IdahoPTV Specials

Please note that this content is no longer being updated. As a result, you may encounter broken links or information that may not be up-to-date. For more information contact us.

Into Africa: The Idaho-Gorongosa Connection

Idahoans love a good comeback story, especially one that involves other Idahoans. Gorongosa National Park, in the African country of Mozambique, is such a story.

Once blessed with thundering herds of wildlife, Gorongosa was ravaged and broken by a brutal civil war that decimated the wildlife and the infrastructure.

The government closed the million acre park—until Idahoan Greg Carr decided to help return Gorongosa to its former glory. A restoration project that big had never been attempted before.

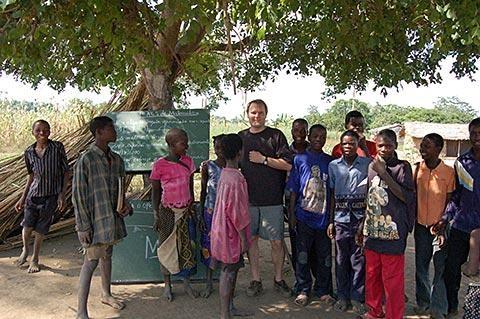

Using $40 million that Carr earned as an entrepreneur, and with a single-minded dedication to his new task, he gathered together a group of Idahoans with unique skills to assist in the restoration of Gorongosa. Working with the government of Mozambique, the team is attempting not only to return the wildlife back to the park, but to help the impoverished villagers who live around the park.

“We’re trying to do something really challenging at Gorongosa National Park," explained Carr. "We’re taking a park that was completely destroyed in a generation of war. Almost all the animals were killed. The people who live next to the park are some of the poorest people in the world. And we’re dedicating a quarter century of our lives, with the government of Mozambique, to try to restore this park. If we succeed, it’s a wonderful model.”

And so far, they seem to be succeeding.

Idaho Public Television explores the Idaho-Gorongosa connection.

Idahoans love a good comeback story, especially one that involves other Idahoans.

Interviews

Greg Carr was born and raised in Idaho Falls, Idaho. As a young man he was quite successful in the tech business; later he founded the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at Harvard University and transitioned from making money to judiciously giving it away. Since 2004 he has been the driving force behind the restoration of Gorongosa National Park in Africa. In that year the government of Mozambique invited him to assist in the management of the park. In 2008, Carr and the government signed a 20 year contract, with Carr bequeathing the park $40 million. Carr now spends about half the year in Gorongosa and half in the U.S.. This has allowed him to continue the task of working with the Mozambique government to make Gorongosa the best park in Africa. In interviews conducted in Africa and in Idaho in 2014, Carr talks about his involvement in Gorongosa National Park.

“We’re trying to do something really challenging at Gorongosa National Park. We’re taking a park that was completely destroyed in a generation of war. Almost all the animals were killed. The people who live next to the park are some of the poorest people in the world. And we’re dedicating a quarter century of our lives, with the government of Mozambique, to try to restore this park, which means bringing back all the animals; but not just that, educating a generation of Mozambicans to be biologists, to be scientists, to be park rangers and tourism professionals and all the different jobs that you need to run a national park. If we succeed, it’s a wonderful model.”

“I went back to the government of Mozambique, and I said: Hey, let’s restore your national park. And when I first said that, I was thinking, this is a great way to create jobs. It’s a great way to create an economic engine in the center of your country. And it was only after I started spending time at Gorongosa did I develop my love and understanding of national parks and conservation. And then I realized, these two objectives fit together, because saving the park will create jobs.”

“The two big objectives that we have here… one is, yes, protect the animals, save the national park. But the other big objective is helping the people who live across the river, helping them with their schools, their health clinics, their farms.”

“There’s something very romantic about Africa, and when you come here you feel different than you do anywhere else in the whole world… and it pulls you away from the stress of your day to day life. And you just think about how magical the earth is, how blessed we are to have such a beautiful earth.”

“In some ways Gorongosa saved me, because I turned 40, and I wasn’t in the mood to start another hi-tech company, even though that had been very fun; and I really didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life. I was a big believer in human rights, but the point is, you want to actually get out and do something. You don’t want to just talk about something. And what Gorongosa did is it gave me a mission for all the rest of the days of my life, and I’ve learned a lot. I’ve made friends. It’s given me an entire philosophy of existence, and I just can’t imagine where I would be if I hadn’t done this.”

