IdahoPTV Specials

Please note that this content is no longer being updated. As a result, you may encounter broken links or information that may not be up-to-date. For more information contact us.

All Aboard: A Northwest Rail Journey

The history of Idaho and the West was written on ribbons of steel.

Today the passenger trains that once flooded the West with immigrants have taken a back seat to cars and planes.

Yet, it is still possible to view Idaho and the Northwest by rail, to revel in the history and scenery of places like Glacier and Yellowstone National Parks, to feel the power and the speed and the glamour that once transfixed an entire nation.

Idaho History

Call it greed or “manifest destiny,” but in the 1800s, when our nation looked west, it saw its future. The western territories held the promise of indescribable treasures—minerals, timber, land—and the railroads were the key.

But Idaho’s geology was a railroad baron’s nightmare, with peaks and valleys everywhere, and few straight lines.

And yet to get to Seattle, Portland and Tacoma from Chicago and places east, trains eventually had to pass through Idaho. It wasn’t easy and it wasn’t cheap.

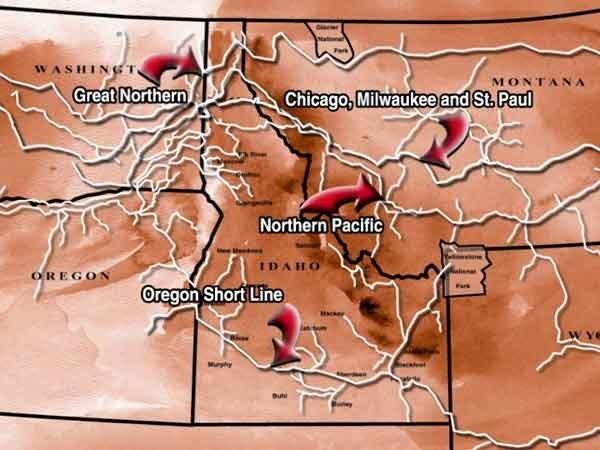

By 1916, four railroads had succeeded in traversing Idaho east and west: the Northern Pacific; the Oregon Short Line, a subsidiary of the Union Pacific; the Great Northern; and the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul.

In fact, early in this century, the Pacific Northwest was a jumble of competing railroads, with close to 3,000 miles of track in Idaho alone.

North Idaho’s virgin forests helped defray the costs of building the railroad through Idaho. In fact, the U.S. Congress offered railroads land along the tracks, much of it timbered land, to encourage transcontinental railroads. The Northern Pacific Railroad received the largest land grant of all.

The railroads themselves were one of the biggest customers for timber. It took 2600 railroad ties for each mile of track. Railroads also needed big timbers for their bridges and trestles.

But the railroads did more than carry goods like timber and grain to distant markets. They also brought emigrants seeking their fortune into the West. Before trains, it could take six months to get from Omaha, Nebraska to Portland, Oregon, via wagon train. After 1884 the journey could be completed in less than six days!

In 1883, a train brought the first tourists to northern Idaho. The tourists had a lovely boat trip around Lake Pend Oreille, and the reporters of the day wrote glowing accounts of the tourist potential around Idaho’s largest lake.

Railroads quickly realized the value of tourism to their business; they created an image of the West as a land of opportunity, and thousands of easterners headed to the land of milk and honey.

Whenever possible, railroads entered the frontier alongside the banks of waterways, because it was almost always the least costly route. However, some of Idaho’s rivers proved too much, even for the railroad barons.

The sheer ruggedness of the Snake River in Hells Canyon, along the Idaho-Oregon border, kept a north-south route through Idaho a mere dream. And the river that turned back Lewis and Clark, central Idaho’s Salmon River, kept railroad builders at bay as well.

Even today, there are no railroads that connect Idaho north and south.

It is hard for us to imagine the power that railroads exerted on the American psyche. Before, trains, each city had its own concept of time, and a journey across America required a person to adjust his watch at least twenty times. “They come and go with such regularity and precision,” noted Henry David Thoreau, “and their whistle can be heard so far off, that farmers set their clocks by them, and thus one well-regulated institution regulates the whole country.”

