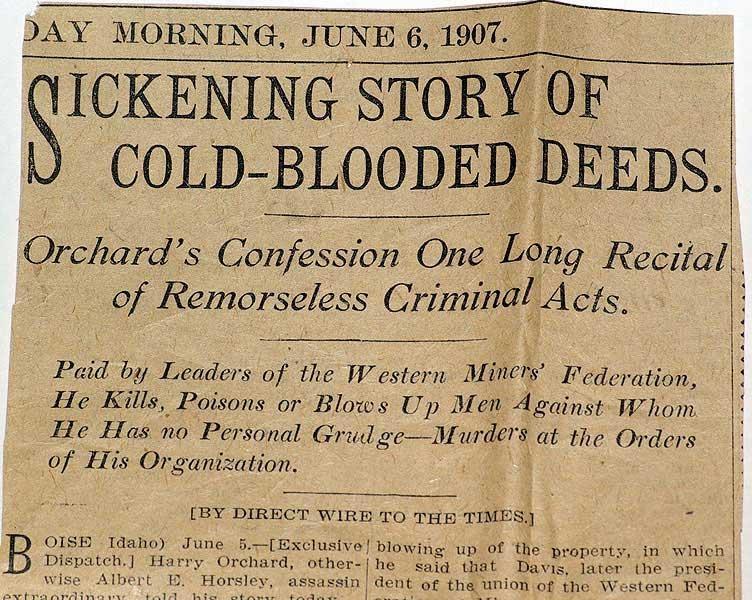

Orchard’s Confession One Long Recital of Remorseless Criminal Acts.

Paid by Leaders of the Western Miners’ Federation, He Kills, Poisons, or Blows Up Men Against Whom He Has no Personal Grudge – Murders at the Orders of His Organization.

(By Direct Wire to the Times.)

Boise, Idaho June 5 – (Exclusive Dispatch)

Harry Orchard, otherwise Albert E. Horsley, assassin extraordinary told his story today…

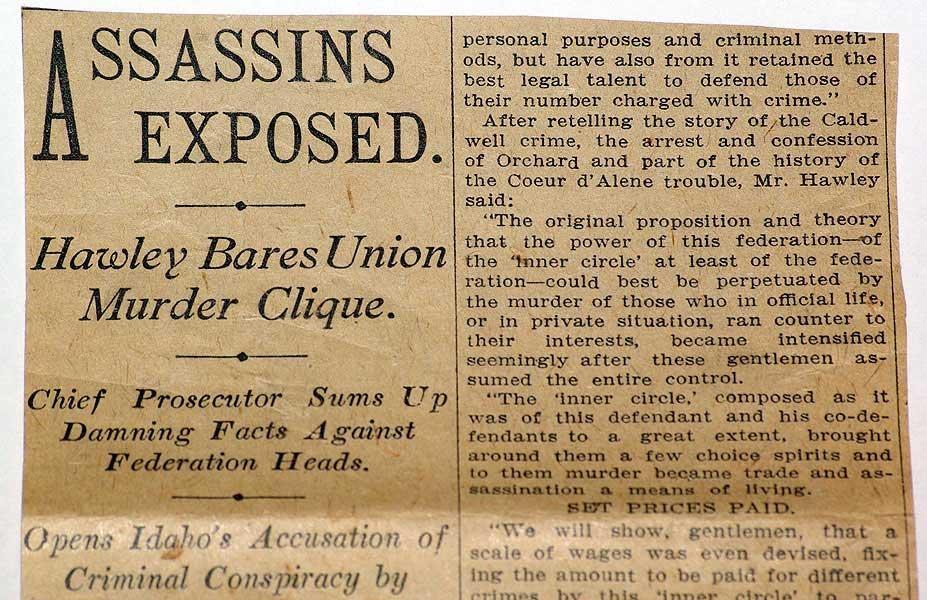

Hawley Bares Union Murder Clique

Chief Prosecutor Sums Up Damning Facts Against Federation Heads.

Opens Idaho’s Accusation of Criminal Conspiracy by…

…personal purposes and criminal methods, but have also from it retained the best legal talent to defend those of their number charged with crime.”

After retelling the story of the Caldwell crime, the arrest and the confession of Orchard, and part of the history of the Coeur d’Alene trouble, Mr. Hawley said:

The original proposition and theory that the power of this federation -- of the ‘inner circle’ at least of the federation – could best be perpetuated by the murder of those in official life, or in private situation, ran counter to their interests, became intensified seemingly after these gentlemen assumed the entire control.

“The ‘inner circle,’ composed as it was of this defendant and his co-defendants to a great extent, brought around them a few choice spirits and to them murder became trade and assassination a means of living.

