IdahoPTV Specials

Please note that this content is no longer being updated. As a result, you may encounter broken links or information that may not be up-to-date. For more information contact us.

Capitol of Light: The People's House

Idaho’s most significant and treasured structure has been given a facelift.

And Idaho Public Television was there to document the return to splendor of the grand old building.

Learn about the difficulties encountered along the way. Discover the stories that abound under the elegantly refurbished dome. Explore the fascinating history of the People’s House, known as the Capitol of Light.

Our Capitol

The nine-member Idaho State Capitol Commission is created and charged with completing a Master Plan for the restoration/renovation of the State Capitol Building.

The Legislature appropriates $120,000 and the design team of CSHQA/Isthmus is selected to develop the Master Plan.

2000The Master Plan is completed. The total cost of the project is estimated to be $64 million.

2001The Legislature provides a one-time appropriation of $32 million and authorizes the Commission to issue bonds for the remaining $32 million.

2002The restoration project is temporarily postponed because of projected shortfalls in state revenues. The Commission returns the $32 million appropriation to the State’s General Fund, and withdraws its request to issue bonds.

Nevertheless, the Commission is able to begin work on the restoration of the exterior of the Capitol. Between 2001 and 2002, about $1.5 million is appropriated for the Phase I Exterior Renovation.

2003The Legislature appropriates nearly $3 million to complete the Phase ll Exterior Renovation.

2005The Legislature revives hope for the interior restoration by extending the cigarette tax so that a portion of the revenue collected, beginning in FY07, is deposited into the Permanent Building Fund. The annual amount, estimated at $20 million, is earmarked for the repair, remodel, and restoration of the Capitol and state facilities pertaining to the Capitol restoration.

2006The Legislature authorizes the Capitol Commission and the Department of Administration to enter into agreements with the Idaho State Building Authority to finance the restoration and construction of two 2-story underground wings on each end of the Statehouse.

A total of $130 million is secured in bonds; McAlvain/Hummel, design/build professionals, is hired to begin work on the wings; and, the design team of CSHQA Architects and Lemley/3DI continues to finalize space-use plans of the existing building.

All exterior work is completed on the Capitol.

2007Governor Otter proposes that only the restoration of the existing Capitol be completed and not the addition of the 2-story underground wings. A compromise is reached, to proceed with the addition of two, 1-story underground wings and to reassign the use of the first floor of the Capitol to the Legislature rather than to the Executive Branch.

State officials, including the Governor, move to the old Federal Building, called the Borah Building. Serious work begins on the Capitol and the wings.

2008The Legislature meets in the old Ada County Courthouse—renamed the Capitol Annex—for the start of the legislative session.

Work continues on the Capitol restoration and the one-story underground wings on the east and west sides of the original Capitol building.

2009The Legislature again meets in the Capitol Annex; and work continues on the Capitol.

2010State government moves back to the stately Capitol for the legislative session that begins in January.

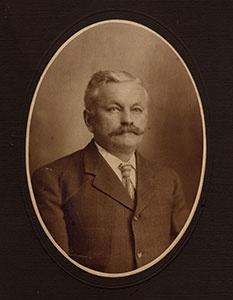

They were a partnership made in architectural heaven: John E. Tourtellotte, the brilliant designer and savvy promoter; and Charles F. Hummel, the classically trained architect and civil engineer.

Each provided what the other needed; in fact, you could say that Hummel brought structural strength to Tourtellotte's visionary ideas.

Today you might be inclined to use the phrase "right brain/left brain" to describe these two. Together, they created some of Idaho's remarkable buildings, including Boise's Carnegie Library and St. John's Cathedral, as well as the University of Idaho's Administration Building.

And they designed Idaho's iconic and stately Capitol.

The grandson of Charles Hummel, himself an architect and another Charles, put it this way: "Tourtellotte was the promoter, the visionary. He knew how to get work, and he knew how to talk. He was a designer of some capability. His tastes were pretty Victorian, rather ornate. My grandfather, who was classically trained as an architect in Germany, understood construction thoroughly, and he brought to the firm the classicizing side."

Tourtellotte moved to Boise in 1890. By 1903, he had formed J.E. Tourtellotte & Company. Hummel came to Boise in 1895 and joined the firm in 1903. Eventually, the world would come to know them as the architectural firm of Tourtellotte & Hummel.

For our documentary, we asked actor M.A. Taylor to play the role of John Tourtellotte; and we found our actor an old fashioned Dictaphone, which was in vogue at the turn of the century.

"My grandfather called it a 'talking machine,'" says grandson Charles Hummel. "The only person in the office who really used it in those days was Tourtellotte. That was his forte. He really knew how to promote and how to talk and how to get people to visualize buildings."

It was with the help of his "talking machine" that Tourtellotte composed his essays emphasizing the importance of light to good government.

Even though Tourtellotte and Hummel were well known to Boise residents, getting the commission to design Idaho's new capitol was not a slam dunk for the firm. They first had to beat out eighteen other architects from Idaho and back east. And it was not a unanimous vote by the Idaho Capitol Commission back in 1905. Governor Gooding wanted someone else. But finally, on the third ballot, Tourtellotte and Hummel prevailed.

Perhaps it was the emphasis on light that tipped the scale.

With Hummel by his side to give him a thumbs up or thumbs down on whether his drawings would actually stand up, Tourtellotte designed a capitol with light as its hallmark.

The building was to be flooded with light from skylights, and the interior would reflect light from stark white walls and light-colored marble. Color, when he used it, would pop.

Hummel's grandson has noticed. "Tourtellotte loved skylights, and that white marble and the white colored scagliola flooded with light is one of the real achievements of this capitol."

Or, as Tourtellotte himself wrote: "If the people are well balanced in their ideal and understand... that the great white light of conscience must be allowed to shine and by its interior illumination make clear the path of duty... then this Capitol truly represents the Commonwealth of Idaho."

The nine-member Commission was created by Governor Batt and the Legislature in 1998 and charged with completing a Master Plan for the restoration, refurbishment, and preservation of the State Capitol Building and its grounds, along with a funding program that combines public and private funds to implement the Master Plan.

The design team of CSHQA/Isthmus was chosen to develop the Master Plan, which was completed in 2000.

The Commission’s vision is to restore our Capitol to its original splendor.

Capitol of Light (2010) documents the renovation, remodeling, and expansion of the Capitol, including the addition of the new underground "wings" for senators and representatives.

Exclusive access during construction allowed our cameras to capture the painstaking efforts at restoration of some of the hidden gems of the original building, like Statuary Hall on the 4th floor.

Interviews with architects, contractors, Capitol Commission members, governors and lawmakers provide perspective; while re-enactments bring to life the remarkable John Tourtellotte, who helped create what one critic called "the best of America's capitols."

Actor M.A. Taylor became John Tourtellotte for this production, with the Capitol and the old Carnegie Library providing the backdrop for the re-enactments.

The documentary also explores the rich and colorful history surrounding Idaho's search for a capitol, dating back to events in the 1860's that threatened to split the state asunder.

Known affectionately as "the people's house," Idaho's Capitol building reopened its doors in January, 2010, after a restoration and expansion project that took more than two years and $120 million to complete.

Visitors will see a building that meets all modern safety codes while still retaining the charm and eloquence that the original architects envisioned.

Designed by architects John Tourtellotte and Charles Hummel to be "a beacon for noble ideas," the Capitol's massive sandstone walls and stately dome have withstood a century of use. But inside, the people's house was being asked to do the near impossible: to accommodate 21st century demands while still maintaining its 19th century form.

The actual work on the Capitol building commenced in 1905, under the tutelage of two dissimilar architects, John Tourtellotte and Charles Hummel. Their collaboration produced a building literally flooded with light, where "all the forces of nature are harnessed and made to serve and contribute to the welfare of man in this building."

This singular building reflects the dreams of the generation that built it; and it continues to hold our attention and love today.

You can watch this 42 minute film online at the IdahoPTV video player.