Travel through the Northwest on rail lines once closed to passenger service.

We explore our fascination with trains.

Rail in Idaho

For seventeen years, this steam locomotive rolled along Southern Pacific tracks before its retirement in 1958. Then in the mid-seventies, the 4449 was restored to help celebrate the nation’s bi-centennial. Since then the engine has been used in movies and for numerous special events.

It was a special event that brought the 4449 to northern Idaho in the summer of 2000. The Burlington Northern & Sante Fe was sponsoring an employee appreciation excursion throughout the northwest.

According to engineer Doyle McCormack, operating one of these trains is like playing a fine musical instrument. “The steam engine is really a magnificent piece of machinery. It’s probably man’s most perfect machine.”

Steam locomotives got their start in the 1830’s, and dominated the railroad landscape for more than a century. In the 1950’s, the more efficient diesel trains began operating, and eventually led to the demise of steam engines. That makes the 4449 a great link to our past.

This popular train runs from Sandpoint, Idaho, to Livingston, Montana. It’s a journey that takes passengers along hundreds of miles of the historic main line of the Northern Pacific Railroad.

The distinctive blue engines of Montana Rail Link power the train from the shores of Lake Pend Oreille to the mountains of Montana.

While the Northern Pacific line was completed more than a century ago, most of the rail cars are from the 1950’s, during the heyday of luxurious rail travel.

The scenery and the history along the route help attract scores of people to this excursion train. Passengers can follow the path emblazoned by Lewis & Clark, and, later, Captain John Bozeman.

At the turn of the century, the Northern Pacific Railroad pushed Yellowstone National Park as a major tourist destination. The railroad built a fifty mile branch line from Livingston to Gardner, Montana, at the national park boundary, and during the summer took passengers to the park.

The Camas Prairie Railroad is sometimes called “the railroad on stilts.” In one five mile stretch, there are more than a dozen trestles, some of the highest in North America.

This railroad is a remnant of the great railroad wars earlier in the century, when the Harrimans and the Hills were fighting over this whole inland area to see who could get the most rails into the Pacific Northwest. They called it “the war” and the Camas Prairie was the result of that war. In the end, the railroads cooperated to build the Camas Prairie Railroad.

This legendary railroad is also one of the few places that allow motor cars on its tracks. By adopting strict safety rules, buying multi-million dollar insurance policies, and paying their way, rail car operators convinced the railroads that they were serious.

As one rail car operator put it, “we’re operating our own trains; we’re operating over this fantastic engineered railroad in some of the most beautiful country around. What more do you want?”

Rail cars weren’t the only form of transportation for rail workers. Some used rail bikes: bicycles that had been modified to run on railroad tracks. By 1900, at least two dozen types of rail bikes had been patented. Today it is still possible to find folks with their own form of “rail cycle” operating around northern Idaho.

When James Hill set about to build the last of the transcontinental railroads, public sentiment had already turned against the robber barons. So the “Empire Builder,” as Hill was known, built his railroad entirely with private money.

Hill was determined to make his railroad efficient, so he sent out explorers to find the lost Marias Pass, mentioned in the Journals of Lewis & Clark. It’s the lowest pass crossing the Rocky Mountains. The lowest possible grade, with the fewest curves, gave Hill a competitive advantage.

The tracks of the Great Northern skirt what eventually became Glacier National Park. James Hill and his son Lewis lobbied Congress to create the national park. In 1910 President Taft made it official, and for the next seven years the Great Northern spent one and a half million dollars building lodges, chalets and tent camps in the Park. To many people, the Great Northern Railway became intertwined with Glacier National Park.

Passenger trains have remained a fixture in the Glacier landscape, even with automobile traffic and consolidation of the Great Northern into the Burlington Northern & Sante Fe. Twice daily, sleek new Amtrak trains wind their way through the countryside.