SET PRICES PAID

“We will show, gentlemen, that a scale of wages was even devised, fixing the amount to be paid for different crimes by this ‘inner circle’ to par-…

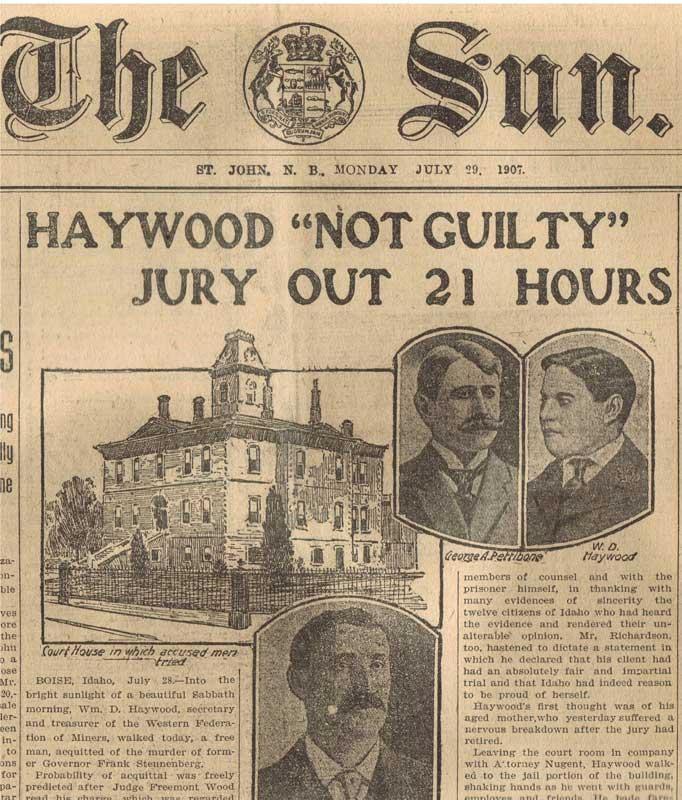

The Sun. St. John, N.B. Monday, July 29, 1907

Boise, Idaho, July 28. Into the bright sunlight of a beautiful Sabbath morning, Wm. D. Haywood, secretary and treasurer of the Western Federation of Miners, walked today, a free man, acquitted of the murder of former Governor Frank Steunenberg.

Probability of acquittal was freely predicted after Judge Fremont Wood read his charge, which was regard…

Members of counsel and with the prisoner himself, in thanking with many evidences of sincerity the twelve citizens of Idaho who had heard the evidence and rendered their unalterable opinion. Mr. Richardson, too, hastened to dictate a statement in which he declared that his client had had an absolutely fair and impartial trial and that Idaho had indeed reason to be proud of herself.

Haywood’s first thought was of his aged mother, who yesterday suffered a nervous breakdown after the jury had retired.

Leaving the court room in company with Attorney Nugent, Haywood walked to the jail portion of the building, shaking hands as he went with guards, employees, and friends. He bade fare-…

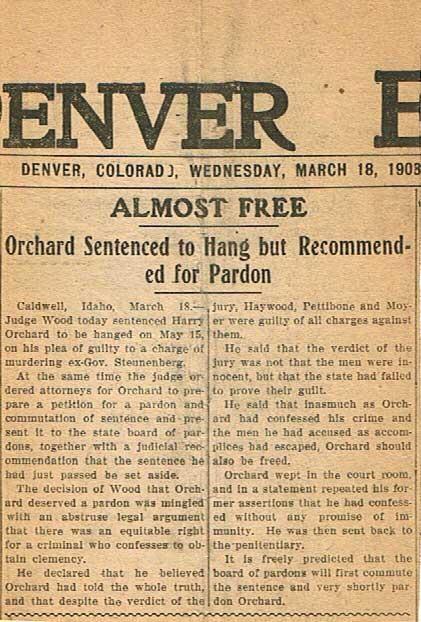

Denver, Colorado, Wednesday, March 18, 1908

Orchard Sentenced to Hang But Recommended for Pardon

Caldwell, Idaho March 18

Judge Wood today sentenced Harry Orchard to be hanged on May 15, on his plea of guilty to a charge of murdering ex-Gov. Steunenberg.

At the same time the judge ordered attorneys for Orchard to prepare a petition for a pardon and commutation of sentence and present it to the state board of pardons, together with a judicial recommendation that the sentence he had just passed be set aside.

The decision of Wood that Orchard deserved a pardon was mingled with an abstruse legal argument that there was an equitable right for a criminal who confesses to obtain clemency.