“For me to live my life half in Idaho and half here in Gorongosa Park, it was necessary for me to make a connection between the two, so that I can go back and forth and feel at home in both places. So, I’ve invited a lot of my friends from Idaho with different talents to come here; and we ended up with quite a collection of them.”

“There’s 200,000 human beings that live in the ‘buffer zone.’ They’re some of the poorest people in the world. They’re mostly farmers. And we’re engaged in their lives. We build them schools. We build them health clinics. We build them farms. We help them improve their farms. If we help those farmers, we’re helping some of the best people in the world who want to succeed, who need a little bit of assistance; but it’s also good for Gorongosa Park, because if the farmers are doing well outside the park, then they’ll support our objectives of saving animals inside the park.”

“When I first started spending time in Mozambique, it was a real eye-opener, because I would go across the river outside the national park into the community, and these are people who live in houses made of sticks. I mean, there’s no other way to describe it. And they’re people who essentially live with no money that comes into their life all year long. But they obviously had a lot. And what they had was a rich culture, and they care about each other, and they had a community identity. And by and large I would describe them as happy people and quick to laugh. And so there’s a huge lesson in there, really, about what brings happiness.”

“What I love about the people who live around here is they express their views strongly, but they’re always ready to have a laugh. They don’t carry a lot of anger. And Mateus [the park warden] or even I can make them laugh, and we can all agree there’s a problem, what’s the solution, and you can move through a conversation. We Americans could learn something from the way that they can get together as a little village, really express their problems, and then move through them. I don’t know anybody who has a better sense of humor than rural Africans, and it’s a genuine ability to laugh.”

“I’ve been here ten years now, and every time I go across the river I see somebody with a new bicycle, somebody with some new clothes, somebody’s put a new roof on their house, somebody’s planted some new seeds in a garden and got something growing. And I love the fact that they’re able to leverage off of being neighbors of the park and benefit their own lives.”

Steve Burns is the director of Zoo Boise and also in line to be the Chair of the Association of Zoos & Aquariums. After meeting with Greg Carr and visiting Gorongosa National Park, Burns began steering Zoo Boise in the direction of helping wildlife in places like Gorongosa. This has meant a radical shift in the mission of Zoo Boise. In interviews conducted in Africa and in Boise in 2014, Burns talks about how he views the role of zoos in the modern world and what he thinks of working closely with Gorongosa National Park.

“I think right now it’s probably one of the bright spots in Africa, and you can’t say that about a lot of places in Africa. I get strange looks every once in a while, you know, ’Where’s Mozambique? Why gorgonzola? Is it a cheese park?’ No, it’s Gorongosa. It’s a tough word to pronounce and get it in your head, but it’s firmly planted in mine now.”

“I hope that people realize that Zoo Boise has fundamentally changed why we exist. We’re still a nice place to come with the family and have a good time, and it’s still a great place to come and learn about animals, but the most important reason why folks are coming here is because they are actually helping to protect animals in the wild. Every time they come here they’re doing that.”

“We had thought about asking for a donation, and we had done that in the past, and it would generate a little bit of money here and there. But then the thought was: Well, what if we didn’t ask? What if we just charged them for conservation? And so we became the first zoo in the country to charge a conservation fee. So, when you go to the front gate of the zoo, you’ll see that there’s an admission charge plus a conservation fee. It was a quarter when we first started. It’s now 50 cents.”

“In that first year we went from generating about $1,500 a year for conservation to $57,000 a year for conservation, and now we’ve been averaging somewhere between $270,000 and $300,000 a year for conservation. And I think that this is very unique in the zoo world, and so I hope that people in Boise and the state of Idaho really feel good about the fact that their zoo has changed, and we’re sort of out there, you know, helping to lead this effort to reinvent why we have zoos.”

“We’re going to build the Gorongosa exhibit here at Zoo Boise. According to the Julia Davis master plan for the park, the zoo gets five more acres of the park, and we’re going to take our first acre and include it as part of Gorongosa, so it will be our grassy area. And then the area between the zoo fence and the tennis courts will be a fairly large building, about a 6,500-square-foot building, that will house a variety of Gorongosa animals, and so it will be about a two-and-a-half-acre exhibit in all.”