From Capital to Capitol

From Capital to Capitol (2014) chronicles the 1865 move of Idaho's territorial capital from Lewiston to Boise and explores the interplay between the Idaho Territory and the eventual creation of the state of Idaho.

"The transfer of power from Lewiston to Boise can still raise hackles about 'the stealing of the capital,'" explains producer Bruce Reichert. "This is a period of history that is crucial to understanding Idaho's destiny."

The impetus for the 12-minute video segment was the construction in Lewiston of a replica of Idaho's first territorial Capitol, which housed the first and second territorial legislative sessions. The small building, constructed by volunteer labor, was dedicated in Lewiston in July of 2013.

Historians Keith Petersen and Carole Simon-Smolinski help shed light on the conflict that erupted when Boise replaced Lewiston as Idaho's seat of government, and how decisions made 150 years ago still impact the present. Funding for this program was provided by Idaho's Capitol Commission.

You can watch this short documentary online at the IdahoPTV video player.

When IPTV’s “Assassination: Trial of the Century” was completed in the fall of 2007, I told Bruce Reichert that I’d be delighted to work on any future project that could use an historian. In January of 2009, he took me up on that, asking if I would participate in what became “Capitol of Light.”

Like my work with “Assassination,” the new project was a great deal of fun. It was also a very, very different experience in some ways. Most important, the major character in the show wasn’t a radical labor leader or a hired assassin or an attorney or a judge or a detective; it was a building. And the community that Bruce gathered was a good deal more varied: this time, we had a web designer and someone who specialized in school materials–not to mention Gary Daniel, who was liaison between the Idaho Capitol Commission and just about everyone else and who was a faithful and charming attendee at our weekly koffee klatches.

Except for a few minutes (featuring Mark Anthony Taylor as the building’s co-architect, John Tourtellotte), “Capitol of Light” is not a docudrama. It does, however, include a lot of people speaking on camera: governors, lobbyists, legislators, members of the Capitol Commission past and present, the grandson of Charles Hummel–the other co-architect. Our Charles, retired from architectural practice now but with his expertise available to us, came to one coffee gathering and had such a good time that he continued to come. His presence was invaluable and delightful. And he was filmed for the program largely because of his work on a “redo” nearly 30 years ago. Sitting in on many of those interviews was a new experience for me, and I found them fascinating.

My introduction to the whole enterprise was a tour of the building soon after I signed on. With solid-toed shoes that came above my ankles and a hard hat on my head, I (with others and an escort) poked around a building that was unnervingly different from the capitol I’d been in and out of for 42 years. It was as if its skin and flesh were being stripped off and only the bones left. But over the next year, as we worked on the history of the building and its construction, we also watched new flesh and new skin go on those sturdy bones, put there by remarkable craftsmen. I learned a bit about construction; I also learned a bit about the back-and-forth process of decision making in a major public venture.

Not all of that learning relates to the efforts of 2007-2009. One of my responsibilities was to dig out as much as I could of the story of the capitol’s location and construction. Once again my former colleagues at the Idaho State Historical Society were welcoming and very helpful as I worked through boxes of the original Capitol Commission’s papers as well as those of the superintendent of construction, Herbert Quigley. (Several of us would like to see a lot more work done on Quigley, who was a most interesting and very competent character.) Then it was off to the newspapers, primarily Boise’s Idaho Statesman, to find out more about the nitty-gritty of the original project. Projects, really, since the central portion of the capitol was built and occupied before bids were even let on the wings. I learned about outrage at trees being removed; sound familiar? I learned about charges of misfeasance, of bribes and faulty construction; a particularly colorful episode is described in Royce Williams’ essay “Expletive Deleted” elsewhere on this site. I also learned–from both manuscript collections and newspapers–about the progress of the construction itself, decisions that had to be made on the fly, choices of material, equipment bought and then loaned elsewhere when it was not needed at the capitol.

And then there were the photographs. I had learned from a friend, who’d been involved with restoration of the capitol’s exterior after a fire some years ago, that Quigley’s papers contained several remarkable images. Indeed: one shows a car being hoisted by a crane...as its occupants wave at the camera! Other treasures are in the historical society’s collections, including a set of images taken from the upper levels of construction and looking right down at the streets. Those aren’t official photographs; they were taken by Murray Badgeley, who worked for the federal government and lived on the grounds of Fort Boise at the time. Anyone with vertigo or a fear of heights should not look at Badgeley’s pictures.

In the midst of all this, early in the summer of 2009, I suffered a serious injury that kept me completely housebound for six weeks and unable to drive for six months. No more Wednesday-morning coffees–at least not until we worked out a way for my husband to drop me off downtown and one of my colleagues on the project to drive me home in a vehicle I could get into. Trips to the library, with patient and kindly chauffeurs, couldn’t resume until fall either. But “Capitol of Light” didn’t go away, and it did a great deal to preserve my sanity. Thanks to Boise Public Library’s cardholder access to the Statesman on line, I could continue to explore its coverage of construction, controversy, and alleged scandal. And thanks to e-mail I could continue to review and edit various parts of the script. I might not be able to explore continued construction at the capitol or join my colleagues for coffee until near the end of the project, but I was still part of the “Capitol of Light” community. Bruce (in particular) and my other colleagues will never know how deeply grateful I am to them for sticking with me.

When the capitol was rededicated in January of 2010, I was (unavoidably) at a meeting in San Diego. My historian colleagues there didn’t understand at first why I had to be in my hotel room, glued to my laptop screen, to watch live streaming of the ceremonies. Didn’t understand, that is, until they heard my stories of doing “Capitol of Light.”

Essays

...the great white light of conscience must be allowed to shine and by its interior illumination make clear the path of duty...

—John Everett Tourtellotte, Capitol architect, 1913

Light is the signature of Idaho’s Capitol building.

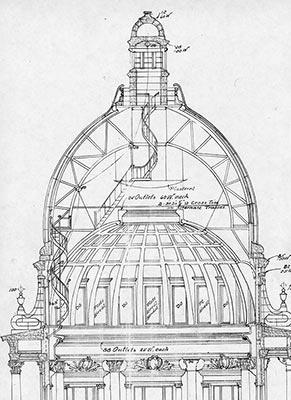

Capturing light, which is nowhere because it is everywhere, posed Tourtellotte’s greatest challenge in the design of the Capitol. The building required the heaviness of stone so that it would remain through time as a singular example of Idahoans’ spirit and enduring commitment to good government. Nothing, however, blocks out light quite as well as stone does.

While Tourtellotte knew that stone would be the best holding pen for light, he knew, too, that light can only be invited in; it cannot be held in any space. Extending every invitation to light, but doing that and keeping the stone’s qualities of strength and endurance must have kept Tourtellotte awake nights.

It is unclear whether or not the answer to this puzzle came to Tourtellotte in a flash or after a long inner struggle between clashing symbols. Some of his writing suggests a long struggle to meld the two concepts. Writing about the ancient architecture of Egypt, Greece and Rome, he saw the love of light and the effects it could create when viewed in outside light, but he had a sour opinion of the inside of these buildings, calling the interiors damp, gloomy, cold, mysterious, even superstitious.

Writing about Idaho’s Capitol at its grand opening, Tourtellotte said the building “is not a cave with ornamental colonnades on the interior standing in superstitious darkness and gloom; neither is it a decorative shell enclosing a gloomy unornamented interior, damp cold and uninviting….

“The interior is flooded with light during the day and at night is ablaze with brilliancy without shadow or dark nooks,” he continues. He made constant references to light, both in terms of making the work that went on inside the building easier to get done and as a symbolic reference to that work being open and clearly visible to the citizens of the state.

When there was some doubt about the appropriation being sufficient to include the cupola atop the Capitol, consultants were called in from east of the Mississippi. They said a good chunk of money could be saved by losing the cupola. But Tourtellotte saw this piece of the construction as the source of what he called “heavenly light.” The arguments and counter arguments are unclear, but obviously Tourtellotte dug in his heels on the cupola, and it still lights the huge rotunda. And white is the dominant color inside the building, almost luring more light, either plain or heavenly. Sky lights on the east and west sides of the Capitol (added in 1920) light the House of Representatives and the State Senate chambers. Most early elected officials working in the building were farmers and ranchers, so they didn’t need a watch. The angle of the light told them when it was time to go to work, to break for lunch, and when to go home for the day.