He declared that he believed Orchard had told the whole truth, and that, despite the verdict of the jury, Haywood, Pettibone, and Moyer were guilty of all charges against them.

He said that the verdict of the jury was not that the men were innocent, but that the state had failed to prove their guilt. He said that inasmuch as Orchard had confessed his crime and the men he had accused as accomplices had escaped, Orchard should also be freed.

Orchard wept in the court room and in a statement repeated his former assertions that he had confessed without any promise of immunity. He was then sent back to the penitentiary.

It is freely predicted that the board of pardons will first commute the sentence and very shortly pardon Orchard.

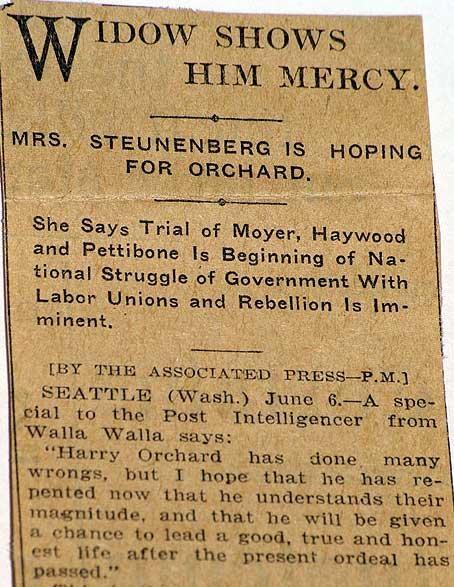

Mrs. Steunenberg is Hoping for Orchard.

She Says Trial of Moyer, Haywood, and Pettibone is Beginning of National Struggle of Government With Labor Unions and Rebellion is Imminent.

(By the Associated Press – P.M.) Seattle, Washington, June 6

A Special to the Post Intelligencer from Walla Walla says: “Harry Orchard has done many wrongs, but I hope that he has repented now that he understands their magnitude, and that he will be given a chance to lead a good, true, and honest life after the present ordeal has passed.”

Idaho Daily Statesman

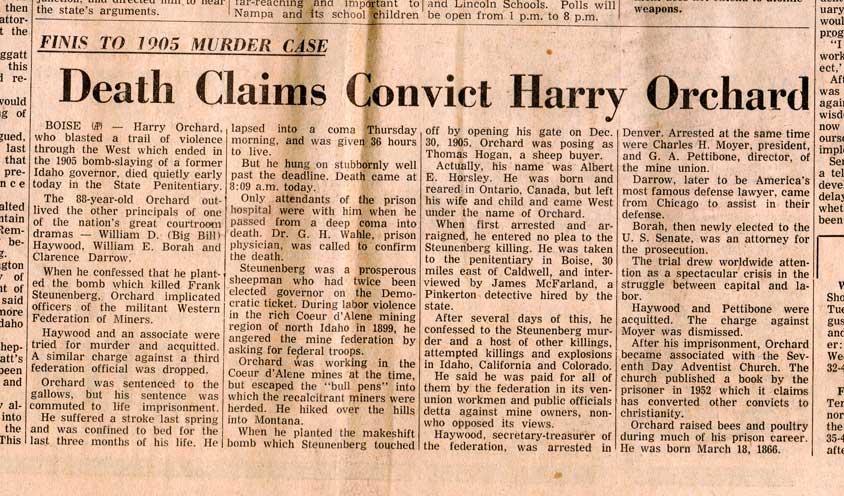

Death Claims Convict Harry Orchard

Harry Orchard, who blasted a trail of violence through the West which ended in the 1905 bomb-slaying of a former Idaho governor, died quietly today in the State Penitentiary.

The 88-year old Orchard outlived the other principals of one of the nation’s great court room dramas – William D (Big Bill) Haywood, William E. Borah, and Clarence Darrow.

When he confessed that he planted the bomb which killed Frank Steunenberg, Orchard implicated officers of the militant Western Federation of Miners.

Haywood and an associate were tried for murder and acquitted. A similar charge against a third federation official was dropped. Orchard was sentenced to the gallows, but his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. He suffered a stroke last spring and was confined to bed for the last three months of his life. He lapsed into a coma Thursday morning, and was given 36 hours to live.

But he hung on stubbornly well past the deadline. Death came at 8:09 a.m. today.

Only attendants of the prison hospital were with him when he passed from a deep coma into death. Dr. G. H. Wahle, prison physician, was called to confirm the death.

Steunenberg was a prosperous sheepman who had twice been elected governor on the Democratic ticket. During labor violence in the rich Coeur d’Alene mining region of north Idaho in 1899, he angered the mine federation by asking for federal troops.