“I personally believe that zoos can be perhaps the largest source of conservation funding in the world. And Zoo Boise is really helping to push that envelope. And this Gorongosa project is going to allow us to continue to do that. We’re changing the reason why we’re building exhibits, because Gorongosa, while it’s a cool place, while you’ll learn about Gorongosa, it also becomes a mechanism to help generate support for wildlife in a place like Africa.”

“I think about animals all the time. I wish I could get them out of my head. It causes me great pain to see what’s happening with so many of the animals that I think about all the time. And so to be able to spend my professional career helping to restore a place like this [Gorongosa], it means so much. There’s times I have to remind myself I can’t save the world, but I have to do something, and this helps keep me from going crazy.”

“This has got to be one of the greatest ecological experiments of all time. To have unfortunately emptied the park of its wildlife, you know, it was tragic the way that it happened; but to now be putting all of the animals back into the park, I don’t know if that scale has ever been attempted before in the world. And so that’s one of the most amazing parts of this park, is science working and unfolding before your eyes.”

Ryan Long is a large mammal ecologist, who specializes in field research on different species of large herbivores like elk and deer in North America and kudu in southern Africa. Long is currently on the faculty of the University of Idaho. These comments were taken from interviews conducted in Africa and Moscow, Idaho, in 2014 and 2015.

“First of all, Gorongosa is a phenomenal opportunity to address a number of the fundamental types of scientific questions that I personally am interested in. There’s opportunities to do things in this part of the world that are just impossible in places that I’ve worked in North America. There’s a lot of interest right now in understanding how populations of large herbivores like antelope are reestablishing, following the end of the civil war back in the 1990s. And there’s very little known about the mechanisms that are driving those patterns of reestablishment. My hope is that we can do a better job of predicting the trajectory of populations of large herbivores here in the park over the next decade or two.”

“I’m interested in the role that termite mounds play in helping browsing antelope make it through the most stressful portion of the year, which is winter. Termite mounds are very large; these mounds tend to have higher concentrations of nutrients that plants like; and they also tend to hold water better than a lot of the surrounding habitat. They maintain trees and shrubs that are really high quality. So they’re very nutritious forage for browsing antelope. So those termite mounds serve as resource hot spots that presumably help antelope make it through the winter.”

“Prior to the civil war you had almost like a miniature Serengeti in Gorongosa, with lots of bulk grazers like zebra and wildebeest and buffalo. Now what you have is very small populations of those bulk grazers that seem to be having difficulty growing for unknown reasons; and instead you have thousands and thousands of midsized antelope, waterbuck and impala. And nobody really has any idea why that’s happening the way it is.”

“The two biggest threats to the continued success of Gorongosa are poaching and human encroachment into the park… the vast majority of the poaching that’s going on is being conducted by people who are extremely poor; they’re bringing in wire snares that they’ve crafted on their own and snaring whatever they can get a hold of and selling that bush meat on the market. That’s a little bit more difficult of a thing to track and put your finger on.”

“Here in the U.S. we have all these nice concepts about things like boundaries, and you say, hey, this is where Yellowstone National Park starts and you can no longer hunt here. It doesn’t necessarily work that way in Africa. It’s difficult for people to wrap their heads around that sometimes.”

“The Gorongosa restoration project has the high quality people that they need to deal with these interacting elements. And I think, although it is going to be a slower process than maybe Greg and others would like, I think it is going to be a process that continues in a positive direction. Ten years from now I expect Gorongosa to be even more amazing than it is right now.”

“It has changed my life in a lot of ways, both professionally and personally. Immersing myself in that different culture and experiencing different world views and different approaches to problem solving has broadened my own perspective of the world. And that is something that I strongly desire to share with others here in Idaho, as a faculty member at the University of Idaho. I hope to initiate field courses at Gorongosa that I could bring undergraduates from the University of Idaho to, for three or four weeks during the course of the summer, so that they can experience research and education on the ground at Gorongosa.”

“It’s important to keep in mind that we live in a very interconnected world, and although it doesn’t always make intuitive sense, things that happen in other parts of the world have lasting impacts on us right here in Idaho. Losing the biodiversity that we have in a place like Gorongosa is not a small thing for anybody in the world.”