What the light lights inside the building is very subtle color, mostly used as trim to the white spaces. The color is lit; it never competes with the light. In the compass on the floor of the rotunda is gray marble that matches the Sawtooths, green marble that matches sagebrush, and restricted use of red marble that suggests certain species of salmon.

The exterior of the building takes advantage of free light. It is hard sandstone quarried from Table Rock just east of the Capitol. Its color blends into the foothills behind the building, but is cut to stand out from its surroundings. The stone on the ground floor is cut to resemble log construction in pioneer cabins, then the blocks, quarried by prisoners, climb 208 feet to the golden eagle forever preparing to launch itself from the cupola.

It is hard to pin an architectural style onto Tourtellotte, and he liked it that way. In other buildings he designed before the Capitol — the old Park School in Boise, the Carnegie Library in Boise, Shoshone Episcopal Church, Mackay Episcopal Church, St. John Cathedral in Boise — there is every style from Egyptian to Prairie, sometimes a variety of styles found in a single building. A Gothic arch in a Greek building might suggest a clash of styles, but apparently Tourtellotte found such mixing a challenge. More often than not, he made it work.

Idaho’s Capitol is generally referred to as Beaux Arts (Fine Arts in plain English). But that’s a handy handle. Tourtellotte took full advantage of the plural arts and fitted together whatever architectural styles he considered fine. The fitting together of styles usually had a reasonable and overriding principle that required more attention than a particular style.

In the case of Idaho’s Capitol, that overriding principle is light.

Tourtellotte puts it this way: “(It) is flooded with light. Its rotunda, corridors and interior as a whole is nearer perfect in this respect than any building of its kind perhaps in the world.”

When architect John Everett Tourtellotte took one of his flights of fancy in the design of Idaho’s Capitol, it was his partner Charles F. Hummel who packed his parachute.

Could we have been flies on the wall 100 years ago, a short conversation might have gone this way:

Tourtellotte: “Let’s bust up this east wall over here with a row of windows¸ a kind of Prairie Style approach, that will bring the morning sun right onto the desks in that space…”

Hummel: “Nice, John, but that wall’s got to stand up; it’s got to take wind loads that’ll mostly be coming from the northwest, so it’s got to brace the back wall and you’ve already got that wall full of windows…”

The two men would have used words of their era, but, continuing with the might-have-been, Hummel would be called geeky. Born in Dobel, Baden, Germany, he received his architectural training in Stuttgart, Germany. He spent two years in Switzerland (1876-1878), where he worked as a civil engineer. After finishing technical school, he worked as a draftsman and lived in Freiburg and Renchen, Baden, German. This experience can be squeezed into a single word — precision.

He married Marie Konrad in Renchen in 1882, and three of their six children were born in Germany. Hummel moved to Chicago in 1885, and worked as a carpenter, then moved west to Seattle in 1890. He was working as a draftsman and house builder there and sent for his wife and two sons, Ernest and Frederick C. (A daughter, Julia, died in Germany.) The family moved again to Anacortes and Everett in 1890, where they lived until 1895. Two sons, Frank K and Werner, were born after this move.

The Financial Panic of 1893 that closed all U.S. banks left the family devastated economically. Hummel and his wife were at a pier scraping scallops off one of the piles for supper, when Hummel noticed a flyer lying on the beach. The promotional flyer had been published by the predecessor of the Boise Chamber of Commerce and touted the prospects for success in the Boise Valley because of the boom in irrigated agriculture. The family moved to Boise in 1895, and Hummel went to work that year with the J.E. Tourtellotte Company. Hummel was 38 years old. A daughter, Marie, was born in Boise, but she died as a child.

It is astounding today when architectural drawings are measured by weight rather than page numbers that the original drawings for the Capitol that have been found covered less than 40 pages. And it is somewhat mysterious that Hummel’s name does not appear on any of those pages. If there was a shingle hanging in front of the T.E. Troutellotte & Co. at 215 Overland Building in Boise, Hummel’s name wasn’t added as a partner until 1912. However, he was there and working on the building from the beginning of construction in 1905.

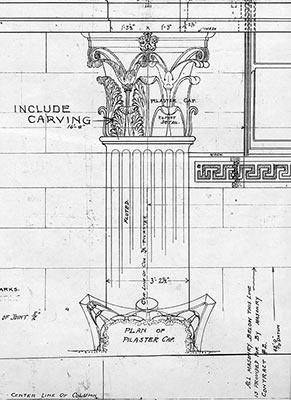

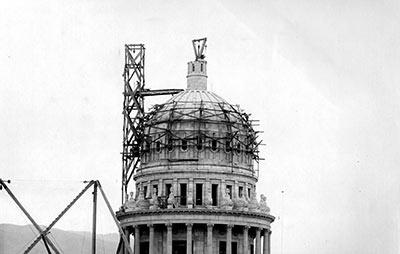

Evidence of Hummel’s work and influence on the building reflect the omission of his name on the plans. His contributions aren’t always obvious. The fact that workers had to dig down 20 feet to river rock before they began pouring a foundation shows Hummel’s attention to detail. His tight calculations set weight limits at the base of all the Corinthian columns around the rotunda. It couldn’t be more than 200 pounds per square inch. His work shows up in the steel specs for the centers of the columns and in the engineering involved in transforming hot springs into winter heat for the building. He was building “green” before green was cool. The soaring dome on the Capitol soars because of Hummel’s precise calculations on the angles and riveting of the web of steel support for it.

Hummel’s specifications for the tensile strength of steel beams gave Superintendent of Construction Herbert E. Quigley a lot of headaches. Suppliers said finding the specified steel was difficult and getting it way out to Idaho was a logistic nightmare. Hummel wouldn’t budge. The result was steel still standing, and Quigley buying the derricks to lift it, hiring workers only when he had the right steel, and putting mumbling factory reps back on the train going east.

The Hummels would stay in Boise, with Charles’ two sons, Frederick and Frank, joining the firm. The Tourtellotte name would leave the shingle, but Hummel Architects PLLC is still listed in the Boise directory at 2785 North Bogus Basin Road. It is possible a Tourtellotte or two could still be in Boise, but if so, they have cellphones.

Tourtellotte and Hummel probably were an excellent team, each one making the other’s dreams a reality and each coming into the dream from a different route.

The Idaho Statehouse as we know it today was the forty-fifth state capitol to be built in the United States. Only five other states have newer capitols—Washington, Oregon, Utah, Alaska, and Hawaii. With so many examples it’s reasonable to look at the origins of our capitol’s shape and style—its design family tree. In that tree there are thirty-five domed state capitols including ours. Among the fifteen without domes there are some whose shape and style are essential to the design of the rest. The significance of all of them, in the estimation of architectural historians, is that skyscrapers and capitols are America’s unique contribution to the monumental architecture of the world. Skyscrapers—which unite structure and function—capitols which function as symbols of democracy.

All of the states have capitols with similar histories beginning with their territorial capitols or colonial statehouses. What distinguished them in colonial times was the need to accommodate a royal governor and one assembly. After the adoption of the Constitution our colonial statehouses were obsolete. Their successors had to accommodate an elected governor and two assemblies. The floor plans for two occupants became floor plans for three. A three-part building form often resulted and was typical for many of the new capitols. The form itself began to be regarded as a symbol of the American system.

But there are important exceptions, particularly the Virginia Capitol built in 1785 with directions sent from France by Thomas Jefferson where he was America’s representative. It is a single rectangle with a gabled front portico supported on six Corinthian columns and a classical cornice. Its model was the Roman temple in Nimes known as the Maison Caree. Jefferson asked that it be called a capitol—not a statehouse like its colonial predecessor in Williamsburg. He was thinking of Rome’s Capitoline Hill, the seat of the ancient Roman Republic, with its connotations of civic duty and heroic virtue. Gabled and columned entry porticos and the decorations of classical Rome became symbols of the ideals of the American Republic. The United States Capitol and virtually every state capitol followed that convention.