Orchard was working in the Coeur d’Alene mines at the time, but escaped the “bull pens” into which recalcitrant miners were herded. He hiked over the hills into Montana.

When he planted the makeshift bomb which Steunenberg touched off by opening his gate on Dec. 30, 1905, Orchard was posing as Thomas Hogan, a sheep buyer.

Actually, his name was Albert E. Horsley. He was born and reared in Ontario, Canada, but left his wife and child and came west under the name of Orchard.

When first arrested and arraigned, he entered no plea to the Steunenberg killing. He was taken to the penitentiary in Boise, thirty miles east of Caldwell, and interviewed by James McFarland [sic], a Pinkerton detective hired by the state.

After several days of this, he confessed to the Steunenberg murder and a host of other killings and explosions in Idaho, California and Colorado.

He said he was paid for all of them by the federation in its vendetta against mine owners, nonunion workmen and public officials who opposed its views.

Haywood, secretary-treasurer of the federation, was arrested in Denver. Arrested at the same time were Charles H. Moyer, President, and G. A. Pettibone, director, of the mine union.

Darrow, later to be America’s most famous defense lawyer, came from Chicago to assist in their defense. Borah, then newly elected to the U.S. Senate, was an attorney for the prosecution.

The trial drew worldwide attention as a spectacular crisis in the struggle between capital and labor. Haywood and Pettibone were acquitted. The charge against Moyer was dismissed.

After his imprisonment Orchard became associated with the Seventh Day Adventist Church. The Church published a book by the prisoner in 1952 which it claims has converted other convicts to Christianity.

Orchard raised bees and poultry during much of his prison career. He was born March 18, 1866.

Two Reporters' Perspectives

Oscar King Davis of the venerable New York Times and Ida Crouch Hazlett of the tiny Socialist paper, The Montana News, presented two very different views of the Haywood trial.

Their opinions about the truthfulness of Harry Orchard's testimony — and thus the guilt of "Big Bill" Haywood — were diametrically opposed. But they shared one thing in common: an ability to write wonderfully descriptive sentences.

The national press flocked to Boise, Idaho, in the summer of 1907. Joining Davis and Hazlett were correspondents from the Associated Press, The Hearst, Pulitzer, Scripps, and New York Sun, as well as The Denver Post, Boston Globe, Portland Evening Telegram, Cleveland Press, Chicago Herald-Record and Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

Through his daily reports, O.K. Davis kept the world informed of every nuance of the trial. Hazlett's audience was considerably smaller, but she also presented a first person account of the court room events in the summer of 1907.

Here are their impressions of the dramatic testimony of Harry Orchard in June of 1907.

BOISE, Idaho, June 5—For three hours and a half today Harry Orchard sat in the witness chair at the Haywood trial and recited a history of crimes and bloodshed, the like of which no person in the crowded courtroom had ever imagined. Not in the whole range of "Bloody Gulch" literature will there be found anything that approaches a parallel to the horrible story so calmly and smoothly told by this self-possessed, imperturbable murderer witness.

There was nothing theatrical about the appearance on the stand of this witness, upon whose testimony the whole case against Haywood, Moyer, and the other leaders of the Western Federation of Miners is based. Only once or twice was there a dramatic touch. It was a horrible, revolting, sickening story, but he told it as simply as the plainest narration of the most ordinary incident of the most humdrum existence. He was neither a braggart nor a sycophant. He neither boasted of his fearful crimes nor sniveled in mock repentance.

It was just a plain recital of personal experience, and as it went on, hour after hour, with multitudinous detail, clear and vivid here, half forgotten and obscure there, gradually it forced home to the listener the conviction that it was the unmixed truth. Lies are not made as complicated and involved as that story. Fiction so full of incident, so mixed of purpose and cross-purpose, so permeated with the play of human passion, does not spring offhand from the most marvelous fertile invention. Touching continually points on which there can be controversy, Orchard explained acts whose motive until to-day had been hidden, whose purpose had remained a mystery. And while he talked the half-stifled crowd in the packed courtroom was so quiet that his soft voice penetrated to the furthest corner.

The astonishing tale is utterly incredible, and yet there is that in the manner and bearing of the teller that stamps it as true. What motive he has for telling it now has not yet been disclosed. He told me a few weeks ago at the penitentiary some facts about his life since his arrest for the Steunenberg murder which afford a reasonable explanation.

He said that a man who had done a great wrong in his life could never hope to atone for all of it, but he believed that he ought to do what he could to set matters as far straight as possible. He told me that in just the same simple matter of fact way that he told his gruesome story to-day. I believed him then. Today he forced on me the conviction that he was telling what had happened as it occurred. He has got beyond caring what comes to himself as the result. He does not even attempt to shield himself in any of the details.