The train, known as the “Empire Builder,” follows the historic route of the Great Northern, along the edge of the park. For many miles the tracks actually form the park’s southern boundary.

From West Glacier, the “Empire Builder” climbs toward the continental divide, along the Flathead River, past historic waysides like Essex and Java, toward the 5,200 foot Marias Pass. From the mile high pass, the train then begins its long descent to the East Glacier station, a prime jumping off spot for the national park.

Glacier is the only national park on the main line of a transcontinental railroad. The wonderful vantage points, the stunning mountain backdrops, the sheer number and variety of trains all combine to make this an irresistible place for train buffs.

For much of the twentieth century, if you wanted to travel from coast to coast, you took the train. And one of the most luxurious passenger lines was the Milwaukee Road’s Olympian Hiawatha. From Chicago to Seattle, the Hiawatha carried passengers in comfort and style.

Going through northern Idaho, trains negotiated mile after mile of switchbacks and tunnels. It was by far the most expensive railroad ever built at the time. Original estimates put the cost of building the line at $2 million. When it was completed in 1910, the actual cost was $250 million. Idaho’s geology required the route to wind around valleys, through tunnels and over trestles -- the tallest more than two hundred feet high.

But today mountain bikes, not trains, cross the trestles.

Twenty years after the Milwaukee Road went bankrupt, the U.S. Forest Service reopened the route of the Hiawatha, for bike riders. Everything that made the route attractive for trains -- the gentle slope, the scenery, the history -- make it equally attractive for bicycles.

The two percent grade makes it enjoyable for even first time bikers.

The trestles and the tunnels make the route of the Hiawatha memorable. In thirteen miles, bikers ride over seven trestles and through nine tunnels. “It’s just quite an experience to be riding out there in the middle of nowhere,” says Hiawatha trail marshall Dave Leeds.

“You can have hawks circling right beside you. When you stop and look over the railing, it’s a couple hundred feet down to the ground.”

The Hiawatha Rail-Trail can be accessed via Wallace or St. Maries, Idaho or from Montana via the Taft exit off Interstate 90. Complete instructions can be found at Idaho Panhandle National Forests - Hiawatha Trail

While no railroad ever connected Idaho north and south, at the turn of the century, the plaintive whistle of steam locomotives could be heard all through the timbered mountains of central Idaho.

Locomotives known as Shays followed steep grades and rough tracks into places like the Boise Basin, logging Grimes Creek and Centerville and Idaho City. At the same time, the Idaho Northern Railway, and later the Oregon Short Line, began building tracks along Idaho’s Payette River.

By 1914, it was possible to board a train in Nampa, Idaho, and travel all the way to McCall and back. But passenger service halted in 1949, and some of the track was abandoned.

But in 1998, an arrangement with the Idaho Northern Pacific Railroad allowed the Thunder Mountain Line to begin operating an excursion rail line between Cascade, Idaho, and Smith’s Ferry.

The two and a half hour round trip excursion parallels the Payette River and Idaho’s north south highway. Yet there are some sights that only the train provides, like going through the shortest solid rock railroad tunnel in the nation.

There’s one more thing that Thunder Mountain has that sets it apart: a chance for passengers to raft the Class Three rapids of the Payette River. The rail line has made arrangements with a local outfitter, Idaho Whitewater Unlimited, to haul rafts on the train. At the designated put-in, the train stops, the rafts are unloaded, and train passengers exchange their train seat for a place on a whitewater raft.

Many of those who work on the Thunder Mountain Line are volunteers, who enjoy trains and hope to keep alive the railroad tradition. “It’s a disappearing heritage,” says one volunteer, Don Dopf. “Most of these towns in this part of Idaho wouldn’t be here if the railroads hadn’t come first. Just in our immediate area, hundreds of miles of tracks have been taken out in the last twenty years. If there’s any way to help preserve this line by having the Thunder Mountain Line here, I want to be a part of that.”