The Maryland capitol in Annapolis is another significant exception to capitols with three-part facades. Construction was started by its rambunctious colonial assembly in 1774, two years before the Declaration, and continued building it during the Revolution until its completion in 1779. Its plan is a big square with two assembly rooms flanking a central area for the executive and a large entry and gathering space with stairs leading to the upper floor. The need for daylight in this large interior prompted the builders to construct an impressive octagonal wood tower with many windows above the gathering space and projecting it high above the roof of the second story. The volume and height of the tower’s open interior ringed with second floor balconies created an impressive space and attracted the attention of other designers. The exuberance of its design was completed with the later addition of a small dome topped by an accessible cupola surrounded by a viewing balcony.

The Maryland Capitol was built of brick and wood and it otherwise resembled the Georgian colonial style buildings built prior to the Revolution. The force of that interior space and its potential as a dome influenced the design of other capitols and eventually that of the United States Capitol.

The Massachusetts State House of 1795 was the product of Charles Bullfinch, a Boston aristocrat, who studied in Europe and England where he admired London’s recently constructed Somerset House which continues today as a government building. Prior to landing the Massachusetts commission he designed the Connecticut Capitol in Hartford which impressed the Massachusetts Commission but few of its features were used in Boston.

The plan of the Massachusetts State House is a shallow rectangle entered on the long side up a wide outside stairway to the elevated main floor. A two-story portico extends across half of the entry side. The main floor level of the portico is an arcade supporting an upper level terrace whose flat roof is supported on Corinthian columns. The building walls of the upper floors are smooth finely jointed stone. The masonry walls of the ground floor are rusticated. It is virtually the design of Somerset House.

Bullfinch topped off the Massachusetts State House with a large hemispherical wood dome which rises over a gabled attic set back from the building front. The main house of the Massachusetts legislature sits in grandeur below it. It is not quite as grand as the dome of the Roman Pantheon but the symbolic content is evident.

In 1793 the design of the United States Capitol was awarded to an amateur architect whose work was supervised by three professionals, notably James Hoban, who designed the north wing in a style similar to contemporary English buildings. His design was a three- part plan with matching wings separated by a central rotunda. He was succeeded by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, a fully trained architect, who finished the north wing and started the south wing which was underway when it was destroyed in 1814 by the British in the War of 1812. Restoration was commenced by Latrobe but he resigned after a dispute with President Madison. The restoration and completion of the wings and the central rotunda was completed in 1830 under the direction of Charles Bullfinch. The design for the East Front of the rotunda with a wood dome was essentially that of his Massachusetts State House.

By 1850 it was evident that Congress and the Supreme Court needed more space. Thomas U. Walter was commissioned to design and supervise the addition of new north and south wings and an extension to the west. But Walter’s supreme achievement was the removal of the Bullfinch dome and its replacement in 1861 with the cast iron dome and its cupola with the figure of Liberty. By 1863 the Capitol was essentially completed as we see it today and Walter resigned in 1865.

Well before its final completion the United States Capitol became the great symbol of the Republic. Idaho’s Capitol was bound to be designed in its image. Of course it is considerably smaller than the Washington model but it has been noted that the proportions and details of the dome are closer to those of the national capitol than most of its predecessors. It also inherited the other symbols that came down through the family tree—the decorative details of the Classical Revival, the grand front stairs, the gabled entry portico supported on Corinthian columns.

They are important but the great achievement of its designers is the impact of the rotunda’s space with the soaring interior of the dome and the bright white and muted grays of its marble and scagliola. The Capitol is organized around its superb rotunda and it is truly a celebration of light.

Scagliola (scal-lee-ola) is that thin coating on a column that turns its plain old steel, brick, and concrete innards into the art of human aspirations. It is the evidence of our better selves that resembles marble, thus committing to the ages those dreams our words cannot bridge. It is not the marble of quarries; it is marble made by us, making it somehow more important than the stone.

If you’re interested in making scagliola, you won’t have a lot of competition. It is difficult to make and easy to screw up and takes thousands of man-hours, and just about anything can throw the process awry at any step in the process. It’s basically art from glue, so it’s a sticky mess until it’s done. But when its done right, it takes on that milky sheen, with no glare, that is pleasing to the eye. It draws the eye, in fact, for it suggests geologic magic in dark, hot places far underground where real marble is forged.

Classic scagliola begins with a silk sheet stretched over a marble table. White animal glue is applied, and raw silk threads with knotted ends soaked in earth pigments are pulled through the wet mixture like a string puzzle on a child’s hands. This process gives a final marbling that’s fine-grained, a spider’s-web effect.

For columns like those in the Idaho Capitol, the process is a bit more straightforward. The thin bed of glue-plaster (sometimes a new white cement called Keene cement) is laid down on a canvas—sailcloth or burlap. Then artists are called in, not with brushes but with trowels, and they apply earth pigments swirled with a lot of wrist action.

The art is to get the splotches, swirls, bubbles of marbling into the mix in random shapes, dispersed so that the underlying color isn’t overpowered. Before the mixture sets, it is wrapped around a column—canvas on the outside; smoothed out; and allowed to dry some more. At just the right time, the canvas is peeled away, leaving a somewhat pitted surface that has to be rubbed, sanded in shifts of finer and finer consistency, then polished. The result looks a bit like those old pieces of oilcloth that were used as tablecloths 50 years ago. The Capitol’s scagliola is about 3/32 inch thick.

Yes, there is a seam when panels or the ends of panels join on the column. Never in a thousand years would anyone be lucky enough to get the random pattern on one side to match the pattern on the other side. Again, the artist is called in. The seam is treated like any other crack in a column that needs repairing. A swirl that starts on one side is carried over to the other side. An arabesque that’s missing a “besque” on the other side has to have one painted in. If two white areas collide, the “crack” has to be filled and sanded smooth.

We have looked for seams in the white and sagebrush green of the large columns around the rotunda of Idaho’s Capitol, but we can’t see them. In the current rehab work, other things have been found: gobs of Juicy Fruit chewing gum from maybe the 1950s; nicotine stains perhaps from a 1920s legislator’s cigar; holes punched to hold a poster announcing a public hearing; plain old dirt; tape that held a paper plate telling family members where to meet the rest of the family; peanut butter and jelly from the hands of someone who tried to reach around a column; chipped spots where a dolly got away from somebody; varnish and yellowing shellac….

EverGreene Architectural Arts, whose president and executive project director, Jeff Greene, is a graduate of the Chicago Art Institute, is working on the two basic styles of columns in Idaho’s Capital—Roman Corinthian and Greek—that reflect the original architect’s penchant for mixing styles in buildings he designed. Bases and shafts of both columns are similar, but the styles can be separated by the flared tops, called capitals.

The Corinthian columns around the rotunda and at the front and back entrances have capitals designed to resemble, not potato leaves, but a foliage plant that grows around the Mediterranean. The acanthus leaves are deeply slotted and curved, lending a symmetrical and full flare to the columns. Those in Idaho’s Capitol are the most fluid and complex—the Renaissance style. Corinthian column shafts can be smooth, as are those around the rotunda, or slotted, as they are at the north and south entrances.

Removing old paint (as many as 15 coats of it) from these leaves and filling in the chipped plaster of their construction took days of work with tools as small as toothpicks and nail files to sharp putty knives. Even with plastic gloves, there were some scraped knuckles. To protect themselves from possible old lead paint, the workers resembled surgeons more than painters.

Greek columns are usually smooth, and their capitals are clean, straightforward scrolls. These smaller columns stand in a circle at the back of each of the mezzanines around the central rotunda and can be found in various spaces on each of the building’s four main floors.