Orchard looks neat, well-dressed in gray and well kept. But his face is certainly one of the most repulsive countenances that one is ever called to gaze upon. It is the face of a man without a soul, of one who has never known the call of the higher and nobler impulses. He is a man who would do anything for almost any consideration. He is of the born criminal type — with a certain intelligence to enable him to carry out his crime, but not enough to enable him to successfully cover them up.

Orchard's testimony was simply a repetition of what has already been published as his confession, and which he repeated as one who had learned a lesson well. Hawley led the way for him with questions — so much so that attorney Richardson accused him of testifying instead of the witness.

Orchard was a day and a half giving his testimony. The performance was a psychological study. The man has woefully missed his calling. He should have been a second Conan Doyle. Sherlock Holmes isn't in it beside him.

When one reads the testimony of Orchard, how he claims he murdered for money, the question arises, how much is he being paid to railroad Moyer, Haywood, and Pettibone to the scaffold?

It will be interesting to see what becomes of Orchard. It is safe to say that not a hair of his head will ever be harmed. He walks secure amid his enemies, among the men whose lives he seeks like a human hyena, surrounded by what his guardians consider the greatest dangers through the exaggerated care they take to provide against any possible harm to this darling of the gods of mammon.

Expert Commentary - Interviews

Historian Katherine Aiken is the Dean for the College of Letters, Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Idaho. Her latest book is Idaho's Bunker Hill: The Rise and Fall of a Great Mining Company, 1885-1925. This interview was conducted in January of 2007.

BR: What were working conditions like in the 1890's in Idaho's Coeur d'Alene mining district?

KA: Mining — not just then, but now — is incredibly dangerous work. People didn't have protective equipment, they worked incredibly long hours in conditions that were hot and wet and uncomfortable. The physical amount of labor was tremendous, and the nature of the work was uncertain. You didn't know that you would have work over an extended period of time; and so, when prices went down or supplies were too high or for whatever reason, you would simply be unemployed, and there's no social welfare safety net that protects you.

We know that lead and mercury and other elements that were underground are dangerous; and particularly once they started using machine drills, and there's lots of dust, miner silicosis is a terrible problem in all mining in the west. Life expectancy was not long and people who contracted that disease had a very long and painful death ahead of them.

And mine owners were determined that skilled miners should receive $3.50; but other people who work underground — primarily muckers, the people who shovel rock into ore carts and ship it out of the mine — should receive less money, $3.00. Miners saw that as an assault on their dignity as workers, and they refused to entertain that idea.

BR: Folks might be surprised at the amount of violence in northern Idaho.

KA: There are two major incidents of violence in the Coeur d'Alenes: one in 1892 and one in 1899, where martial law is declared and miners are incarcerated in so-called "bull pens," makeshift jails. There simply weren't permanent jails there to accommodate that many people when you've arrested them; but there actually is ongoing violence throughout the 1890's in various ways and in various locations, and that entire decade is a constant war between mine owners and miners.

The Western Federation of Miners is created in the wake of the 1892 episode of violence, where miners are arrested and imprisoned; and while they are in federal prison, they talk about what has happened to them, and they decide they never want that to happen to them again, and they create this organization. And I think the fact that it's called The Western Federation of Miners is illustrative of their notion that the western hard rock miner had a unique role to play in labor organization, and that they wanted an organization that represented them and only them and really understood their interests.

BR: What was the worst kind of violence that occurred in the Coeur d'Alene mining district?

KA: I suppose that depends on your perspective. From mine owners' perspective, the worst kind of violence was when their private property was destroyed. I would argue, and I think miners would argue, in the 1890's that they confronted violence every day when they were forced to go underground and confront these dangerous conditions, and how their families suffer from not having enough to eat and having poor housing and not having health care.

BR: How did the state of Idaho respond to the violence that involved dynamite?

KA: The sanctity of private property is a critical element of the American psyche; and even though oftentimes it was the case before the 1870's, '80's and '90's that local government in particular was more closely allied and more sympathetic to workers, by the time we get into the period that we're talking about, government took more seriously its role as protector of private property; and it chose business and management over other individuals, because that sanctity of private property was so important.

BR: How important was the Coeur d'Alene mining district to the nation and the world?

KA: The Coeur d'Alene mining district is probably the premiere mining district in the world, and certainly the single most important economic enterprise in the state of Idaho, and a huge producer and long term producer of metals that are central to allowing the United States to become an industrial power.

BR: What particular relationship did Frank Steunenberg have with unions and with the mine owners?