Heidi Ware is the Education and Outreach director for the Intermountain Bird Observatory, located on the campus of Boise State University. A trained ornithologist, she visited Gorongosa National Park in 2014 and plans on doing further research in the park. These comments were from an interview conducted in Africa and Boise, Idaho, in 2014 and 2015.

“I do a lot of research on migration of birds in Idaho and also breeding birds, and I’m starting to work with schools to coordinate our outreach efforts to make sure that students see the science that we’re doing. And I think it’s really important, because when I was a kid I didn’t really realize that scientists were like real life people, and so that’s the part that I love about my job, introducing kids to science and seeing that you really can grow up and be a scientist.”

“I met Greg Carr through his niece. He wanted her to meet a female biologist role model. And so I spent most of my time talking to his niece; but I guess I made an impression on Greg, because he emailed me in July and said, ‘Hey, what are you doing in early August? Do you want to go to Gorongosa?’ He’s really excited about the idea of doing education work with IBO, and I think that’s really fun.”

“Boise State’s the only university to offer a Master’s Degree in raptor biology, and so we’re located in this place that has the highest documented breeding density of raptors in the world; a we have this conglomeration of all these bird people that have come together in Boise, which makes working with birds really great, because there’s so much collaboration opportunity.”

“Based on some talking with birdwatchers down there, they think Gorongosa may be the most diverse place for birds in the continent. And when I was there, I was a little overwhelmed. Here in Idaho when I hear a bird call, I know what bird it is. And there I was hearing 20 different bird calls, and I was like, ah, what are all these things? I have no idea. And there’s huge storks just walking right next to your vehicle and birds you can’t even imagine in Idaho.”

“Gorongosa has a big research station there, but because birds are sort of easy to study, they’ve sort of been not studied there. When I was there, we added a couple new species to the park list that we didn’t know occurred in the park, and I was only there for two weeks and am not an expert on African birds. So, I think going back and learning more and more about the birds that are there is only going to benefit Gorongosa.”

“Something I think is really interesting is seeing a niche that would be filled in Boise by, say a hummingbird, here is filled by sunbirds. And so seeing the similarities between the species in how they’re adapted to fill the same role, but they’ve come at it from two completely different directions, I think it’s awesome to see.”

“We got in this helicopter and went up and got to see the huge expansive Gorongosa, and I didn’t realize, you know, it’s almost a million acres. It’s gigantic. And so flying over these herds of animals, watching all the waterbucks scatter as the helicopter went over and getting to see hippos and crocodiles together and just comprehending how gigantic these crocodiles were, I mean, it was amazing. In the flight that we took, we got to see a lion actually attack and kill a little antelope called an oribi, and so watching that as a biologist, I was like: Oh, my gosh! Like, predator and prey, the circle of life! My cheeks were tired at the end of the helicopter ride because I was smiling the whole time I was flying around.”

“But I think a lot of what I’m going to tell folks back in Idaho is about the researchers here, and especially how they’re working with the local community and bringing these kids in. I mean, that’s what I’m most passionate about in Idaho. And I think other faculty at Boise State will probably be pretty excited about that, as well.”

“In the E. O. Wilson lab that’s stationed in Gorongosa, they have a bunch of kids, 16 and 17 years old, that are doing more amazing research than I’ve done. There was a fella talking to us about, you know, ‘I helped describe this new insect species that nobody’s ever discovered before.’ And the opportunities that Gorongosa is giving to those kids in those villages, it’s amazing. And to be a young biologist and see these other young biologists getting to do this, it’s amazing. I love it.”

“I think as far as the Intermountain Bird Observatory goes, our connection with Gorongosa is going to be oriented towards monitoring and research, but also education and outreach, so those are sort of the two main components of what IBO does here in Idaho. And over the past 20 years we’ve really developed this system where we can do research and get scientific value from it, but add this component of education that reaches out to the local community. I think in Idaho that’s important, and in Mozambique I think it’s even more important.”

Bob Poole is a cinematographer from Ketchum, Idaho, who has spent many years in Africa filming for National Geographic. For the past two years he has been working on a television series for PBS and National Geographic International, on the restoration of Gorongosa National Park. He will serve as the on-camera host for the series, scheduled to air in the fall of 2015 on PBS. These comments were taken from an interview conducted in Africa in 2014.