If you weren’t asleep in Art Appreciation 101, you know that columns hold up an entablature—a very decorative or very straight-lined grouping of architraves, friezes, dentils, all topped with a cornice. Between the capital and the architrave is a thin, level piece of stone called the abacus. If you took home an A in AA-101, you know that the sky’s the limit on what can decorate entablatures, but the dentils are always what their name suggests: teeth.

EverGreene (out of New York City, Oak Park, Illinois, and Oakland, California) recounts a rich history for scagliola. It has been used for at least 1,500 years; it has been found in Egyptian tombs. The formula was kept secret for centuries, usually available only from very dedicated monks; but the secret leaked out, and it became popular in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries mostly because nature doesn’t make curved marble. And the colors on nature’s palate don’t stretch as far as some have wanted.

The faux marble fad died out, however, and by the 1920s so did many of the artisans who knew the essentials of the intricate work. Starting from a few notes and hints in old correspondence, books, and interviews, Jeff Greene finally figured out, if not the best way, his workable way of making marble as beautiful as or more beautiful than the real thing.

If you take the Idaho Territorial Seal and the Constitution out of a locked safe and put them in a saddlebag, telling only those who agree, then take them from Lewiston to Boise, is that just a move or is it theft?

Back in 1864, representatives from the Northern section of Idaho Territory gnashed teeth, stomped and called it grand theft, even threatened to leave Idaho and join the Washington Territory.

No, said representatives from Southern Idaho, it was just a move that brought the capital to where the people were. The people of the time were gold miners. The gold had played out around Lewiston, and Boise Basin fields were opening, the country around Idaho City being a major one. There was a surge of miners to Southern Idaho after the 1862 discoveries, along with the farmers who started clearing sagebrush around Boise to feed the miners, an Army base, and businessmen setting up shop to sell all of them anything they needed. All of it left the Lewiston area essentially de-peopled.

Since there was no Supreme Court in place at the time to call it either theft or move, and the territorial governor, a New Yorker named Caleb Lyon who was ambivalent about his middle-of-nowhere assignment, was out-of-territory, the arguments raged as only arguments can in a gridlocked and leaderless bevy of politicians.

Depending on where you lived in Idaho, the dastardly deed or official move occurred on March 29, 1865. With Lyon absent, the newest Territorial Secretary (Secretary of State) Clinton DeWitt Smith named himself acting governor. He went to nearby Fort Lapwai, brought a contingent of soldiers to the Lewiston Capitol building, broke into the building, loaded the Territorial Seal and as many official papers that would fit in his saddlebags, and headed to Boise. They were on the road (make that trail) for 16 days, arriving in Boise on April 14. This seems a long time, but the group probably wasn't familiar with the foul weather that can hit in early spring in the high prairies and rugged canyons between the two cities.

Foul! the Northerners cried. But Smith had seen the out-migration of miners as he rode into Lewiston. He had arrived on March 2, 1865.

The Northerners had thought they had a tight grip on the capital. The first territorial governor President Abraham Lincoln had sent west in 1863, a man named William H. Wallace, had picked Lewiston as the capital city. It seemed a good choice. The city at that time was larger than Olympia, Seattle, and Portland put together. It was also the closest Idaho city to his residence in Washington. His temporary territorial secretary, a man named Silas Cochran, appears to have been for keeping the Lewiston site. But a permanent secretary (Smith) can over-rule a temporary one.

How did they get into this knotty mess? Part of it was the dozen territorial governors appointed between territory and statehood. Few of them, it seems, wanted to tackle the enormous problems presented by a corduroy piece of country full of people at odds over almost everything.

It came to a slight head with the first legislative session in December of 1863. More southerners showed up than northerners, and even Wallace must have seen what was coming. It came when the southerners introduced a bill to move the capital to Boise. A representative named H.C. Riggs (a Democrat) introduced the bill, but northerners managed to get the bill tabled at that session, and everybody went home without a decision on where the capital was to be. It wasn't tough to know which site Riggs favored. He had named his son Boise, and he carved Ada County out of Boise County, naming it after his daughter.

But a funny thing happened in that first session. Apparently by mistake, the first session set two dates for the second session - one on November 14, 1864, and another on January 1, 1865.

Everybody showed up on November 14, this time with even more southern representatives. Arguments filled with spit and vitriol replaced debate, but the southerners managed to maneuver the Boise capital bill through the legislative mill. Governor Lyon signed the bill.

Northerners sued. They said that the legislature should have met in January instead of November, and everything passed during the November session was invalid. With no Supreme Court, a Lewiston judge heard the case and upheld the northerners' plea. Probate Judge John G. Berry locked up territorial records and said that if Lyon or Cochran or anyone else tried to remove them, they would be arrested and jailed.

Cochran apparently didn't want to remove them, and Lyon was out-of-territory, so Cochran, after traveling to Washington to talk to Lyon, declared that since Lyon was out of the territory, his signing of the bill was not binding. He refused to lend a hand by opening the safe for troops sent to the capitol by Lyon. Enter Smith, the permanent territorial secretary. He personally oversaw the move-theft on horseback to Boise. Smith had been chased to the Snake River ferry by U.S. Marshal Joseph K. Vincent, who waved Judge Berry’s warrant for Smith’s arrest. While the troops kept the marshal at bay, Smith made it to the ferry, and he didn’t stop until he was across the river and into Washington Territory.

Smith arrived in Boise April 14, 1865, and made a short speech on the balcony of the Overland Hotel. He said he was among friends. A large crowd of Boise residents was there to cheer him.

“I feel welcome now, for it seems to me that I have got among my friends. It is the first time I have felt so since I arrived in the territory,” he said. He said he planned to stay in Boise, then left the balcony after saying he was very tired.

Smith’s arrival in Boise got little press coverage, for he had arrived on the same night President Abraham Lincoln, the man who had appointed him territorial secretary, was shot at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C.

That wasn't the end of the story.

A Supreme Court came into being in 1866, and since the original lawsuit had not been settled at the territorial level, the court finally reconsidered the case and ruled, two to one, that Boise was the one and only capital city. However, the action is recorded only in court minutes. An official opinion was never written.

And Smith did not live to see his actions upheld by the high court. While on an inspection trip to the quartz mines at Rocky Bar, he fell over dead during a game of chess. His obituary in the Walla Walla Statesman said he died August 14, 1865, and was buried on the spot “with the usual manifestation of mourning.”

Any public building, especially one as central, visible and historic as a state capitol, draws controversies like a magnet in a bucket of metal shavings.

The charges and counter-charges play out like a love triangle on a cruise ship. Sometimes there's an obvious smoking gun complete with fingerprints, but more often there's just the prolonged grating sound of axes grinding. And getting to the bottom of one can cost as much or more than the amount claimed to have been misspent. Investigations are never cheap. Any time you announce that you want to build a capitol and you want to do it with human beings, it's like opening a floodgate in the middle of the rainy season.

Anybody who isn't next door to the site is sure it's in the wrong place. Occupied by two, sometimes three, political parties, the site becomes the center of great effort to sway public opinion to and from the party in power. Those who bid on the project - and there were 19 bidding on the Capitol in 1905 - is among the good places to find a sore loser. The best laid plans and designs are bound to miss a few details, and the details that are there can get lost in translation anywhere between the architect and a subcontractor. Make restoration a part of the project, and you can find a spendy or time-eating surprise under every pried plank. The humans who are doing the work or watching it are real people with a plethora of agendas. In other words, the Capitol has been a controversy minefield.

The Motherlode Controversy

His name was John W. Smith, and he was a Boise architect who had bid on the contract to design the Capitol. He wasn't awarded the contract, and his actions following the rejection make him the top-ranking sore loser of the entire project. Only one of his buildings, one that shows he had talent, still stands in Boise at the corner of 8th and Idaho and is called the Fidelity Building. It is not hard to see why there's only one of his buildings still around. What is hard to see is when he would have had time to design any more, being so busy challenging nearly every aspect of the Capitol's construction.

Boise's Capitol News managed to cram most of the charges into an article appearing on October 22, 1912. Apparently without checking into any of the allegations, the paper published Smith's list:

“Grand Jury is probing into alleged scandals in the Capitol Construction.”

Following this headline is a long list including “reckless and unwarranted disbursement of funds, conversion of state property to private use, failure to advertise the bonds for the new state capitol according to the law….

“Now being probed by the Ada County Grand Jury, it is said, (are charges involving) allowing extras with no provisions having been made by law, changes in the terms of the contract and in the specifications unfairly made, alterations in the plans and diagrams authorized without proper protection of the state, and other things having been done by the commission and the architect in direct and positive violation of the express provisions of the contract.”

Then Smith gets personal. “We intend to demand of the (Capitol) commission and the architect what has been done with every cent of money that has been expended, how each and every allowance was made, why the changes in the specifications were allowed, what has become of several thousand feet of lumber that the state bought, what has become of the material and other goods that was bought by the state with no accounting… (W)e charge absolute incompetency and inability on the part of the architect in the management of the construction of the Capitol….”

Named in Smith's barrage were Gov. James H. Hawley, O.V. Allen, state treasurer, D.C. McDougall, attorney general, and John E. Tourtellotte, supervising architect. One allegation made earlier by Smith - that the marble stairs winding up from the first to second floors were insufficient in strength - backfired on him. A widely circulated picture of the same steps loaded with 30,000 pounds of cement took the wind out of that sail.

Grand jury deliberations are not public. If the grand jury did consider any of the charges, there was no mention of it in any of the public indictments announced at the end of its session. Also, the Capital News and The Idaho Statesman were competitive newspapers in Boise, the Statesman being generally supportive of the commission and the construction, with the News looking to scoop its competition.

The State Senate took up the issue, with the Republicans submitting a majority report that exonerated the accused and said other charges were not proved. Democrats had submitted a minority report that said the major charges had been proved by the investigation, and the grand jury should look at them.

The great furniture flap

It's the spring of 1912, and State Treasurer Orien V. Allen, a member of the Capitol Commission, runs a furniture store in Boise called Allen-Wright Furniture Company. His wholesale supplier is Wollaeger Manufacturing Co. of Milwaukee. Wollaeger is chosen among several bidders to supply furniture for the new Capitol. The specs said the state would pay no more than $45,500 for all the chairs, desks, couches, drapes, etc.

Another bidder was one Arthur F. Folts, who ran another furniture store in Boise, one his stationery said sold “furniture worth while.” Folts was quick to say he smelled a rat. In a “letter to the voters of Idaho,” Folts wrote that Allen took advantage of other members of the Commission's Purchasing Committee, men who didn't know the difference between mohair plush and silk plush drapes, selling them on Wollaegers.

Folts' allegations strongly suggested the furniture contract was really with Allen-Wright Furniture, and Wollaegers was just listed as a blind. He said the state was getting second-rate furniture with price tags that didn't say cheap, even though the total reached $45,500, giving somebody about $15,000.

In a letter to architect John E. Tourtellotte, then in Milwaukee checking out the furniture, Construction Supervisor Herbert E. Quigley said there had been one error in the spec sheets given to bidders. He said a circular desk and fewer filing cabinets than needed went to bidders, but this set was later revised to more filing cabinets and a square desk. The error was that Wollaegers did not receive the revised specs with additions. Folts did get the revised specs with additional filing cabinets and a square desk. The square desk saved about $267. His letter doesn't indicate how much extra the additional filing cabinets cost for the Pure Food Inspector, who said he needed them after the first specs were printed.

After Folts circulated his letter, reporters began to ask questions. Allen, worried about what the scandal would do to his bid for another term as state treasurer, convinced the commission chairman that he benefited in no way by the contract with his furniture supplier, said his employees would help in no way with installing anything in the contract, and offered to resign from the commission. Quigley said the error on Page 11 of the specs was being blown out of proportion; they would just have to take their lumps on that one, and should simply negotiate with Wollaegers to get the best they could for the state - furniture that no one would question on quality.

Gov. James H. Hawley must have had his ear to the ground on the issue, for there is a letter to him from Tourtellotte & Hummel telling him what the state was getting. The letter says that after intense negotiations, the total cost of the contract was $35,000, with the state getting some furniture more expensive than the specs called for and some cheaper, but all of it “very excellent in construction and beautiful in appearance.” Wollaegers was described as being cooperative, since the firm was concerned about its business reputation.

“The right has been reserved in the specifications for us to take to pieces any one piece of furniture of each type... if we wish, and the company must stand the expense of replacing the same. This penalty is made more severe by the power of the architects to reject every piece of furniture of the same type if the piece destroyed is not up to specifications,” the letter said.

As Quigley said they would do, any savings in the furniture budget ($10,500 in this case) would be transferred to other budget items nearing or in the red ink category.

Dome-de-Dome-Dome!

No political party can resist the slightest opportunity to advocate saving taxpayer money, and both parties have come to agree that accepting the lowest bid on any public project is the way to go.

While it does save money, the low-bid philosophy has its negative side. For example, a state agency can save money with low bid but can also spend a lot of money training an employee for years, then risk it all by sending that employee to North Idaho in a plane with a low-bid pilot. In recent years, exceptions have been allowed in the bidding process to solve this problem.

However, low-bid was king when the central portion of the Capitol was just off the drafting table and foundations were being poured. There was a rush to get the building done and the legislative sessions into it, and there was a move afoot to save $75,000 at the same time. That was the cost of the dome on the building. Leading the no-dome contingent was a member of the Capitol Commission, Secretary of State Wilfred L. Gifford (later secretary of the commission).

The controversy boiled down to who had the most or the most prominent advisory architects. Tourtellotte found the dome critical to his design around the use of skylights for interior lighting and to give the Capitol the artistic impression of solemn aspirations of good government. Along with Commissioner Orien V. Allen, he traveled to the national Capitol.

The trip was covered this way in the Statesman: “After conference with the supervising architect of the treasury and other eminent eastern architects, they have concluded that the exterior plan of the building shall not be changed in any material respect and the dome will go on as originally planned.”

The next day's edition, however, had Gifford's response to the report: “You may quote me as saying that I am opposed to putting so much money in a portion of the Capitol which is purely ornamental, and which some of the best architects of the country consider poor architecture.

“As to the artistic features of the plan, that I am not qualified to speak of. I do object to spending $140,000 (unclear where this figure comes from) to finish the dome as is now planned and should think that it might be materially cut down from all I can learn and not injure in the least the architectural effect and at the same time save the state a good large sum,” he continued.

If you have driven down State Street or Capitol Boulevard in the last 10 minutes, you can see who won that round. There were some money-saving changes in the original dome design, but they are not readily visible.

Give it elbow room!

The Capitol grounds - too much or too little - have often been discussed, but the issue has never really risen to the controversy level.

Early on, a member of the Nebraska Capitol Commission came to Boise to look at the state's new Capitol. While he liked the building, he thought it should have been farther north, placed on a hill overlooking the city and surrounded by a large park to include plenty of trees for the City of Trees.

The original Capitol Commission had little money to buy land and still have enough to build the Capitol. By using the lot where the Territorial Capitol had stood, they only had to buy one more lot and close one street. In some ways, the smaller grounds fit well. Boise is a walk-about city, and if you need to get to the Capitol in a hurry, you don't have to walk a quarter-mile running into commemorative trees, thorny rose gardens, and muddy petunia beds. Its small size also cut down on grounds-keeping expenses.

More recently, some have lamented the fact that the entire Capitol is visible nowhere on Capitol Boulevard. But the dome and ceremonial south entrance are visible. Buildings along Capitol Boulevard had to be designed for height to function, and the height needed a first floor that took all the space available at ground level. If setbacks had been enforced years ago, the mature trees in the small park in front of the Capitol would still have blocked a full view today.