“I grew up in Kenya. My parents were with the Peace Corps originally and then into wildlife conservation, so I grew up sort of with one foot in Africa and one foot in the states. That’s why I still have an American accent. I went to school in Montana, and not long after that I moved to Idaho, where I still live today.”

“I think a lot of us from Idaho really enjoy the outdoors. We love camping. We love the mountains. Here we don’t have the mountains, but we have forests and savannas and beautiful lakes and rivers like in Idaho, and we just enjoy being outside and, you know, being with all the wildlife. We have a lot of kudu that are like elk and impala that are like deer. We have lions, similar to our mountain lions. And the bird life here is incredible, just like at home, only more so.”

“I first came to Gorongosa in 2006 to make a film for National Geographic called “Africa’s Lost Eden,” and that project led me to several other films. I fell in love with this place immediately, worked on some other films, including “War Elephants,” which was also a National Geographic project about the elephants here in Gorongosa. “War Elephants” really helped get this project off the ground, which is a six-part series for PBS and National Geographic International. It basically follows all the work that’s being done to try and bring this national park back to its former glory. There’s a lot of progress that’s been made since I first came here in 2006. We really have a ton of momentum. There’s been some setbacks, but I think things are really going well right now.”

“My role has been as cameraman primarily, but I’m also sort of the main character in this series, and what I do is I work with the lion project, I work with the elephant project, the crocodile project and the rangers; and I just kind of thread all these different little projects together that make up the Gorongosa restoration project. So, it’s a really great role, because I get to be involved in everything, and I really love that.”

“When I first came here, which was two years after the project started, you could barely see a baboon or a warthog in a morning’s drive. Now it’s just like, man, it’s just wildlife everywhere, and it’s getting more all the time... I’m involved in this project because I really love being part of it, and I think that this is one of the most amazing projects probably on the planet. In Africa, you know, you see so much of the wildness disappearing. It’s nice to be able to put some of it back. To work on a project that is designed to help those animals get a good strong foothold again here is really great. It’s a great thing to be a part of. I love it.”

“I think we’re very, very lucky in Idaho, and I’ve traveled all over the world. We’re very lucky to have large chunks of wild space around us. Here in Mozambique there is a lot of wild space, too, but it’s disappearing at an alarming rate. You can go out to the boundaries of this park and see that it’s disappearing. You know, what they call the “buffer zone” is being converted from wilderness into places where there’s no more trees and what was once wild now is farmland. The future of wilderness in Africa seems more tentative than it does at home. And I think that it’s important that vast chunks of this continent still remain wilderness. And being part of this project trying to help make that happen is nice. It makes me feel good, and it’s a nice addition to my career as a filmmaker.”

Katherine Jones is a photo journalist for the Idaho Statesman, the state’s largest newspaper. She visited Gorongosa National Park in the summer of 2014, to write stories about the Idaho connection and about how the Zoo Boise dollars were being spent. These comments are from a February 2015 interview in Boise.

“The cool thing about Gorongosa was how familiar it did seem. So when we’d go on safari driving through the trees, the trees seemed familiar like a Sunday afternoon drive; but you could go around the corner and see a lion or an elephant; I mean, not at all anything like I’d see in Idaho, but it seemed familiar.”

“One of the cool things about the work that Greg is doing is that it’s not just about the animals; it’s also about the people who live around the park that are going to support the animals in the park. We visited the clinic that the Restoration Project has built; and right next door was the water hole that they had put in because it was unsafe to get water out of the river because of the crocodiles. And then we visited the school and talked to the teachers about their needs. And then we visited Mr. Balthazar on his model farm, and that was probably the coolest thing. Mr. Balthazar is a respected elder in the community, and he has taken it upon himself to care for nearly 100 orphaned children; and so the Restoration Project was working with him on how to grow more food differently year around.”

“We were driving along one evening, and all of a sudden, Whoosh, like what was that? The driver screeched to a stop, and it was this gray blob with pink around the edges. It was a hippo come flying out of the woods into the river! I didn’t know hippos could move that fast. Who knew? And so we came to an appropriate place to stop and pulled over, and we kind of walked down to the river… I like to say, guess what I did one evening? I watched a hippo all evening long, just swimming and splashing.”

“I have always wanted to see a cat in the wild… and we were cruising along the road one evening, and the grasses parted and there she was. She was just sitting there staring, and I did kind of an un-politically correct thing and yelled, A Lion! So we stopped and we watched her; and she just sat there and we’d take pictures; and then she got up and she walked off, and we could just see the little tip of her tail flicking in the grasses tempting me. And I thought, I can die happy.”

“We had seen a couple elephants here and a couple elephants there… and then we saw a herd of 20 elephants and I thought, boy this is starting to be something real… And then as we were watching them, we kind of scanned the horizon and then there were more elephants and then there were more elephants all lining this field. And we counted them and there were about 70 elephants. I’m like, okay this is Africa!”

“And then Steve Burns starts talking, and he goes, you know there are 35,000 elephants poached every year, and it’s like 96 every day; so we did some math and those elephants are like 16 hours and 45 minutes worth of poaching. And that, that really affected me a lot. I mean, these are my elephants; these are our elephants. And it really brought home the threat to the elephant population in the world.“

“Life is different after you see elephants and lionesses in the wild; and I’m not really sure how it’s different; maybe it’s bigger; maybe it’s smaller. And it’s easy to forget, so trying to figure out how to keep that alive and that connection is kind of cool to be able to tell these stories.”

Producer's Notes

It's true, we all love a good comeback story. And on March 4, we profile an excellent one, 10,000 miles away. It's not in Idaho, but it definitely has an Idaho connection. In fact, without Idahoans, it's doubtful this international comeback story would ever have occurred.

It all starts with Idaho native Greg Carr, a guy who made his money in the 1980's, in the high tech business, and now uses his millions to promote good causes. A chance encounter with the President of Mozambique – and a National Geographic magazine article — introduced him to a really cool national park in Africa that had been destroyed by years of civil war. Almost all the animals, killed. All the infrastructure, destroyed.

After further discussions with officials in Mozambique, Carr decided to put up $40 million of his own money, to try to restore Gorongosa National Park. Nothing on this scale had ever been attempted before. But Carr is not only helping to restore the park; he's also helping some of the poorest people on the planet, who live around the park. Without buy-in from those villagers, a restored Gorongosa will ultimately fail. Call it human rights, with a twist.

You've got to admire the man. He could have lived the life of luxury with all the wealth he accumulated in his early years. Instead, he chose to live in a tent for his first year in the park, with no running water, and cooking food around a campfire. Greg is someone driven by a strong desire to improve the world, and the planet is the better for it.

But he doesn't just throw money at something and leave. No, Carr has been right there on the ground the entire time, working and defending and cajoling and strategizing to get Gorongosa National Park back on its feet.

And if anyone can do it, it's Greg Carr. There's no ego here, folks. You only have to talk with him for a few minutes to realize his commitment.

This was a different kind of story to tell for director/editor Pat Metzler and me. Neither one of us has been to Gorongosa National Park. So, except for the interviews conducted in Idaho, we shot none of the footage; we were relying entirely upon the generosity of others. There have been dozens of email discussions early in the morning with folks in Amsterdam, where the PBS series on Gorongosa is being edited. That's right, there will be a six part PBS show on Gorongosa airing this fall.

For me, it essentially meant writing the story before seeing the video, something no one ever wants to do in this business. And it meant re-writing parts of the story, once the video arrived.

It affected how Pat approached the editing, too. He first tackled the material we knew we weren't going to get any more footage for... like Intermountain Bird Observatory's Heidi Ware in a helicopter; or U of Idaho researcher Ryan Long with a tranquilized kudu antelope; or Zoo Boise director Steve Burns on a safari looking for lions.

Greg Carr told our Marcia Franklin in an interview that he spent part of his growing-up years hiking in Idaho and Yellowstone National Park, and that he watches Outdoor Idaho whenever possible. “I'm a huge fan,” he said. “It just makes me love nature. And I think that helping people to love nature is part of conservation. Making these films is critical to the heart of our mission. And that's why we reached out to PBS and said, Hey, come on.”

We wish Greg and company the very best as they share their beloved Gorongosa with the world this fall. And, for our part, we are honored to share the unique “Idaho Connection” with our Idaho viewers.

This really should make us all proud.

Links