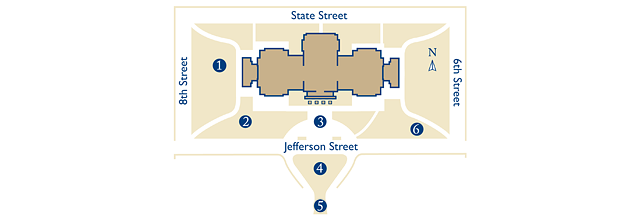

Considerable discussion took place about whether or not to put the expansion above or below ground level. It is difficult to see how an above-ground plan would have worked well. With steps at both ends, the building would have butted against 6th and 8th streets; if the additions had gone higher to give the same space, they would have required entrances behind the House and Senate chambers inside - a design that would have increased traffic around both. And, it is hard to see how the additions could have been designed to prevent them looking like add-on sheds, albeit fancy ones.

The underground additions have skylights over both the main halls and hallways to offices, which keeps Tourtellotte's original and unique use of natural light. There will not, however, be large trees on the east and west sides of the building. The dirt placed over the structure is not deep enough to support anything larger than shrubs. It could be argued that there is a mistake here in the landscaping: the shrubs could have been syringa, the state flower.

If controversies do develop in coming years, they are likely to appear first in the committee assigned to make the impossible decisions about what and where art will go inside the building. Tourtellotte's original design called for white walls with almost nothing on them, better to reflect the natural light coming through the skylights and to make the marble more prominent. The building was designed to be a working capitol. The current renovation, restoration and expansion are carrying that idea into the new century. So, the committee must recognize gifts for display without allowing the building to become a museum or the state's attic.

There have been few controversies like those that plagued the original builders, mostly because citizens have basically understood that a 100-year-old building needs some touch-up work, that the population of the state and the increasing number of legislative bills each year require more people to handle state business, and that the commission early on held meetings around the state to tell people what was happening.

The only taxpayers with room to complain are those who use tobacco products. A tax on these products has paid for the renovation and expansion of the Capitol. The best full view of the Capitol today is from the old Union Pacific Train Station.

Surprise!

Anyone who has ever remodeled an old house knows about surprises. The Capitol reconstruction and renovation is no different. There have been two major surprises in the process that we've discovered so far.

One was the paint used on the walls. Tourtellotte wanted the walls white, very white. They used calcimine paint. It coated nearly every paintable surface. It contained water, zinc oxide and glue and looked like whitewash when it dried. It was cheap and easy to use, so it remained popular until the end of World War II.

But when the painting contractor looked at the walls in the Capitol, he said there was no modern paint that would stick to calcimine. He couldn't guarantee his new paint would stay where he put it. There was only one thing to do: remove the old paint. It took 33 days that nobody could have foreseen. As of the end of May 2009, the reconstruction crews had made up 18 of those lost days.

The other surprise was an earthquake in Alaska. The quake had occurred several years earlier, but it buried a marble quarry under many feet of water - the quarry from which Tourtellotte had specified the red marble he used sparingly for trim in the Capitol. After some delaying searches, a red that was pretty close to the original was finally discovered in a Vermont quarry.

Once upon a time there were ashtrays in the Capitol.

Sounds odd today, since a smoldering cigarette butt anywhere in the building would cause five people to throw their bodies across a smoky tendril rising from a bit of shredded tobacco.

But when the Capitol was closed down for the New Year's holiday in 1992, there was no one to douse a spark left alive on a cigarette. The fire had time to build in the empty Attorney General's offices, and although the entire building had been designed to keep fire at bay, there were carpets, drapes, paper out- and in-baskets, wood desks.

After a security guard noticed the fire late in the afternoon on January 1, he pulled the manual fire alarm (smoke detectors apparently had not worked), and 50 firefighters were called in to douse the flames. The fire was out in about 45 minutes.

Fire, smoke and water damage cost nearly $3.2 million to repair, and the cost could have been greater had the heat from the fire busted the glass walls opening onto the rotunda. It did break windows in the offices, giving the fire the outdoor oxygen it needed to do greater damage. There was smoke and water damage to the second floor offices, some damage, too, for the Joint Finance and Appropriations Committee (JFAC) meeting room (old Supreme Court) upstairs, where the coming year's budget projections were stored.

Part of the repair costs went into a sprinkler system for the Attorney General's Office. Once installed, the system got people thinking about the rest of the building. There weren't sprinkler systems in any other part of the building. The snowball of reconstruction, renovation and expansion of the Capitol started rolling downhill.

Seventeen years later, the work was done, and on November 12, 2009, a certificate of completion was handed to the Chairman of the Capitol Commission Andy Erstad. The things done list was a long one, but near the top of the list was a new sprinkler system for the building, both old and new sections. The only areas in the new Capitol without sprinklers are the rotunda, the senate and house chambers, and the JFAC meeting room. In these areas it was impossible to install piping for sprinklers and keep the historic integrity of the rooms.

But the threat of a major fire played a huge role in the original design of the building in those first years of the 20th Century. John E. Tourtellotte and Charles F. Hummel had designed 190 buildings before the partnership won the Capitol contract. They were working at drafting tables in the old brick Eastman Building on 27 more buildings, including the Capitol, in 1905. Many of these buildings would use materials that weren't fire-friendly.

They didn't need a reminder of destructive fire, but they got one just three years into the construction of the new Capitol, when thick smoke began rolling out of the next-door Central School building. The cause of the fire was unclear, but probably involved faulty wiring in the attic of the 4-story building, being used at the time for temporary state offices and deaf and blind students waiting for a permanent school to be finished. No one was injured that early December morning, but the fire confirmed that sandstone, marble, brick, along with steam heat was the way to go on the Capitol.

The decisions proved correct, for it was 80 years before a reportable fire occurred in the structure. A major reason for that good record was geothermal heat, Idaho's Capitol being the only one in the nation that uses hot water for heat. And the heating system was among the first systems Jacobson Hunt tracked when it took over the Capitol project. Fresh from a major renovation of the Utah Capitol, the heating system in Idaho was a new experience for the company.

They decided to replace the entire system - mechanical, electrical and plumbing. Making that happen, with both wet (hot water) and dry (ventilation), was relatively easy in the tunnels connecting Capitol buildings. But pushing that system through spaces between steel, brick and sandstone... Well, it paid to be skinny.

And none of the work of replacing pipes designed nearly 100 years ago and replaced with just-designed insulated pipes is visible, hidden now behind those mahogany boxes under the large windows or behind those frosted windows that are lit from behind to keep the theme of natural light, so much a part of the original design. Among the maze of pipes behind these windows are completely new plumbing and water pipes, only visible now at a spigot in a bathroom or at a drinking fountain in a hallway.

Another major challenge was the nearly century-old electrical wiring. It had not worked perfectly from the beginning. At the Capitol's grand opening when the outside of the building resembled a Christmas tree as darkness fell, the wiring failed and most of the lights went out. There was a major blackout in the building in 1976, and none of the wiring met modern codes as the 30-month renovation began.

Ninety-three miles of electrical wiring had to be replaced inside the building, and seven miles of feeder line to bring power into the building is new and hidden underground. Stretched end to end, the wire would reach from Boise to Lewiston. Some of it could be threaded through the space between marble and brick and behind molding, plaster and under flooring. Nearly half the wiring had to be threaded through conduit, and some of that required drilling holes in brick walls. There are 43 miles of conduit. All of it - with no wires crossed - made its way to 2,945 light fixtures, 1,205 outlets, 243 light switches.

Wiring, both for electricity and communications, had accumulated over the century, but little of that was removed when new wiring had been added. Every time contractors removed acoustical tile from a ceiling or pried up flooring, they found huge bundles of old, dead wire. Tons of it was recycled before new wiring could be installed, all the work done with lighting coming off generators. All the phone and data lines have been replaced, and wireless Internet is possible throughout portions of the building. It is an indication that communications between government and citizens has moved out of the rotunda and into office computers and cellphones.

But when the new Capitol opens on January 9, not all of the work will be behind walls.

If people look down, they will notice 12,520 yards of new flooring. There will be 43,164 square feet of new marble, mostly in the underground wings. This marble matches very closely the nine different marbles used in the original building. That took quite a bit of searching, according to Project Manager John Emery.

Going back to the original quarry 100 years later, he says, you find the stone today is a mile farther into the quarry than it was when the original marble was bought. That means a slightly richer color and small changes in the graining. There was a special problem with the salmon-colored marble Tourtellotte used for trim. The quarry in Alaska where the original architect ordered the marble is now under over 300 feet of water, the result of an earthquake. But that quarry had put aside some blocks of the red marble, and it was enough to replace trim in the old building. The trim marble in the wings is of a slightly deeper red, but fits because it's never abutted with the original. Only an expert stonemason will notice the difference.

What's certainly visible to any visitor is the mahogany in the building. There are 22,500 linear feet of it in the old building, and 65,933 board feet of it in the new wings.

Tourtellotte had used the dark wood both to direct the eye to office entrances and to contrast with the white walls and light-colored marbles he had used to reflect natural light from the skylights. Much of the mahogany in the original building simply needed to be scraped, sanded and refinished, except for the windows. Installing heavier double-paned glass in these windows would have taken too much time (money), so the windows, the rope and pulley system in each, and the casings were simply bought new as a package. And with modern lighting, along with skylights in the new wings and modern fire prevention, more marble paneling could be used there.

In his original paint specs, Tourtellotte used the word white over and over. Even the metal (fire-resistant) storage cabinets in the basement should be painted with white enamel. He was specific, too, about anything that covered the white spaces. Keep wall-hangings to a minimum, and none at all was best.

But since there was a minimum of color choices available in 1905, the new century painters figured they could get away with two colors - white, of course, but a color called millet (coffee with too much cream), would give the white a lot more punch. It took 3,680 gallons of both colors to get the effect they were after, best illustrated in the ocului in the dome of the rotunda. Here the cream gives the white depth and brings out the intricate patterns in the ceiling.

In this work, and much more, the state has spent $120 million, all of it coming from a tax on tobacco products. That fact should give the 1992 New Year's smokers and the person who dumped an ashtray into what was thought to be a fireproof trashcan room to stop apologizing for an accidental fire.

Had the controversy swirling around Idaho’s Capitol in 1909 been presented on a Greek stage a few centuries earlier, the tragedy would have drawn a standing-room-only crowd.

Fellow minority Democrats in the legislature thought they had the “erratic” Ravenel Macbeth, D-Custer County, under control. He had been relegated to the back bench, where his favorite word - malfeasance - wouldn’t disturb the debates so often.

It didn’t work.

Spending of public money, always holding a high spot on any political top-40, was Macbeth’s pick in late January, when he added “extravagance” to spending on the State Capitol under construction.

He submitted a resolution asking that three senators be appointed to investigate and report to the full Senate. He said the 1905 building fund asked for $350,000 to build the Capitol, that $300,000 had already been spent, that Gov. James H. Brady was asking for $400,000 more, plus $100,000 for the dome, and $1 million to build the wings. The difference between money on hand from the sale of state land and a bond issue, he continued, left the state’s taxpayers, “now overburdened with taxation,” with a $1.5 million bill.

The motion got tabled, but after the session, Macbeth was cornered by Idaho Daily Statesman reporters, who quoted him saying he would “not state at this time what the charges will be, except that wrong-doing will not be among them, although I will bring out some sensational matters.”

The quote guaranteed continued coverage, and ears perked on both sides of the aisle, plus the story garnered public attention. In the next-day reconsideration of the vote to table, Republicans managed to put the question into the lap of the State Affairs Committee, a move Macbeth voted for.

A majority of the senators had voted for the probe, apparently thinking the issue did require looking into, if nothing else to clear the air on Capitol expenditures. But the committee asked Macbeth to provide it with evidence to back up his claims of extravagance on the part of the Capitol Commission.

It was a put up or shut up kind of question, and Macbeth responded by asking for more time to gather evidence, since the commission was late with its financial report, and he stoked the political fire by alleging the State Land Board had leased too cheaply mining land to a Republican supporter (Gaylord W. Thompson of Lewiston) as pay-back for that support. He asked for more time to work on the case. He got five days.

The Idaho Daily Statesman reported it this way:

From the spectators’ viewpoint the session was by far the most interesting of any the senate of the Tenth session has held. When Macbeth touched a match to the pyrotechnics, there were but few spectators in the gallery and in the seats back of the railing, but as the strong sulphuric odor soared through the hall on the second floor, others came in and when the noise that had taken the place of the usual tranquility of the senate chamber died away, the gallery was filled and all back seats occupied.

The next day (Friday, Jan. 30, 1909) Macbeth was still asking for more time while he was adding to the charges. Under the Capitol Commission heading, he added that the taxpayers had lost thousands of dollars from “high salaried expert steel workers loafing around Boise for six months drawing pay when not working, because the commission had not closed its steel contract.” He said he had been told the steelwork in the Capitol “was eight inches out of plumb.” He quoted from the Architectural Review an article he said called the new Capitol “an architectural joke,” and he said the joke was on Idaho taxpayers.

Macbeth also suggested that representatives of the Capitol Commission had taken bribes in awarding construction contracts. He reportedly told the full senate that “the man who put in the lowest bid was refused the contract. When they asked him to ‘put up,’ he said ‘No, I cannot make any money by doing that.’” He also quoted a Moscow newspaper editorial, which said there was an unnamed contractor who said he had been asked for money to bring a contract his way. The paper said it would supply information to the investigation, “so that the truth could be ascertained.”

By now, the Custer County senator was saying he could not get a fair hearing before the State Affairs Committee, because the chairman was a Republican. (In the 10th Session, there were 13 Republicans and 10 Democrats.) Macbeth was a member of the committee on the Democrat side.

There was a lull in the fireworks as the chairman of the Capitol Commission, ex-Governor Frank R. Gooding, wrote to the senate that he would welcome an investigation into both the use of Capitol building funds and the land deals to finance the construction. The Capitol’s construction manager, Herbert Quigley, submitted a report of the outlay of money during 1907-08, which totaled $185,144.

The report said all invoices were in the State Treasurer’s office for anyone to see, and said it was not unusual in a building like the Capitol for on-the-ground expenses to stretch beyond early cost projections. And the Idaho House finished a report on its look into the extravagant spending charge. That report exonerated the commission, but the House said it would put its finding “into cold storage” and wait for the senate committee’s report, releasing both together.

Macbeth, meanwhile, submitted his report to the senate, which included the same numbers he had used in his first resolution. He said the commission’s report had not touched on projected costs of the finished Capitol, so he had no more information than he had already. He called contractors who had submitted bids or expressed an interest in submitting one as witnesses - S.W. Underwood, D.F. Murphy, Joseph Sullivan, Thomas Owens, John Monarch, James Thomas, A.S. Whiteway, and Gov. James H. Brady.

By the middle of February, the State Affairs Committee began three days of hearings that quickly disintegrated into an emotional knock down-drag out fight. Things got hot in a hurry after the first day of hearings in which local contractors expressed personal opinions about things like whether or not steam power was cheaper than electrical, how the commission had saved money on bargain prices for the Table Rock Quarry and land on which the Capitol sat. Architect John E. Toutellotte said the Capitol dome had been cut to one-eighth of its size in his original drawings to save money. And some of Macbeth’s witnesses showed up with attorneys and said nothing, citing the possibility their testimony could be self-incriminating.

The press coverage summarized these sessions in a headline:

NOTHING WRONG WITH CAPITOL COMMISSION

Members and Others Say it Did Work Well and Economically as Could Be

The fireworks erupted during Tourtellotte’s response to the Architectural Review article that quoted a Boston architect as saying the Capitol design was poor design, “an architectural joke.” Tourtellotte was a member of the First Methodist Episcopal Church, the largest congregation in Boise at the time, where he served on the church’s Board of Trustees. So it was a surprise when he reportedly pounded the table and his face turned from red to white as he yelled what newspapers reported:

The man who criticized the building is a rattle-brained... Here, Tourtellotte uttered a coarse name.